In 2018, Chinese scientist He Jiankui defied the law and scientific consensus by boldly editing the CCR5 gene in a human embryo, expecting to confer lifelong HIV resistance. The pregnancy eventually ended in the birth of two baby girls. Now the experiment appears to have gone seriously wrong, perhaps shortening their lives.

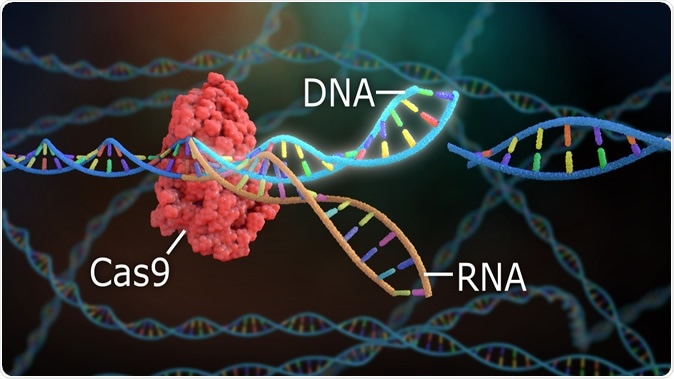

Using the powerful gene-editing tool called CRISPR/Cas9 on a human embryo to cut and insert new DNA, Professor He changed the original CCR5 gene in the embryo to a mutated version called Delta32. A similar mutation is naturally present in about one in ten individuals of European origin, who are resistant to HIV infection.

3D Rendering Crispr DNA Editing. Image Credit: Nathan Devery / Shutterstock

The CCR5 gene expresses itself as a cell surface protein on certain types of immune cells, providing the portal for HIV entry into the cell. Blocking this gene’s function essentially prevents HIV infection, theoretically prolonging life.

New research at the University of California, Berkeley, suggests that, to the contrary, when both copies of this gene are disabled, the lifespan is actually likely to be shortened by 1.9 years on average.

The researchers who brought out this study, published in the journal Nature Medicine, analyzed data on DNA and causes of death in over 400 000 British volunteers from the UK Biobank. What they found was shocking – without at least one functioning CCR5 gene, there was a 20% drop in the lifespan.

In other words, such individuals were 20% less likely to live up to the age of 76 years.

This is probably because they are more prone to other more common illnesses like West Nile virus and influenza.

The scientists also noted that fewer than expected numbers of people with this mutation were registered in the data bank, possibly because they were more likely to have died earlier than the general population.

Geneticist David Curtis of University College, London, commented: “There are many other examples in medicine where an intervention intended to treat one condition inadvertently causes major unexpected problems elsewhere."

The experiment provoked national scientific and governmental outrage, with China closing down He’s gene-editing activity in November 2018, citing serious violation of legislation and of medical ethics. The foremost concern in the minds of most scientists was the lack of data on the overall importance and role of the CCR5 gene to human life.

An earlier study published this year in the journal Cell indicated a possible link between this gene and brain function as well as with immunity. In other words, many genes have multiple functions apart from the ones we already know about, and tinkering with just one gene may affect the life system in many unexpected and even lethal ways. As Rasmus Nielsen, who led the new study, points out, “We know it has many different effects. The question is: Is it overall beneficial or detrimental to have this mutation? That was not known.”

In the light of current findings, he further notes: “It is probably not a mutation that most people would want to have.”

CRISPR has stolen the limelight in the gene editing field with its simplicity, power, precision and cheapness. However, this has also led to the unwarranted expansion of its use without the required stringent guidelines, as in Professor He’s experiment.

A few geneticists are in favor of human gene-editing, arguing that all new technologies have unknown cons when first introduced. They feel that attention should be focused on the risk-benefit ratio rather than on gene-editing technology, per se.

This kind of defense worries other scientists who fear that using the technology too early in its lifecycle will produce harm rather than good. Many studies have already produced initial evidence that CRISPR is not as precise in its effects as previously thought, and may cause collateral damage to other genes.

In addition, its use may reduce the immune defenses against cancerous changes in cells.

Gene editing, or genetic modification, introduces changes which are then passed down from generation to generation, to potentially influence the entire pool of human genes. We could actually be creating uncontrollable and incurable diseases far down into the future, because we don’t yet know all the effects of these gene changes.

This is one primary reason why scientists have generally stayed away from the use of this technology in embryonic humans so far.

The take-home? It’s not yet time to edit genes in people, since we simply don’t know enough about all that each gene does. “Introduction of new or derived mutations in humans using Crispr technology... comes with considerable risk even if the mutations provide a perceived advantage," the study authors sum up.

Sources:

- The hidden cost of genetic resistance to HIV-1, JO, Nature Medicine, AB, 1546-170X, UR, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-019-0481-8, DO - 10.1038/s41591-019-0481-8, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-019-0481-8

- CCR5 Is a Therapeutic Target for Recovery after Stroke and Traumatic Brain Injury, Mary T. Joy, Einor Ben Assayag, Dalia Shabashov-Stone, Alcino J. Silva, Esther Shohami, S. Thomas Carmichael Cell, VOLUME 176, ISSUE 5, P1143-1157.E13, FEBRUARY 21, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2019.01.044, https://www.cell.com/cell/fulltext/S0092-8674(19)30107-2#secsectitle0020