Researchers have used a genome-editing technique to elucidate the role of a gene that is key to human embryonic development.

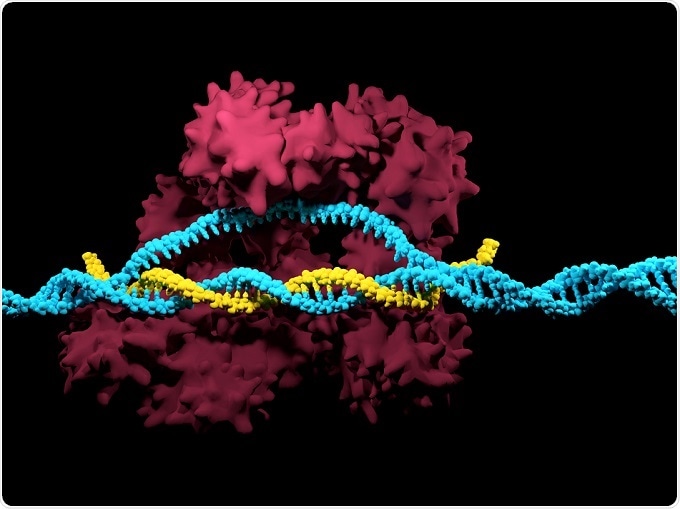

CRISPR-Cas9. Credit: Meletios Verras/Shutterstock.com

CRISPR-Cas9. Credit: Meletios Verras/Shutterstock.com

This is the first time that genome editing has been used to study the function of genes in human embryos, which could help scientists improve their understanding of early human development, transform IVF techniques and explain pregnancy failures.

The technique, called CRISPR/Cas9, was used to remove a gene (in 41 embryos) that codes for a protein called OCT4, which is usually activated during the first few days of embryonic development.

Following fertilization, an egg starts to divide and after about seven days, it becomes a ball-shaped structure called a blastocyst, which later forms the placenta.

The study showed that removing the OCT4-producing gene prevented the embryos form correctly forming the blastocyst, suggesting the gene is key to this process.

Lead author Kathy Niakan (Francis Crick Institute, London) says she hopes the technique can be used by others to identify a whole host of genetic factors that affect pregnancy, but are currently poorly understood: “One way to find out what a gene does in the developing embryo is to see what happens when it isn’t working. Now we have demonstrated an efficient way of doing this, we hope that other scientists will use it to find out the roles of other genes.” Niakan thinks that if scientists could establish the main genes needed for embryos to grow properly, pregnancy failure could be better understood and IVF treatments improved.

As well as potentially revolutionizing IVF and helping couples to become pregnant, researchers say the technique could also lead to advances in regenerative medicine, as OCT4 is also thought to be important in stem cell biology. “Pluripotent” stem cells, which can be derived from human embryos, can form any type of tissue in the body and scientists use stem cell technology to create tissue that can repair damage or replace missing structures in the body.

Co-author of the study, James Turner, says that although the technology is currently available to create and use pluripotent stem cells, experts still don't understand exactly how these cells work:

Learning more about how different genes cause cells to become and remain pluripotent will help us to produce and use stem cells more reliably."

The research, which was published in Nature was a collaborative effort by scientists from the Francis Crick Institute, Oxford University, Cambridge University, the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Seoul National University and Bourn Hall Clinic. Funding was mainly provided by the UK Medical Research Council, Wellcome and Cancer Research UK.