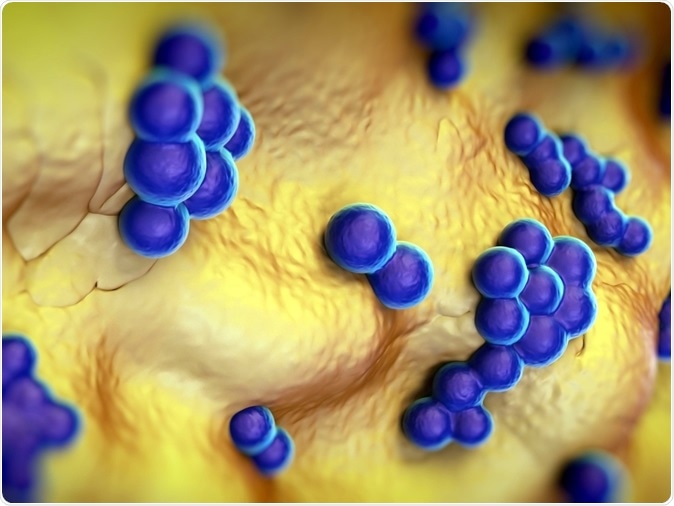

With the advent of multi-drug resistant bacteria and lack of new antibiotics, researchers have been on the lookout for new molecules that can fight these pathogens. A team of researchers have now identified a slimy mucous coating of young fish as a potential source for antibiotics that could fight resistant infections such as MRSA (Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus).

Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteria 3d illustration: Credit: Shutterstock

The results of the study were presented at the American Chemical Society (ACS) Spring 2019 National Meeting & Exposition.

Lead researcher Sandra Loesgen from the Oregon State University, in a statement said, “We believe the microbes in the mucus add chemistry to the antiseptic power of the mucus and that new bioactive compounds might be discovered from the fish microbiome...For us, any microbe in the marine environment that could provide a new compound is worth exploring.”

She added that there are several chemical reagents in the human microbiota (present in the gut and mucosal surfaces of humans) as well as on marine life. These have not yet been explored she said. She said that there us a mucus coating on the surface of fish. It is rich in microbes that protect the fish. This is a thick viscous slimy substance that can protect the fish from bacteria, fungi and viral attacks from its environment. The slime is capable of trapping these pathogens before they can penetrate the skin. This slime is also found to be rich in complex sugars called polysaccharides and complex proteins called peptides. These compounds have shown antibacterial activity say the researchers.

Molly Austin, an undergraduate chemistry student, who was part of some of the experiments said, “Fish mucus is really interesting because the environment the fish live in is complex. They are in contact with their environment all the time with many pathogenic viruses.”

A co-author on the study, Erin (Misty) Paig-Tran, from California State University, Fullerton, provided this team with the mucus that was obtained from the young ones of deep-sea and surface-dwelling fish from the Southern California coast. They noticed that the mucus was more abundant among young fish as they needed to fight off infections more because of their immature immune systems. Loesgen, along with Austin and another graduate student Paige Mandelare, looked at the mucus and its capacity to fight off 47 different strains of bacteria.

The team was surprised to see that five extracts of the slime could fight off MRSA while three of the extracts were capable of fighting off fungus Candida albicans. One particular strain of bacteria from the surface of Pacific pink perch was found to fight both MRSA as well as a cell line from colon cancer. The team is also on the lookout for extracts that could fight Gram-negative bacteria - Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which is difficult to treat.

The researchers add that their experiments might help reduce antibiotic use in fish farming as well. The reduced use of antibiotics on fish would enhance the production of this slime with antibacterial properties they explain.

Loesgen said that as of now they are not clear on the natural antimicrobial picture on fish. They add that they do not know if the extracts they studied from the fish were normally found. Their next step in the research would be to understand that normal microbiome over fish surface, explains Loesgen.