Superbugs – or to give them their correct name, antibiotic resistant bacteria – arise on repeated exposure to antibiotics.

In any population of bacteria there will be a few that are antibiotic resistant (approximately 1 in 100 million bacteria). If these bacteria are allowed to grow and multiply, an antibiotic resistant infection results.

That is why it is so important to take the complete course of antibiotics if they are prescribed. This is also why we need to be very cautious prescribing antibiotics so that the chances of resistance arising is kept as low as possible.

What is meant by the term “antibiotic resistance breakers” and what potential do they have for tackling superbugs?

Antibiotic Resistance Breakers (ARBs) are molecules that in themselves do not kill bacteria but when administered together with an antibiotic can overcome antibiotic resistance.

Antibiotic Research UK (ANTRUK) is about to embark on a research programme to examine the complete pharmacopoeia and GRAS (Generally Recognised as Safe) library. These numbers equate to approximately 1600 different compounds.

There is evidence in the scientific literature that it is possible to break antibiotic resistance with an ARB, but this will be the first systematic approach to screen the whole library against the most common antibiotic classes and Gram-negative bacteria.

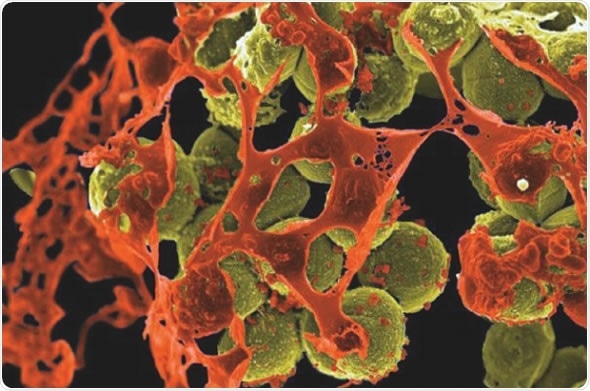

Gram-negatives are responsible for a variety of infections such urinary tract infections, blood and skin infections, pneumonia and sepsis, which are the most difficult to treat with antibiotics owing to these bacteria having a protective outer cell wall that is relatively impermeable.

Gram-negative bacteria are also the ones that are becoming increasingly antibiotic resistant and can lead to serious illnesses or death of the infected person.

One attraction of using existing drugs is that if an ARB(s) is identified, the amount of safety testing will be reduced compared with a novel molecule.

Is the technique similar to drug repurposing?

Basically, the answer is yes. We are examining existing drugs used for any therapeutic purpose for their ARB activity.

In addition, we will be examining nutraceuticals (molecule(s) found in any food that has a health benefit) such as curcumin (a component of turmeric) for ARB activity.

Can you please outline the research study Antibiotic Research UK (ANTRUK) has commissioned to screen antibiotic resistance breakers?

ANTRUK is in the process of identifying laboratories with the capability of testing the approximately 1600 molecules outlined above. Screening will involve high throughput liquid handling, in which the potential ARB, antibiotic and test antibiotic resistant bacteria will be mixed together to determine if any ARB breaks resistance.

Bacterial cell growth will be the determinant of an effect. Concentrations of ARB and antibiotic will be decided from their known therapeutic concentration.

Why will the research focus on antibiotic resistance in Gram-negative bacteria?

Owing to their relatively impermeable cell wall, Gram-negative bacteria are the hardest to find new antibiotics for. This type of bacteria is also the one where the incidence of resistance is increasing.

Species to be tested will be E.coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Acinetobacter baumanii.

Why is this only a short-term solution and what needs to be done to tackle antibiotic resistance in the long term?

Finding ARBs is likely to be a quicker and cheaper process than developing a new antibiotic from scratch. The latter could take 10-15 years and cost upwards of $1 billion whereas finding an ARB might take up to five years and cost less than $50 million.

It is highly probable that, if an ARB is found, resistance would eventually arise. If this happens, then further ARBs would need to be developed.

How do ANTRUK plan to reverse the decline in antibiotic drug development?

As a small charity, we can only research a few of our ideas. Our research programmes have been devised by the Charity’s Scientific and Technical Advisory Committee (STAC) whose members have a wealth of experience and expertise in antibiotic drug development.

Our screening approach based on bacterial cell growth is simple and untargeted – it is empirical and not predicated by any specific mechanism.

What are the main challenges that need to be overcome?

The main challenges for ANTRUK are primarily a lack of funding. As a new charity we have raised close to £400,000 since the Charity’s formation. Our target is to raise up to £30 million in the next 5-7 years but we need help from Government, large charities such as the Wellcome Trust, and the general public. We are always looking for people to assist us whether this be through volunteering, fundraising or forming local groups.

Over what time period do you think we can realistically expect to see the development of new antibiotic therapies? Will this be soon enough?

New antibiotic therapies typically take 10-15 years to develop at cost of upwards of $1 billion. This is extremely concerning since the problem of antibiotic resistance is here and now.

Lord Jim O’Neill, who chairs the Antimicrobial Review, states that if no new antibiotics are found by 2050, up to 10 million people per annum will die from an antibiotic resistant infection.

Whilst 2050 seems a long way from today, it is just two complete cycles of drug development. We need to do more and now.

The Charity believes that seeking ARBs might be able to reduce drug development times. The Charity also has other ideas that it wishes to explore such as combination antibiotic therapy.

Where can readers find more information?

About Professor Colin Garner

Professor Colin Garner is the Founder and Chief Executive of Antibiotic Research UK. He has a scientific background in pharmacology / toxicology and spent most of his professional career at the University of York directing a cancer research lab.

Professor Colin Garner is the Founder and Chief Executive of Antibiotic Research UK. He has a scientific background in pharmacology / toxicology and spent most of his professional career at the University of York directing a cancer research lab.

Besides his academic career he set up three University of York spin-out companies arising from his research which all provided services to the pharma and biotech industry. These ranged from the first independent company in the world to provide genetox services, to an antibody diagnostics company and a company that pioneered human Phase 0 studies.

He founded the journal Carcinogenesis and was a co-founder of a local cancer charity, York Against Cancer. He has published over 220 scientific publications, written 30 book chapters and edited three books.