Otosclerosis is a common cause of hearing loss, particularly amongst young adults. It normally starts in their 20s or 30s and it affects about 1 in 200 hundred people. In the UK, about 300,000 people are affected by the condition.

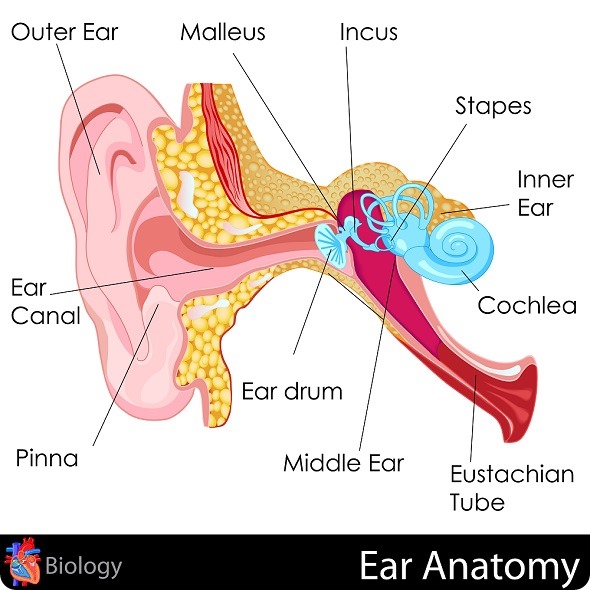

Otosclerosis affects the small bones in the middle ear. More specifically, it affects the stapes, which is actually the smallest bone in the body.

© snapgalleria / Shutterstock.com

Normally, these middle ear bones play a really important role in conducting sound vibrations from the eardrum to the inner ear. In otosclerosis, a bony growth develops on the stapes that causes it to become fixed. It then can't vibrate, so the sound vibrations can no longer pass into the inner ear.

We know that otosclerosis can be inherited and in about a quarter of cases, there's a strong family history.

Researchers have known for a long time that there is a genetic component. Until the publication of the research that we funded, we had no idea of the identity of the actual genes involved, so our research is important because it identifies the first gene that can cause this conductive form of hearing loss.

What did scientists at the Ear Institute at University College London recently show with regards to the SERPINF1 gene?

They're really interested in trying to identify which genes cause this condition. They studied ten people from four different families that had inherited otosclerosis.

They used whole exome sequencing, which is where you sequence all the coding parts of the genome, so the parts of the genome that encode proteins. They sequenced the entire exome of these ten people.

They then looked for changes in the DNA sequence that correlated with otosclerosis, which narrowed them down to nine possible genes. Then, they looked at another 53 people with a history of inherited otosclerosis, which narrowed it down even further, to SERPINF1. Through this filtering process, that’s the gene that they found.

They've gone on to identify six different changes to the gene that can cause otosclerosis. In the study, they were actually also able to collect the stapes from the patients because, often, that's removed as part of the treatment. By analyzing these bones they were also able to show that SERPINF1 was switched on and expressed in the stapes. They also showed that the mutations reduced the level of expression of the gene. This is all consistent with SERPINF1 causing otosclerosis.

What does this gene reveal about the biological processes involved in the development of otosclerosis?

SERPINF1 encodes a protein called pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF), which is a serpin peptidase inhibitor. It is known to bind to collagen. We also know that it's involved in bone growth and bone repair.

Interestingly, the same gene can cause brittle bone disease. The mutations are different, but they occur in the same gene. There's a good link to bone growth processes and I think the gene definitely gives us a clue and a way in to developing new treatments for otosclerosis.

The research has also found that, even in people that don't have mutations in this gene, its expression is still down regulated when they have otosclerosis.

The gene seems to be part of a pathway that could be common to a large proportion of otosclerosis cases, which makes it a very attractive target. A therapy that targets this gene could not only help people who actually have otosclerosis because of mutations in SERPINF1, but it might also help those who don't, because it seems to be part of a common mechanism.

How many different changes in SERPINF1 did you identify that can cause the condition?

They’ve identified six different mutations. All of these mutations ultimately reduce the amount of this protein in the stapes. Interestingly, there are two versions of SERPINF1; a long form with eight exons and a shorter form, which has just four exons. That shorter form is more commonly found in the stapes. It is perhaps a more ear-specific version of the gene.

Interestingly, three of the mutations found that cause otosclerosis were found to affect the shorter version of SERPINF1, which might explain why not everyone who has otosclerosis has the brittle bone disease which is also associated with this gene. It might just be that the shorter form of the gene is more relevant to hearing.

Are there likely to be more genes that cause this common form of deafness?

Definitely. It's hard to know how many more there are. Within the study that we funded, they looked at 57 individuals and mutations in SERPINF1 accounted for 10% of inherited otosclerosis in that small population. Clearly, there are other genes involved.

We're actually funding another study at the Ear Institute to look at a further 57 cases of otosclerosis, to try to identify more genes. It will be really interesting to find out whether they're in completely different biological pathways or in the same pathway.

If they're in the same pathway, then it perhaps gives us more hope that a single treatment can be developed to help a wide range of people. If the study starts to suggest there are lots of different biological pathways, then we'll probably need more than one treatment.

How is otosclerosis currently treated and do you think this research could lead to the development of drug treatments to prevent abnormal bone growth on the stapes?

Our ultimate goal in funding this research is, obviously, to develop much needed treatments for people who've got hearing loss.

At the moment, the only way the condition can be treated is either by giving people hearing aids, which can help improve hearing or, if it gets really bad, by performing surgery to remove the damaged stapes. Often, that's replaced with a prosthetic device, but the success rate varies.

Typically, you might get a 20 dB improvement in about 80% of patients. Therefore, although there are some treatments, they're not ideal and we definitely need better ones.

Understanding the biological processes involved throws the door wide open to being able to develop drug treatments to intervene and block these processes that are going wrong. Identifying this first otosclerosis causing gene is the first step.

The middle ear is also an attractive part of the body to deliver drugs to because it's quite accessible; it's easy to inject drugs through the eardrum. It's also a relatively self-contained organ, so we could deliver drugs locally and not have to worry too much about side effects in other parts of the body.

What further research is needed to understand the genetics of otosclerosis?

We urgently need to find the other genes that are playing a role. We definitely know there are more out there. We're funding more research using exactly the same techniques to identify these.

We also now need to develop and study animal models of otosclerosis to really understand how changes in SERPINF1 cause otosclerosis. We need to find out what's actually going on and what we need future drug treatments to do.

In what ways do Action on Hearing Loss hope to improve hearing loss research moving forwards?

Research into hearing loss is incredibly important, but it's neglected. There are 11 million people in the UK that have hearing loss, most is age-related. We know that by 2035, there will be 15.6 million people with hearing loss.

Hearing loss can really affect people's lives, causing them to feel cut off and isolated. It's a really neglected and invisible condition. The treatments for it are also really limited.

At the moment we have hearing aids and cochlear implants. We definitely recommend people make use of this technology, but they are really just a sticky plaster over the problem. What we really want to do is drive forward research so that in the future there are treatments to actually prevent the progression of hearing loss, as well as treatments to repair the root causes of hearing loss, so people get back natural hearing.

We're also really interested in tinnitus – the ringing people get in the ears or head when there's no obvious sound to cause it. Again, it's really common, but there's no cure and no treatment to make it go away.

We're funding the training of scientists so that in the future, we have more scientists working on treatments for hearing loss and tinnitus. We're funding break-through research like the otosclerosis research we've just been talking about, to make discoveries that will lead to treatments in the future.

We're funding research into stem cells, which we think hold great promise. Our research has already shown that stem cells can repair damage to the ear and restore hearing in animals and we are now funding research to develop safe and efficient ways of delivering stem cells into the ear. We're also working to make sure that when discoveries are made, that they are taken forward by the pharmaceutical industry and actually turned into treatments.

We work closely with pharmaceutical companies, to encourage and support their involvement in developing hearing treatments. We also fund research into the later stages of development, where evidence is needed to demonstrate that a particular treatment is likely to work in humans.

These kind of translational research projects aim to progress promising new treatments to a point where they attract private investment from pharmaceutical companies. For example, we've just started funding a new project with a biotech company called PRAGMA in France, to develop a drug that we hope will lessen hearing loss following exposure to a loud noise, which is clearly a problem in the military.

Finally we're a charity. Everything that we fund, we raise from donations and we rely 100% on the generosity of our supporters. We urge everyone to help us raise awareness of how important research into hearing loss is and to help us support more research.

Where can readers find more information?

About Dr Ralph Holme

Dr Ralph Holme is Head of Biomedical Research at Action on Hearing Loss. He is responsible for the charity’s biomedical research program which aims to accelerate the discovery and development of new medical treatments to prevent, and ultimately cure, deafness and tinnitus. This involves funding world-class research and training, working closely with the pharmaceutical industry and campaigning for increased investment in hearing research.

Before joining the charity, Ralph was a Postdoctoral Scientist at the MRC’s Institute of Hearing Research in Nottingham investigating the genetic basis of deafness. Ralph completed his PhD on vertebrate eye development in 1998 at the MRC’s Human Genetics Unit in Edinburgh.