Mar 16 2017

Scientists from the Florida campus of The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) have developed a new drug delivery method that produces strong results in treating cancers in animal models, including some hard-to-treat solid and liquid tumors.

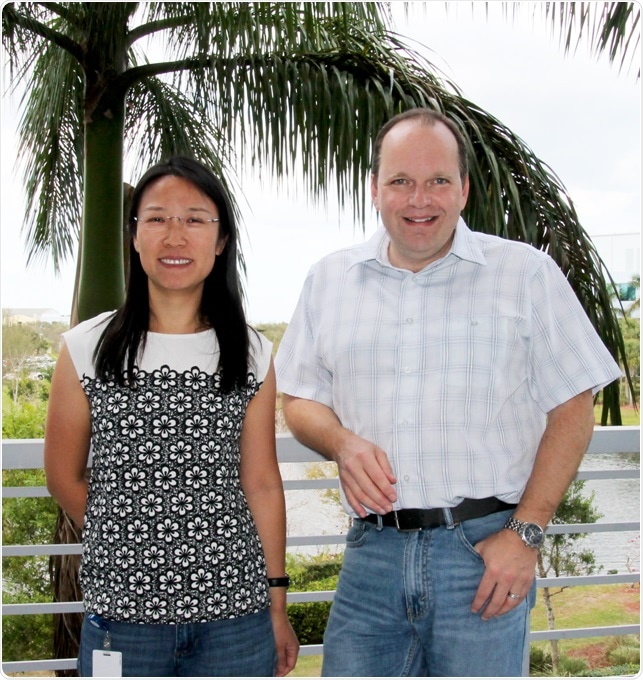

Research Associate Xiuling Li (left) and Associate Professor Christoph Rader led the study on the Florida campus of The Scripps Research Institute. (Photo by Junpeng Qi.)

The study, led by TSRI Associate Professor Christoph Rader, was published March 16, 2017, online ahead of print in the journal Cell Chemical Biology.

The new method involves a class of pharmaceuticals known as antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), which include some of the most promising next-generation antibody therapeutics for cancer. ADCs can deliver a cytotoxic payload in a way that is remarkably tumor-selective. So far, three ADCs have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), but neither attaches the drug to a defined site on the antibody.

"We've been working on this technology for some time," Rader said. "It's based on the rarely used natural amino acid selenocysteine, which we insert into our antibodies. We refer to these engineered antibodies as selenomabs."

Antibodies are large immune system proteins that recognize unique molecular markers on tumor cells called antigens. On their own, Rader noted, antibodies are usually not potent enough to eradicate cancer. However, their high specificity for antigens makes them ideal vehicles for drug delivery straight to tumor cells.

"We now show for the first time that selenomab-drug conjugates, which are ADCs that utilize the unique reactivity of selenocysteine for drug attachment, are highly precise, stable and potent compositions and promise broad utility for cancer therapy."

Along with its potency, Rader noted, the ADC's stability is critical to its effectiveness. The researchers found that their new ADCs showed excellent stability in human blood in vitro and in circulating blood in animal models. Moreover, the new ADCs were highly effective against HER2 breast cancer, a particularly difficult cancer to treat, and against CD138 multiple myeloma. Importantly, the ADCs did not harm healthy cells and tissues.

"The selenomab-drug conjugate significantly inhibited the growth of an aggressive breast cancer," said TSRI Research Associate Xiuling Li, first author of the study. "Four of the five mice tested were tumor-free at the end of the experiment, a full six weeks after their last treatment."

The researchers plan to investigate similar ADCs going forward. Rader, along with TSRI Professor Ben Shen, was recently awarded $3.3 million from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health to test highly cytotoxic natural products discovered in the Shen lab using selenomabs as drug delivery vehicles.