Researchers from University of California, Irvine have found the key responses of brain cells to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and say that this could help them understand the chronic debilitating and progressive neurodegenerative disease better in future. They developed a unique mouse model containing human brain microglial cells in order to study the real life functions and movements of these cells in response to AD.

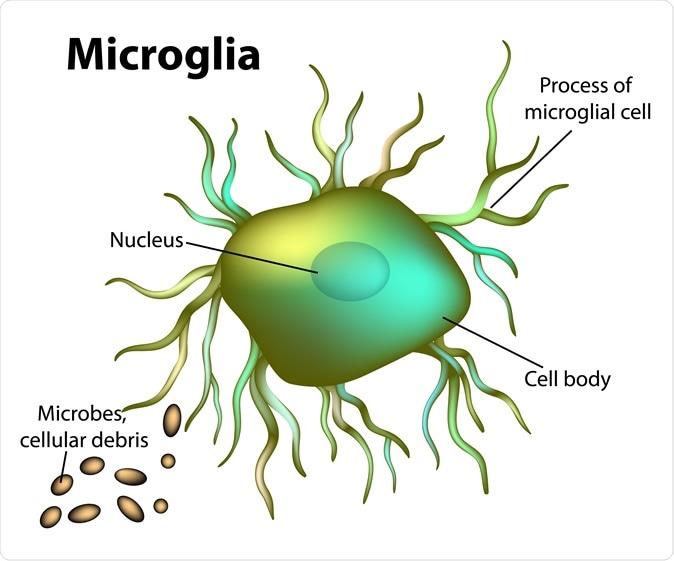

Microglial cell. Image Credit: Sakurra / Shutterstock

The team used the human brain cells or the microglia and allowed them to multiply and function within mice brains. Lead researcher Mathew Blurton-Jones, associate professor of neurobiology and behaviour, explained that this approach has shown them the cellular mechanisms that occur and contribute to AD. This study could also help researchers working with Parkinson's disease, stroke recovery and recovery from traumatic brain injury says Dr. Blurton-Jones. The results of the study were published in the latest issue of the journal Neuron and is titled “Development of a Chimeric Model to study and manipulate human microglia in vivo”. Blurton-Jones is also a member of the Sue & Bill Gross Stem Cell Research Center and UCI MIND.

The reserchers, led by Mathew Blurton-Jones, associate professor of neurobiology & behavior, said the breakthrough also holds promise for investigating many other neurological conditions such as Parkinson’s, traumatic brain injury and stroke. UCI

The researchers explain that it took nearly four years of intensive research to develop these special “chimeric” mice that contained the human microglial cells in their brains. The team used pluripotent stem cells, or iPSCs and coaxed them to become the young microglia. Pluripotent cells are stem cells that could be turned into any cell type within the body. These young microglia developed from human pluripiotent cells were then implanted into the genetically-modified mice. After several months the mice were examined and it was seen that 80 percent of the microglia within their brains were of human origin. The word “chimera” comes from Greek mythology that indicates a composite animal with different parts or cells from different animals. The Greek chimera monster was a fire-breathing lion like creature with the head of a goat seen on its back and a tail with a snake’s head on it. These human microglia containing mice were termed “xMGs”.

Blurton-Jones said, “Microglia are now seen as having a crucial role in the development and progression of Alzheimer's. The functions of our cells are influenced by which genes are turned on or off. Recent research has identified over 40 different genes with links to Alzheimer's and the majority of these are switched on in microglia. However, so far we've only been able to study human microglia at the end stage of Alzheimer's in post-mortem tissues or in petri dishes.” This means that the live mice with human microglia provided an ideal model to study the deeper workings of AD, he explained. Earlier they tried their experiments with mice microglia and because of the species specific differences, their results could not be replicated in humans, write the researchers.

Jonathan Hasselmann, one of the two neurobiology & behavior graduate students involved in the study also explained, “This specialized mouse will allow researchers to better mimic the human condition during different phases of Alzheimer's while performing properly-controlled experiments.” Neurobiology & behavior graduate student and study co-author Morgan Coburn added, “In addition to yielding vital information about Alzheimer's, this new chimeric rodent model can show us the role of these important immune cells in brain development and a wide range of neurological disorders.”

Next the team began to check if these human microglia would react to amyloid plaques within the mice brain. Amyloid plaques are protein clumps that are typically seen in patients with AD, They tend to accumulate and slowly cause the cognitive decline and memory loss in these individuals. The researchers found that in these mice, the microglia migrated towards the amyloid plaques as they had expected.

The team wrote, “Most notably, transplanted microglia exhibit robust transcriptional responses to Aβ-plaques that only partially overlap with that of murine microglia, revealing new, human-specific Aβ-responsive genes.” This meant, explained researchers that the human microglia within the mice showed similar changes and responses to amyloid plaques as would be seen in humans with AD. In response to these plaques the microglial protein transcription processes are often triggered explained researchers. This study has also revealed certain genes in the microglia of humans that respond to the signals sent by the plaques found the researchers.

Blurton-Jones said, “The human microglia also showed significant genetic differences from the rodent version in their response to the plaques, demonstrating how important it is to study the human form of these cells.” The team concludes, “We therefore have demonstrated that this chimeric model provides a powerful new system to examine the in vivo function of patient-derived and genetically modified microglia.”

Source:

Journal reference:

Development of a Chimeric Model to Study and Manipulate Human Microglia In Vivo, Jonathan Hasselmann, Morgan A. Coburn, Whitney England, Dario X. Figueroa Velez, Sepideh Kiani Shabestari, Christina H. Tu, Amanda McQuade, Mahshad Kolahdouzan, Karla Echeverria, Christel Claes, Taylor Nakayama, Ricardo Azevedo, Nicole G. Coufal, Claudia Z. Han, Brian J. Cummings, Hayk Davtyan, Christopher K. Glass, Luke M. Healy, Sunil P. Gandhi, Robert C. Spitale, Mathew Blurton-Jones, doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.07.002, https://www.cell.com/neuron/fulltext/S0896-6273(19)30600-2