Researchers have developed an electrical device that has helped a quadriplegic man to move his hand, wrist and several fingers, enabling him to carry out basic movements such as picking up a bottle and pouring a glass of water.

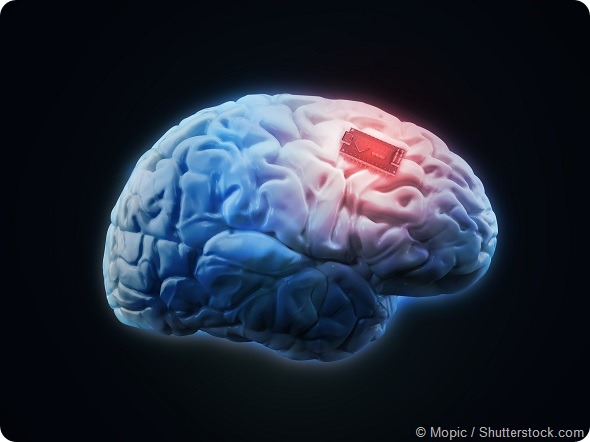

The device is a brain implant that works by picking up the man’s thoughts and transmitting them to a computer, which then decodes the thoughts and sends electrical signals to a sleeve of electrodes worn on his forearm. The sleeve then stimulates his muscles and enables him to carry out movements.

The nerve bypass: how to move a paralysed hand

Ian Burkhart, who is now 24, became paralyzed at the age of 19 when he broke his neck after diving into a shallow wave. The severe injury to his spinal cord meant he lost the use of his legs and forearms.

In a person who is not paralyzed, signals travel down the spinal cord from the brain to reach nerves that are connected to muscles in various parts of the body, which makes them move. In the case of paralysis, these signals still occur in the brain, but the spinal cord damage means the signals fail to be transmitted to muscles.

As reported in the journal Nature, researchers led by Chad Bouton (Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, New York) took functional magnetic resonance imaging scans of Burkhart’s brain while he tried to copy hand movements shown to him in a video. This enabled them to locate the exact area of the motor cortex (the brain area responsible for movement) that was linked to the movements. They then implanted a flexible chip that identifies the pattern of electrical activity that occurs when Burkhart thinks about movement. This information is relayed to a computer, which translates the signals into electrical messages that are transmitted to a sleeve on Burkhart’s forearm. The sleeve, which contains 130 electrodes, transmits electrical impulses to his muscles, essentially bypassing the spinal cord and enabling the muscles to contract.

Human brain implant concept illustration

Basically, the device enables Burkhart to carry out movements simply by “mastering his thoughts,” explains neurosurgeon Ali Rezai from the Wexner Medical Center at Ohio State university, where Burkhart was treated.

The first day we hooked it up I was able to get movement, and open and close my hand,” says Burkhart.

Since then, Burkhart has been attending training sessions every week and can now move several fingers and make six different wrist and hand movements.

The researchers hope that as well as helping people with paralysis, one day the technology could be used to help people who have lost movement as a result of stroke or traumatic brain injury.

Sources