Even as Australia reels under a deadly flu season, some solace may be found in the fact that almost 95% of of five-year-old Australian children are almost completely immunized against deadly childhood diseases, according to the latest report.

Globally, vaccine coverage has reached about 85%, making this a remarkable achievement which deserves emulation at all levels.

Vaccine-preventable childhood killer diseases covered by the standard include diphtheria, polio, pertussis, tetanus, and the virus that causes infant meningitis, Hemophilus influenza type B, as well as the hepatitis B virus. Other vaccines included in the program include the mumps, measles and rubella viruses.

Virus Cell attacks immune system cells. Image Credit: Explode / Shutterstock

Universal childhood immunization

Universal childhood immunization is widely promoted as a simple, safe and effective way to prevent these diseases in children before they are exposed to them. Immunization works not only by protecting the individual who receives the vaccine, but also by inciting a phenomenon called herd or community immunity. This is defined as the production of resistance to the spread of communicable diseases within a population by the presence of immunity to the disease concerned within a very high percentage of individuals within the population. Thus immunization helps the whole population once coverage rates achieve and are maintained at a sufficiently high level.

Community immunity confers a type of protection that is especially important for newborn babies, older people, those on chemotherapy, those with weakened immunity, and those who are sick and cannot be immunized, but are at increased risk of infection. However, herd immunity does not protect the individual against vaccine-preventable diseases as effectively as immunization does, and should not be promoted as an alternative to being immunized.

All vaccine-preventable diseases cannot be protected against by herd immunity, as tetanus, for instance, comes through environmental spores of the tetanus bacillus rather than from other people. For these illnesses, individual immunization is the only way to ensure the child is protected.

How immunization works

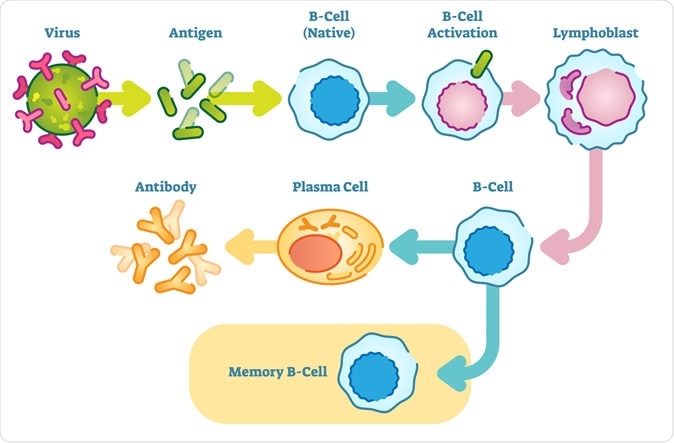

Immunization works by presenting a weakened form of the molecules on the virus or bacteria that produce these illnesses to the body before it is exposed to the actual germs. The presence of these molecules, called antigens, induces an immune reaction in the body, which manifests as slight fever, tenderness and other mild local or systemic reactions. This is followed by the storage of the memory of this antigen data within the immune system, inside the memory cells, or B-lymphocytes.

When faced with this infection again, the body quickly kicks into a highly specific and powerful defense mode, as the B-lymphocytes that store the relevant information multiply and transform into antibody factories. These churn out specific antibodies, protein molecules that recognize and bind to the antigen on the specific bacteria against which the body was immunized. The bound antibody helps the other immune cells to rapidly neutralize and destroy the invading microbes and contain the infection before the person become sick. In most cases the individual is totally unaware even of having been exposed to the infection, because of the speed and effectiveness of the immune reaction.

B cells, also known as B lymphocytes, are a type of white blood cell of the lymphocyte subtype. They function in the humoral immunity component of the adaptive immune system by secreting antibodies. Image Credit: VectorMine / Shutterstock

Australian model: worthy of emulation

The quarterly data from Australia shows that close to 95% of children who are five years old have received full immunization this year. The coverage is even higher, at almost 97%, among indigenous children at five years of age. Victoria and Tasmania are regions with exceptionally high rates of full immunization. More and more children are being fully immunized at one, two and five years all over the country.

The importance of this uniform pattern of coverage is best appreciated when compared with countries like the UK, which have high rates of immunization on a national basis, but with significant pockets of poor immunization coverage. This leaves plenty of room for contagious diseases to spread and produce local or regional outbreaks, as happened with measles in 2013, in Wales. This is because a no-immunized person in these areas who is exposed to measles, for instance, is likely to come into contact with many more non-immunized people and to pass on the disease.

Australian federal health minister Greg Hunt commended the results, saying, “The latest figures show that the vast majority of parents are hearing the message about the benefits of vaccinations and I am delighted that our public health campaigns and our immunization programs are protecting all Australians.”