Hyperglycemia occurs when a patient has higher than normal blood sugar levels. If the levels are very high, consistently 13-14 or above, the patient will start to feel tired, thirsty and feel the urge to go to the toilet frequently to pass urine (micturition).

If there is a high amount of sugar circulating in the blood you feel like you have no energy. Because your brain doesn't get enough energy you also feel sleepy, especially following a meal. Patients also experience poor ability to concentrate, and so experience a reduction in their productivity.

Why is good mealtime control so important and what complications can regular hyperglycemia after meals increase the risk of?

Post-prandial hyperglycemia is linked to a higher risk of macrovascular disease (which will lead to cardiovascular disease such as heart attacks). Like most complications in diabetes, if intervened in the early stages these harmful effects are reversible. In later stages, however, they become irreversible and result in long term damage to the patient.

When we eat, different types of foods release their sugar at different rates. This means that the maximum glucose level in the blood will be reached at different times following a meal, depending on the food type itself. For example, if you're eating a very rich carbohydrate meal, your blood sugar levels can shoot up very quickly, within an hour you can almost reach double the amount that you may have before you had the meal. Because of this sudden rise in blood sugar level, it results in a series of reactions within the body, and if this is repeated for a long period of time complications can arise, which include a higher risk of heart attack.

High sugar levels can also have an effect on the back of your eyes, damaging them, and on the kidneys as well. Those are all the long-term damages of consistently high sugar levels. Once you start to have those kinds of problems then it becomes difficult to reverse them.

What did a recent survey find with regards to the number of people with diabetes that discuss hyperglycemia with their healthcare professional?

The survey showed that two-thirds do not discuss high blood sugar levels with their healthcare professional. It's only the patients who have really high blood sugar levels during the night, when they wake up to go and pass urine during their sleep, discussed this with their doctors.

It is not until they are waking up several times in the middle of the night to pass a lot of urine do patients often feel the need to express concern with their doctor and associate it with diabetes. Whereas when it happens in the daytime, patients don't often make this association with uncontrolled blood sugar levels.

In the UK traditionally, and across the world as well, we look at controlling the blood sugar levels, what they are before you eat. For example, we encourage patients to check their levels first thing in the morning, because if you start the day well, then the day is likely to be better in terms of sugar control.

Because of this emphasis of monitoring blood sugar levels at baseline (before meals), we somewhere along the line stopped emphasizing the importance of what patients’ levels are after they have food. This causes patients to often overlook symptoms of tiredness, poor concentration or frequent passing of urine in the daytime and so they don't inform their doctor of these symptoms.

When are the best times to test blood sugar levels?

In addition to fasting levels, usually we say a blood sugar level test should be taken about two hours after you've eaten the meal, but there is a debate whether it is one hour, one and a half hours, or two hours.

There's one situation where that debate has been settled and that is when a woman has diabetes becomes pregnant. In this case, we actively make the woman get test exactly an hour after they've eaten each meal. That's because we know there is a strong link to the risk of having overweight babies and the mother with diabetes; whereas when it comes to non-pregnant women and men, there is a debate as to when a blood test should be taken.

This is because, as I mentioned earlier, blood glucose levels following a meal depends on what type of food you eat and not just the time frame following a meal. For example, breakfast which is rich in carbohydrates, as most of us eat cereals or a couple of pieces of toast, which is made up of nearly 80%-90% carbohydrate or starchy food. Such breakfast will result in maximum glucose rise one hour following consumption. Whereas a proper mixed lunch meal may take a longer time, for example one and a half to two hours before reaching the maximum rise in glucose level.

The HbA1c test is an average estimate of the overall previous two to three months of glucose control. So when we see patients with good control when fasting, their HbA1c can be higher if their postprandial glucose levels are not controlled. That is cause for concern and we should focus on the postprandial glucose levels. For non-pregnant adults we can typically test two hours following a meal, in order to try and standardize the test. That’s why if you're a patient and you're worried about how high your blood sugar levels go, I always use two hours and would recommend trying to maintain consistency.

Patients can also carry out the test for themselves and compare the different types of meals and the effect on their glucose levels, so they know how much sugar is released from particular meals. It’s also important to know that we all react differently to the same food, therefore if two people have the same size slice of pizza, one may release the sugar in a slightly different rate to how the other would release.

Why did patients choose not to discuss their symptoms? What were the main reasons given?

Some accept that this is part and parcel of having diabetes, especially if the patient has been suffering from diabetes for a long time. Significant others do not link the symptoms to high glucose levels (as they are not usually expected to test their blood glucose levels after meals) and some are worried that they will get ‘told-off’ by not taking/managing their insulin regularly.

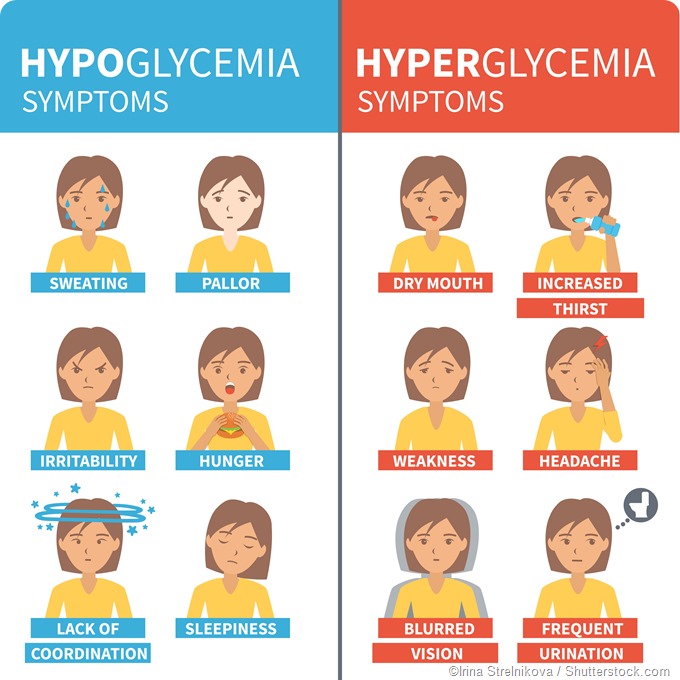

As a healthcare professional what I worry about in diabetes patients is hypoglycemia, especially when they are on certain treatment which can reduce their glucose levels too low. Hence there is a big emphasis on talking about hypoglycemia. But hyperglycemia is not emphasized enough.

Some patients actually felt that they might get told off by their doctor if they had come up with the symptoms and they might say, well, you're eating the wrong type of food etc., however quite a lot of it is down to not being aware of it and not linking those symptoms to high glucose levels are the two main categories.

What can healthcare professionals do to aid discussion of hyperglycemia?

Healthcare professionals should always enquire proactively about hyperglycemia, encourage them to bring up these symptoms and look out for them ourselves at the same time as a routine check, as well as educate the patients to look out for these symptoms themselves.

It is important because the patients are not necessarily aware of hyperglycemia and it will cause slow damage over a long period of time. Predominant symptoms like tiredness, thirstiness and passing a lot of water could be outlined in a simple leaflet for patients and help give them more information about hyperglycemia.

A leaflet is a good method of educating patients because it does not take much of the professional’s time and can be given by a number of health professions such as a GP, nurse or a hospital healthcare professional.

What more needs to be done to educate people with diabetes about hyperglycemia? What current resources are available?

I don't think we have enough information specific to this condition, information is always wrapped up the symptoms and problems of diabetes. As I mentioned previously, there needs to be the introduction of specific ‘hyperglycemia’ leaflets, which will aid in focusing our consultations and education of our patients.

There are lots of specific information leaflets about hypoglycemia, because if patients are on certain medication that can cause hypoglycaemia must inform the DVLA as this is a legal requirement for the patients about hypoglycemia. Hence there are leaflets specifically designed for hypoglycemia. No such requirement is necessary for ‘hyperglycaemia’ and hence doesn’t get the same attention.

This survey highlights the patients don’t know enough. Yes, this information is probably provided to them, but may not be in a focused way. If you have a specific brief information leaflet to draw the attention of a patient a bit more carefully, and if they then experience these things they'll be more likely to bring it up with their healthcare professionals.

What do you think the future holds for managing diabetes and minimizing hyperglycemia?

The future is exciting, as an academic I do research in to find new ways of understanding the disease and ways of prevention. There are a lot more options nowadays available for managing the condition, helping patients diagnosed to control it and limit long-term damage. We know if we provide a comprehensive approach we can reduce the complications by up to 60%-70%, if not more.

In the past there used to be just a couple of tablet groups and insulin, in terms of therapy options, whereas now we have six, seven different groups of therapy that are available for treating diabetes with slightly different mechanisms of action.

A larger variety of therapy options gives greater flexibility for healthcare professionals to individualize and choose the right drug, the right insulin, for that particular patient based on their specific needs. In that sense, I think the future is exciting, and this field is growing rapidly, so we have a lot more therapy options in the future.

The way I would see it is if the patients take charge then they can control diabetes much better than letting the diabetes rule or control their life.

Where can readers find more information?

Diabetes UK has lot of information available for the patients in their website. In addition, Diabetes team, Warwick Medical School and George Eliot Hospital, United Kingdom.

About Dr Saravanan

Dr Saravanan is an Associate Clinical Professor and Honorary Consultant Physician in Diabetes, Endocrinology & Metabolism at Warwick Medical School, University of Warwick & George Eliot Hospital, United Kingdom.

Dr Saravanan is an Associate Clinical Professor and Honorary Consultant Physician in Diabetes, Endocrinology & Metabolism at Warwick Medical School, University of Warwick & George Eliot Hospital, United Kingdom.

He did his research in Bristol and his specialist training in Bristol & Exeter. For his PhD, he conducted the world's largest clinical trial on the effects of combined T4/T3 (thyroid hormone replacement). His thyroid work was instrumental in changing the combined guidelines issued by American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists & American Thyroid Association.

Currently, Dr Saravanan pursues his long term interest in to the mechanisms of ethnic variations in Diabetes. He passionately believes in 'primordial prevention' of metabolic disorders and hence focuses on health of young women and Gestational Diabetes.

He currently leads 3 multinational studies; all received prestigious funding from Medical Research Council, UK (MRC). These projects involve collaboration with world-renowned institutions in the UK, India, Kenya and Malaysia. These projects are recruiting 4500, 3500, 4000 and 5000 women in UK, India, Kenya and Malaysia respectively.

He strongly believes in reducing the variations in the management of Diabetes in the UK. He is the academic lead of the team that won several awards including the prestigious NHS Innovation award worth £100,000 for integrated care in BME population with Diabetes.