Isabelle Carnell-Holdaway is a British teenager with cystic fibrosis. When she was 15, Isabelle underwent a lung transplant at Great Ormond Street Hospital, and whilst recovering, developed a life-threatening, multi-drug resistant infection.

Realizing that antibiotics were not going to work, doctors decided to try an experimental treatment in the form of genetically engineered viruses (known as bacteriophages) that infect and kill bacteria. The treatment was highly successful, and the details of the case study were published in the latest issue of the journal Nature Medicine.

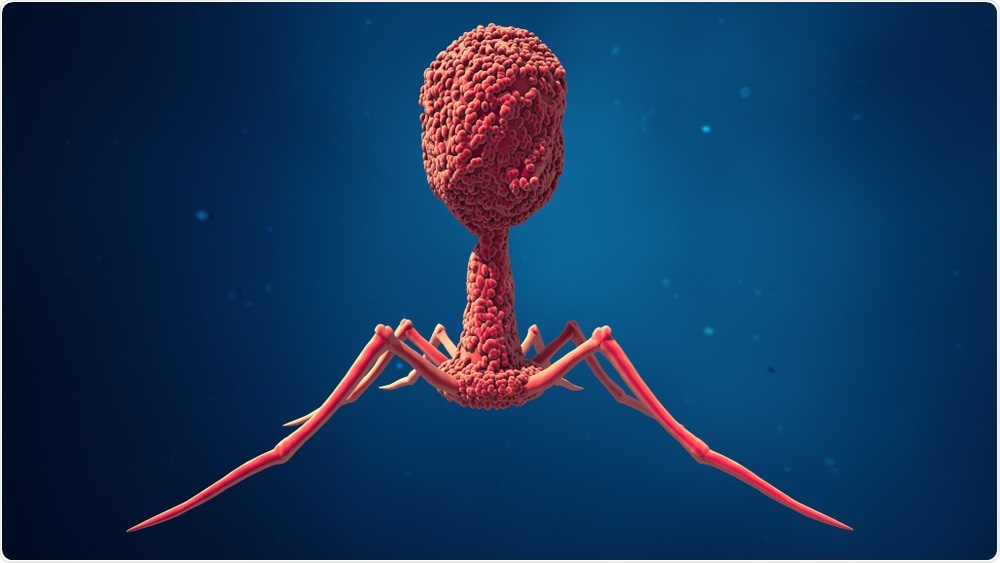

Design_Cells | Shutterstock

Design_Cells | Shutterstock

Isabelle's mother Jo Holdaway described the treatment process, saying:

We were at the point where there was no other hope, they said she wasn't going to leave the hospital and had less than 1 percent chance of survival.”

Isabelle was given a ‘cocktail’ of bacteriophages that targeted and killed the rogue bacteria. Thanks to the innovative treatment, she is back to taking her regular medication and is learning how to drive.

The treatment, known as phage therapy, has previously been investigated as a potential solution to antibiotic resistance. However, a large-scale roll out is unlikely to happen soon, as the treatment is still in the experimental stages and will need refinement, as well as large clinical trials, to prove that it is safe and effective.

The practice of using bacteria-engulfing viruses as treatment of severe bacterial infections has been around for nearly a century. It has not been used widely or tried in large clinical trials yet because bacteriophages are highly specific in the bacteria they target and need to be generated on a case-by-case basis. This means they cannot be used in emergencies where broad-spectrum antibiotics need to be administered immediately before the cause of the infection is known.

Unlike previous experiments, the researchers treating Isabelle used genetically modified phages which made them more effective than those occurring naturally.

This is the first person who has been treated for a mycobacterium infection with phage therapy that we’re aware of.”

Dr. Helen Fisher, Respiratory Paediatrician

‘Desperate for other options’

Following a lung transplant, Isabelle developed an infection within the healing wounds. This infection soon spread to her liver and the donated lung, causing her to spend the most part of the following year in the hospital.

She was incredibly sick. She had fulminant [acute] liver failure... She was pretty much bed bound, wasn’t eating at all, we were having to feed her intravenously... Isabelle’s parents knew we were trying to work on this phage therapy, so when the time came that we had no other conventional therapies to use and ongoing signs of infection – they were desperate for other options.”

Dr. Spencer, Senior Author

Professor Graham Hatfull, a microbiologist at the University of Pittsburgh was sent samples of Isabelle’s infection along with samples of another infected patient.

Professor Hatfull’s laboratory has a large collection of bacteriophages (over 15,000) that have never been used for therapeutic purposes. Professor Hatfull explained, “We were sent a few strains, from London, and set about testing whether the phages in our collection would be able to infect these particular bacterial strains.”

In January 2018, the researchers found a single bacteriophage strain (which they named ‘Muddy’) that was able to kill the bacterium causing Isabelle’s infection. They took this strain and two others and genetically modified them to increase their efficacy against the infection.

The experts believe that using more than one strain could help prevent the bacteria from mutating and becoming resistant to the bacteriophage, as they are being challenged by multiple phages at once.

‘A targeted strike’

The next step, which began in June 2018, involved the team giving Isabelle twice-daily infusions containing millions of genetically engineered bacteriophages. Within six weeks, the infection had disappeared from Isabelle’s liver completely. The team used a combination of the phages and antibiotics to treat the remaining infections in her skin.

Professor Hatfull called antibiotics “blunt instruments” and said, “With phages it’s the opposite end of the spectrum. They’re very specific, it’s a targeted strike, you’re not going to affect the rest of the microbiome and they’re low toxicity because they don’t infect human cells.”

However, “it’s a double-edged sword”, he said, “because they may target the strain infecting patient number one, but patient two or three, may have the same species of bacteria but the strain can vary to such an extent that it doesn’t work.”

Jason Gill, a senior scientist at the center for phage technology at Texas A&M University in her statement said that it could be an option against antibiotic resistance, but won’t work for everyone:

It’s probably going to turn out that the phages are going to be really effective for some conditions, and others they won’t work that well.”

Despite this, the medical and scientific communities are inspired. Professor Martha Clokie, from the University of Leicester, said in a statement:

I think that this work is enormously exciting. It shows how bacteriophages can be successfully developed as therapeutics even in very difficult circumstances where bacteria are resistant to many antibiotics and the bacteria are difficult to treat.”

“I think it will pave the way for other such studies to help with getting the necessary trials carried out on bacteriophages so that they can be used more widely to treat humans,” he said.

‘An opportune time for basic researchers’

The new study is supported by several previous research papers which have explored the potential of phage therapy.

For example, Kaitlyn Kortright from the Yale School of Medicine and colleagues recently published a review article in the journal Cell Host Microbes. The review, which was titled, “Phage Therapy: A Renewed Approach to Combat Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria”, examined the history of phage therapy research in Western countries. The researchers concluded the research, saying “phage therapy like any medical treatment, has benefits, costs, and limitations in usefulness that merit close scrutiny”.

They finish by saying, “this is an opportune time for basic researchers, clinicians, and physicians to work together to address open questions through rigorous experiments in the laboratory, in vivo models, and clinical cases to reward phage therapy with the renewed interest and greater examination that it deserves”.

Fernando Altamirano and colleagues from the School of Biological Sciences, Monash University say that now is the time for the “rebirth” of phage therapy as part of the “multidimensional strategies to combat antibiotic resistance”. In a recent review, published in in the journal Clinical Microbiology Reviews, the team writes that antibiotic resistance is one of the biggest public health problems today.

The therapeutic use of bacteriophages, viruses that infect and kill bacteria, is well suited to be part of the multidimensional strategies to combat antibiotic resistance.”

They explain that this concept was discovered almost a century ago and was overshadowed by the discovery of antibiotics. With rise of antibiotic resistance, there is soon to be a “rebirth” of these agents.

Journal reference:

Engineered bacteriophages for treatment of a patient with a disseminated drug-resistant Mycobacterium abscessus. DOI:10.1038/s41591-019-0437-z.