Apr 21 2017

Researchers at Okayama University report in the Journal of Artificial Organs the promising performance of a retinal prosthesis material when implanted in rats. The material is capable of converting external light stimuli into electric potentials that are picked up by neurons. The results signify an important step towards curing certain hereditary eye diseases.

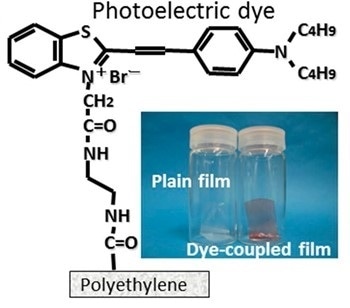

The main component of Okayama University-type retinal prosthesis (OURePTM) is a photoelectric dye molecule, the structure of which is shown. The dye molecules are attached to a polyethylene film, resulting in a promising retinal implant. Quantitative testing experiments were done on the response of dye-coupled (OURePTM) films and plain films, implanted in rats, to flashing LED light.

Retinitis pigmentosa is a hereditary retinal disease, causing blindness due to dead photoreceptor cells but with other retinal neurons being alive. A potential remedy for patients diagnosed with this disease are prostheses replacing the non-functioning photoreceptor cells with artificial sensors, and making use of the functioning of the remaining, living neurons. Now, a team of researchers from Okayama University led by Toshihiko Matsuo & Tetsuya Uchida has quantitatively tested the response of a promising type of prosthesis, when implanted in rats, to external light flashes — a crucial step in the further development of retinal prostheses.

The prosthesis tested by the researchers was developed earlier at Okayama University, and is known as Okayama University-type retinal prosthesis (OURePTM). The main component of OURePTM is a photoelectric dye: an organic molecule capable of converting light into electric potentials. Uchida and colleagues attached the dye molecules to a thin film of polyethylene — a safe and stable biocompatible material — and implanted the dye-coupled film (of size 1 mm x 5 mm) subretinally in the eyes of 10 male rats 6 weeks old. Cranial electrodes for registering potentials were attached 2–3 weeks later. The researchers also implanted plain, polyethylene films in 10 other rats for comparison purposes.

The scientists tested the response of the implanted OURePTM sensors to flashing white light-emitting diodes (LEDs) placed on the surface of the rats’ corneas (the transparent front parts of the eyes) for different background-light conditions. The experiments were done with the rats anesthetized, and after appropriate periods of adaptation to dark or light conditions. Comparisons between results obtained with dye-coupled films and plain polyethylene films showed that the former led to visually evoked potentials — confirming the potential of OURePTM as a retinal prosthesis for treating diseases like retinitis pigmentosa.

The use of OURePTM poses no toxicity issues and, because of the high density of the dye molecules on the polyethylene film, offers a high spatial resolution. Regarding tests on human eyes, Matsuo and colleagues point out that “a first-in-human clinical trial for OURePTM at Okayama University Hospital ... will be planned in consultation with [Japan’s] Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency”.