From this September, boys of 12 and 13 will receive the HPV vaccine in all UK schools, hopefully preventing mouth, throat, penile and anal cancers caused by this oncovirus.

This occurs 11 years after a similar program for girls. The whole HPV vaccine program is now expected to prevent more than 100,000 cancer cases by 2058. This includes over 64,000 cervical cancers, almost 20,000 other cancers in women, and 30,000 cancers in men.

The HPV or human papilloma virus causes genital warts, precancerous cervical lesions, and cancers in various regions of the body. It exists in about 150 strains, and easily transmitted by sexual contact, including kissing. It is the most common sexually transmitted infection in the world, affecting 79 million people in the U.S. alone. While in over 90% of cases it is cleared naturally from the body, a few strains are capable of persistence and transformation of skin cells into genital warts and cancers of the uterine cervix, as well as of the head and neck. The virus causes about 5% of cancers globally. In the US, National Cancer Institute statistics link 3% of cancers in women and 2% in men to HPV.

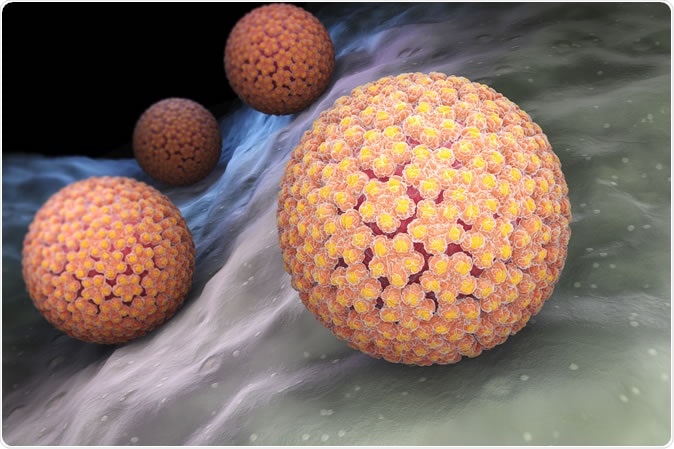

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is a DNA virus from the papillomavirus family. 3D illustration - Credit: Tatiana Shepeleva / Shutterstock

10 million doses of vaccine have been distributed to cover 80% of UK women between 15 and 24 years against HPV so far. According to Public Health England (PHE), infections with high-risk HPV 16/18 strains in women between 16 and 21 years have declined by 86%, while in Scotland, experts say precancerous lesions of the uterine cervix have decreased by 71%. Vaccination of boys is bound to further prevent cervical cancers in women by increasing the overall number of immune people in the population, making it more difficult for the virus to spread from person to person. This is known as community immunity.

PHE head of immunization Mary Ramsay urged that all children eligible for the program accept the vaccine as soon as possible. She stated: “This universal program offers us the opportunity to make HPV-related diseases a thing of the past and build on the success of the girls' program.”

"Offering the vaccine to boys will not only protect them but will also prevent more cases of HPV-related cancers in girls and reduce the overall burden of these cancers in both men and women in the future.”

The vaccine needs to be taken early, at 11-13 years, before sexual activity begins, as it is not as effective in later adolescence, and a second dose is necessary for full immunization. This second dose is typically given 6-24 months after the first.

The vaccine acts to produce a much stronger immune reaction than the virus would, according to Professor John Doorbar of Cambridge. The protection lasts at least 10 years according to global research, but could even be lifelong, says PHE.

Few countries offer HPV vaccine to boys, but the US is among them, with the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommending its use for both males and females before the age of 26 years. This statement last month extended previous recommendations for women to be immunized up to 26 years, but men up to 21.

Australia was the first to introduce nationwide HPV immunization. It has been offering the HPV vaccine to girls since 2007, and to boys since 2013. This has reduced HPV infections in young women from 22% to 1%, and the incidence is dropping in boys too. Experts say that this means it will be free of the infection within two decades.

Arne Akbar, who heads the British Society for Immunology, commented that this measure would build on the already successfully running girls’ immunization program to extend the protection against HPV-related cancers to boys as well. He said, “We encourage parents of eligible boys and girls to take up the offer and protect future generations against these preventable diseases with the HPV vaccine.”

Despite its many benefits, and regardless of the fact that the HPV vaccine has been declared to be safe by the WHO and the U.S. CDC, as well as by a large Norwegian study, several researchers have drawn attention to the small but significant number of immunized people who have reported neuropathic pain syndromes, such as chronic regional pain syndrome. The fact that four years later, the vast majority (93%) of this group remain incapacitated, has led to concern among researchers that adverse effects of the vaccine be properly evaluated before mass immunization programs. Adverse effects may be more common in certain genetic backgrounds, and experts have suggested that this should be properly researched to offer predictive markers that can help decide individuals decide on vaccine use.

Journal references:

- Segal Y. et al., (2018). Vaccine-induced autoimmunity: the role of molecular mimicry and immune crossreaction.. Cellular and Molecular Immunology. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2017.151

- Cervantes J. L., et al., (2018). Discrepancies in the evaluation of the safety of the human papillomavirus vaccine. Memorias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. https://dx.doi.org/10.1590%2F0074-02760180063

- Feiring B. et al., (2017). HPV vaccination and risk of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis: A nationwide register-based study from Norway. Vaccine. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.06.031

- Martinez-Lavin M. et al., (2017). Serious adverse events after HPV vaccination: a critical review of randomized trials and post-marketing case series. Clinical Rheumatology. doi: 10.1007/s10067-017-3768-5