It’s not just about garlic on the breath any more; your breath could now help reveal a variety of diseases. The science behind it is that the human body excretes a number of volatile compounds through the breath, and the type and proportion of these vary with the kind of disease. For instance, diabetes, lung cancer, and Parkinson’s disease all produce distinct molecules called disease biomarkers in the breath. These can be measured, but it took a while to develop instruments capable of detecting these compounds. Now, however, a very sensitive device has been reported for the detection of the common molecule ethanol, and is dubbed the “sniff-cam”.

Ancient times saw much greater reliance on the five bodily senses to diagnose disease in others. This sensitivity to the variations that occur in the body in health and disease has largely been lost as we came up with increasingly sophisticated devices to measure various aspects of physiological functioning. Among these is the modern breath-based detector, which works on the principle of biofluorometric imaging.

The fact is that certain volatile organic compounds (VOCs), which simply refers to odorous biochemical molecules, are synthesized in the healthy human body. Their levels are dependent on several other factors like body mass and sex, which means multiple criteria must be considered to make a diagnosis based on these compounds.

With modern technology the ability to carry out such advanced computations has led to the development of such detectors. The current report unveils one such device which is designed to detect the VOC ethanol, found commonly in all types of glucose fermentation products including wine and hard liquor. This alcohol is one which is produced even in a non-drinker by the bacterial flora that live in the mouths and guts of human beings, and which consume glucose. However, older instruments to detect ethanol at these low concentrations were not only large but also costly, and the operators required professional training to achieve good results.

A team of scientists led by Kohji Mitsubayashi produced a detector that was able to pick up VOCs like acetone, which occurs as a result of fat breakdown in the body. This device was called the “bio-sniffer”. Following this successful innovation, they worked on developing the earliest sniff-cam. This latter device could detect ethanol released from the skin of a person who had ingested alcohol using imaging technology. The team was dissatisfied with the sensitivity of the device, and continued to work on further ways of increasing its sensitivity so that it was capable of detecting biomarkers present at diagnostic levels.

The newest form of the “sniff-cam”, presented in the current report, is a gas-imaging system which is very sensitive for gaseous ethanol.

Ultrasensitive Sniff-Cam for Biofluorometric-Imaging of Breath Ethanol Caused by Metabolism of Intestinal Flora

The first clinical test of the new sniff-cam has been tested on a group of males who had neither eaten nor drunk. It was able to pick up tiny amounts of ethanol from their breath at an average of 116 ppb. This shows its ability to detect VOCs at concentrations which were 25 times lower and spread over a much wider range of concentrations than older versions or devices.

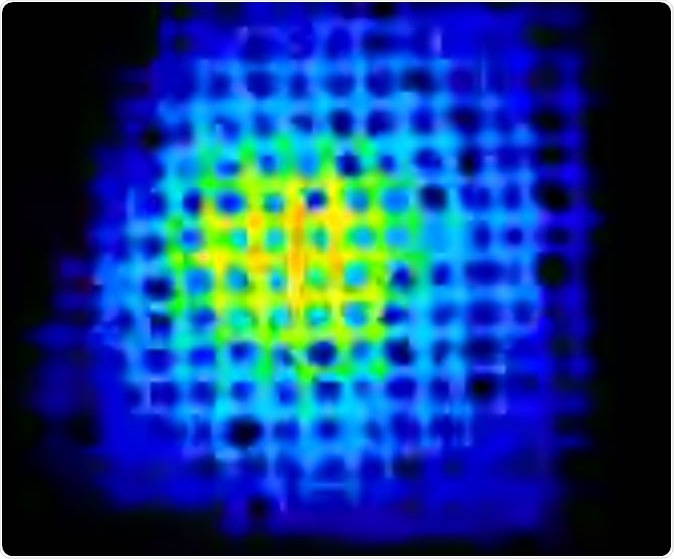

The revolutionary sniff-cam comprises an ultraviolet light-emitting diode (LED) which acts as a source of excitatory light in the form of a ring, mounted around the lens of a camera. This set-up allows the target molecule to be excited and imaged at the same time.

In this reaction, ethanol reacts with oxidized NAD (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide), an electron carrier molecule, on a mesh of alcohol dehydrogenase enzyme molecules. The use of the enzyme in immobilized form on a mesh is a concept carried over from the earlier version. The mesh is soaked in oxidized NAD and located in front of the camera.

When the mesh is exposed to gaseous ethanol, the result is that the enzyme breaks down the alcohol, simultaneously reducing the NAD. The NADH gives off fluorescence form, emitting light at 490 nm after it is excited by light at 340 nm. The emitted fluorescence is immediately captured by the camera. This means that the concentration of ethanol in the gas is displayed in terms of the intensity of fluorescence emitted by the image analysis system was also upgraded to allow the detection of even minute amounts of ethanol.

The development of this highly sensitive detector is expected to pave the way for further exploration of the types of scent molecules that are emitted by the body in a range of disease conditions.

Journal reference:

Ultrasensitive Sniff-Cam for Biofluorometric-Imaging of Breath Ethanol Caused by Metabolism of Intestinal Flora, Kenta Iitani, Koji Toma, Takahiro Arakawa, and Kohji Mitsubayashi, Analytical Chemistry Article ASAP, DOI: 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b05840, https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.analchem.8b05840