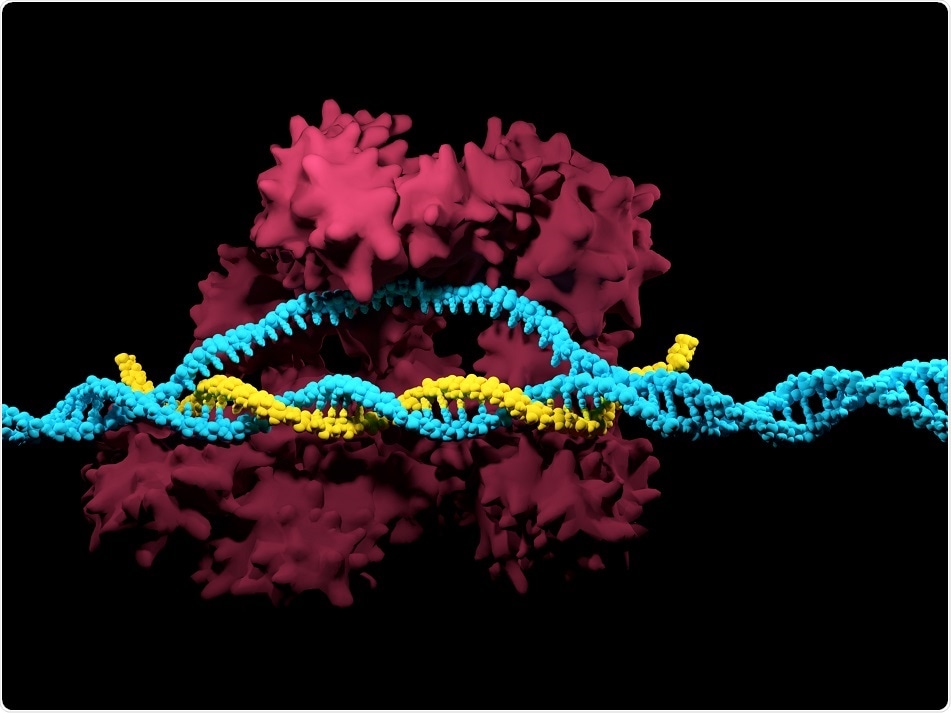

Researchers have developed a CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing complex that can be delivered directly into hair cells of the inner ear to prevent hearing loss.

Credit: Meletios Verras/ Shutterstock.com

In a mouse model of human progressive genetic progressive deafness, researchers from the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard delivered the complex directly into the hair cells of the inner ear, where it disrupted the gene known to cause hearing loss.

Hearing loss is the most common type of sensory loss in humans and almost half of cases involve an underlying genetic element. Inner ear hair cells are specialized cells that convert sound wave vibrations into electrical signals that the brain interprets.

One underlying cause of genetic hearing loss is a mutation in the TMC1 gene that causes these hair cells to produce an abnormal, toxic protein that accumulates in the cells and eventually kills them. The mutation causes progressive hearing loss in young individuals, who eventually become deaf.

As reported in Nature, by using the CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing complex to disable the mutated gene, the researchers were able to preserve the inner ear hair cells in mice that were otherwise genetically destined to become deaf.

The gene-editing mix was injected into the cochlea of new-born mice with the TMC1 gene mutation. Left untreated, the mice would have experienced hearing loss at four weeks of age and profound deafness at eight.

At four weeks, mice that were not given the treatment had a detectable brainstem response to sounds of around 80 decibels, about the volume of a loud radio, whereas mice that were given the treatment had responses to sound starting at around 65 decibels, about the volume people generally speak at.

Physiological measurements showed that the treated mice had a higher rate of inner ear hair cell survival than untreated mice and genetic sequencing of the edited cells showed that the TMC1 gene had successfully been disabled in 94% of cases.

The team now intends to develop the treatment in larger animal models of genetic progressive hearing loss.

"These results inform the potential development of a treatment for a subtype of genetic hearing loss, but making sure the method is safe and effective is critically important before we propose moving closer to human trials," says co-senior author Liu.