Currently, the way that breast cancer risk is assessed is through a combination of standard risk factors. One of the easiest methods of identifying people at high-risk is through family history, where individuals with first degree relatives who were diagnosed with breast cancer at a young age show the highest risk.

Other risk factors include hormonal and reproductive factors. For example, we know that the earlier you have your first pregnancy, the more protective it is. In turn, if you delay your first pregnancy beyond 30, you lose that protection and potentially increase your risk.

The age at which a woman starts and ends her periods is also important. Women who start periods young and finish later are at an increased risk of breast cancer because the breasts are exposed to estrogen for longer.

Then there are some lifestyle factors, in particular, weight gain or being overweight after menopause can significantly increase your risk.

How are these risk factors used to determine breast cancer screening and diagnostic practices?

Essentially, we have standard algorithms that put together all of these risk factors and calculate a risk over usually a five or ten-year period, and then the entire person's lifetime; up to around 80 or 85 years of age.

The standard risk factor algorithm that we use is called the Tyrer-Cuzick model, named after the two people that developed it, which appears to be the most accurate. The algorithm uses all of those standard risk factors to calculate a woman’s risk over the next ten years and the rest of her life, and compares this to the breast cancer risk of the average woman at that particular age.

Now, the two additional methods that we have for assessing risk are mammographic density (the density of the breast tissue on the mammogram) and genetics.

Mammographic density is proving to be a very important assessment for risk. The denser the breast tissue is on the mammogram, the greater the risk. Another way of putting it is, the less dense (or more fatty) the breast appears on the mammogram, the less risk there is.

From the fattiest breast, up to the most dense breast, there's about a fivefold difference in risk. So, from looking at density alone, your lifetime risk could go from 1 in 20 for the least dense breast to around 1 in 4 for the most dense.

Finally, we have the genetics, for which there are very few elements. We currently test for high risk genes, including BRCA1, BRCA2 and TP53 genes, amongst others and moderate risk genes including CHEK2 and STM. However, only about 2% of the population carry faults in these genes, or causative genetic faults in these genes.

For the general population; particularly those without a family history of breast cancer, testing for high and moderate risk genes actually has little impact on risk, as they are unlikely to carry faults in these genes. But, if you have a very strong family history of breast cancer, carrying out these sorts of genetic tests can be very important in assessing your risk.

What are single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and how many are associated with breast cancer?

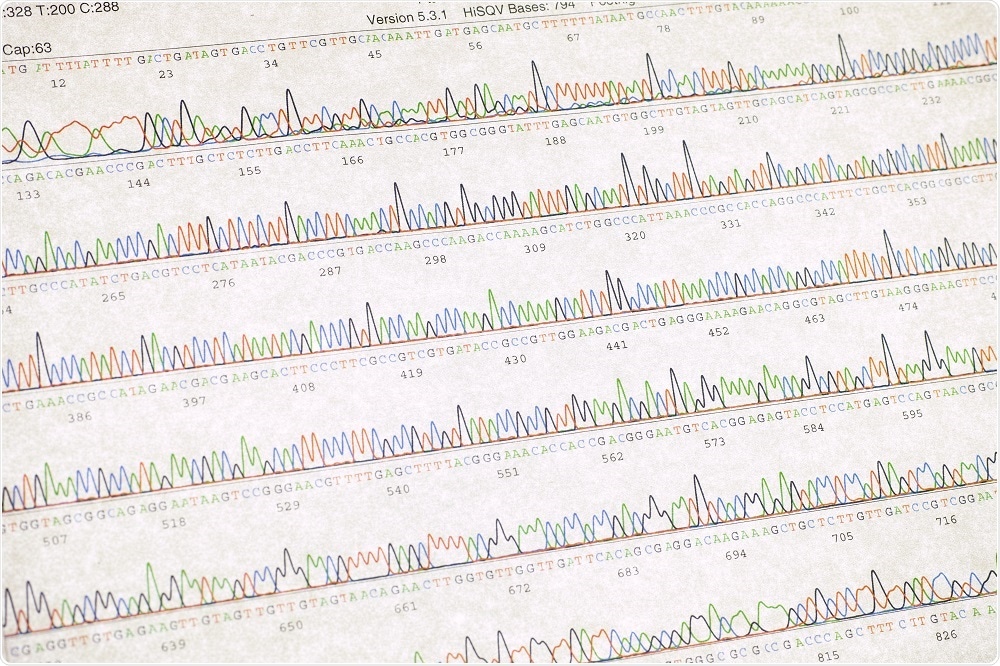

The second element to genetic testing is testing for common genetic factors (or variants) called SNPs, or single nucleotide polymorphisms. These are changes of just one letter in the genetic code.

There are currently more than 200 SNPs that have been implicated in breast cancer risk. SNPs are very common; many of them can be found in 40%, 50%, 60% of the population. To be considered as a risk factor, they have to at least occur in 5% in the population.

Individually they only slightly alter your risk by a factor by 5% or 10%, up to about 20%, but if you multiply them all together you get a polygenic risk score. That gives a calculation of your overall risk; a genetic risk for every person in the general population. This means that every single person can have their risk assessed using a polygenic SNP score.

If you compare this to testing for BRCA1 and BRCA2, if you test negative and you don't have a family history, it makes zero difference to your risk. You might be reassured that you don't carry faults in a high-risk gene, but the likelihood that you had one in the first place was so small that excluding high-risk genes makes no real difference to your overall chances of developing breast cancer.

The way that we calculate risk now is by putting the standard risk factors into the Tyrer-Cuzick model, adding in information from the mammogram, and then finally carrying out a SNP test. The algorithm can now put all three together and come up with an overall risk factor for each woman.

Why is it important that we implement SNP profiling into breast cancer risk assessment?

I think that we should be doing population screening and prevention better than we are currently doing. The one size fits all is, "Let's invite every woman, when they reach 50 years of age, for three yearly screening." But the general population isn’t one size; it’s many different sizes, and there’s a proportion of people at age 50 who have an extremely low chance of developing breast cancer.

For these people, screening risks may outweigh the benefits. In other words, they have a higher proportional chance of being mistakenly diagnosed with breast cancer and being treated for something that would never cause them any problems.

It also allows us to identify about one in six of the population who fit into what NICE define as having a moderate or high risk of breast cancer. This is important because of those one in six, ~18% develop nearly half of all stage two cancers.

This is a group that we should be doing screening more frequently in, that's a group that we should be offering, or considering, preventative drugs which can reduce the risk of breast cancer after menopause.

Credit: SINTAR/Shutterstock.com

Please outline your research and current projects in the field of breast cancer risks and SNPs.

We recently published a study in the JAMA Oncology, which involved SNP testing 10,000 women who volunteered as part of the Greater Manchester screening population. We measured their standard risk factors with the Tyrer-Cuzick model, their mammographic density, and then we carried out a SNP test which included 18 SNPs.

We used to data to segregate women into risk categories (high, low or average). Women in the high risk categories qualified for extra screening or chemoprevention drugs. We found that the test was highly accurate and saw that the rates of cancer that were expected were the rates of cancer we actually saw.

What options will this provide to women who find out they are at risk of developing breast cancer?

As a result of the study we are going to start telling women what their risks are at their first screen. If they are in the high or moderate risk category, we will offer them more frequent mammograms and they are at low risk, talk to them about delaying screening for another 10 years.

Some women will even have sufficient risk to consider surgery as a preventative option, but that would be an unusual situation for someone without a genetic mutation such as BRCA1/2.

An insight into the future of Cancer Prevention and Early Detection – NIHR Manchester BRC

Credit: NIHR Manchester Biomedical Research Centre/Youtube.com

Do you think SNP profiling will become common practice in healthcare? Could it be applied to any other cancers?

Yes, I think SNP profiling is really should come in. It is a vital part of risk management and is cheaper than traditional genetic tests. At the moment, its accuracy is only been proven for breast cancer, but I think SNP testing will soon be introduced for prostate and lung cancer screening, amongst many others.

What do you think the future holds for breast cancer risk assessment?

I think there is still room for improvement. Increasing the number of SNPs involved in the SNP test will be one factor. Another factor will be making sure that any new SNPs are accurate. The current paper shows the fantastic accuracy of SNP 18, and we know that adding more SNPs will improve accuracy, however we need to ensure we are not giving women exaggerated risks.

Where can readers find more information?

About Dr Gareth Evans

Dr Gareth Evans is a Consultant in Medical Genetics and Cancer Epidemiology at The Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust and The Christie NHS Foundation Trust.

Dr Gareth Evans is a Consultant in Medical Genetics and Cancer Epidemiology at The Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust and The Christie NHS Foundation Trust.

He has established a national and international reputation in clinical and research aspects of cancer genetics, particularly in neurofibromatosis and breast cancer.

Dr Evans is lead clinician on the NICE familial breast cancer guideline group and until recently, a trustee of Breast Cancer Now and the Neuro Foundation. He has published 706 peer reviewed research publications; 261 as first or senior author. He has published over 100 reviews and chapters and has had a book published by Oxford University Press on familial cancer.