For decades, doctors have known that gallstones assemble and grow from cholesterol and calcium crystals as the salts accumulate and stick together in bile – the yellowish-brown fluid that helps break down lipids in the small intestine. However, one hurdle that researchers have been unable to overcome in the development of new treatments is that they have not known how the calcium and cholesterol crystals stick together to form the stones.

Now, Martin Herrmann at the Friedrich–Alexander University Erlangen–Nürnberg in Germany and colleagues have found that immune cells called neutrophils seem to be involved. The neutrophils generate sticky webs of DNA called neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) that act as a “glue” and bind the crystals together during gallstone formation.

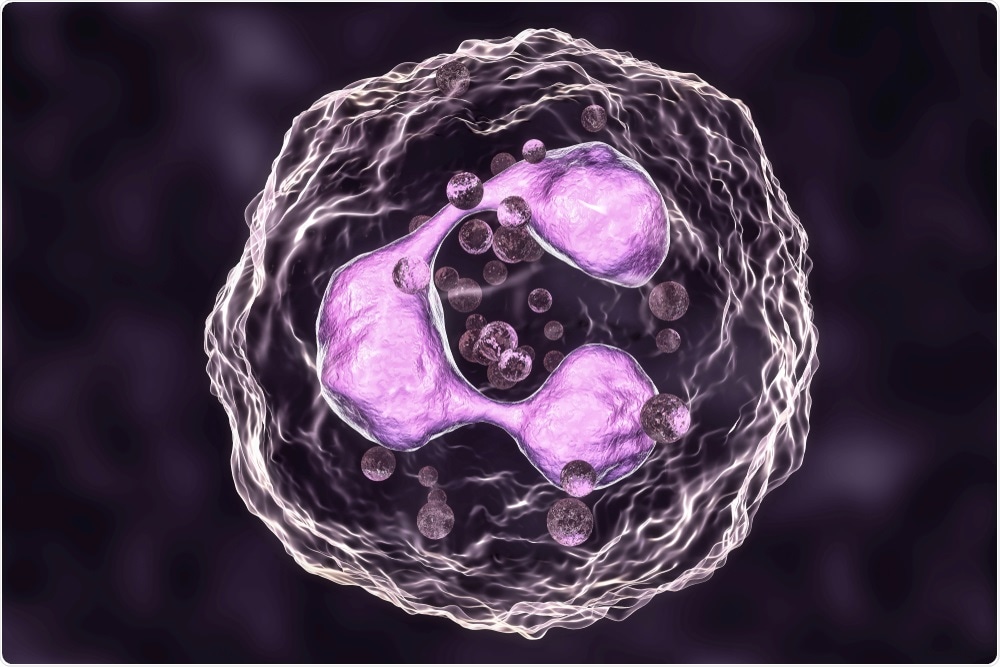

Kateryna Kon | Shutterstock

Kateryna Kon | Shutterstock

Gallstones affect an estimated 25 million Americans and are a leading cause of hospital admissions worldwide. The stones form in the gallbladder, which secretes bile via the bile ducts to help break down fat in the small intestine. They may be as small as a grain of sand or may grow to the size of a golf ball.

Although the majority of gallstones do not cause symptoms, they can pass into the small intestine or block a bile duct, causing severe abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, infection and even death.

Surgical removal of the gallbladder is one of the most common operations performed among adults in the US. Medicines are available, but they can take months or years to break up the stones. The current discovery potentially provides a starting point for developing new, more effective treatments.

Examining the composition of “gallbladder sludge” to find the mystery glue

Herrmann and colleagues made the discovery while studying gallstones found in the bile of people undergoing surgery to receive stents. They extracted and examined the composition of a substance referred to as “gallbladder sludge,” which is made up of small stones in the bile.

The researchers found large aggregates of neutrophil DNA on the surface of the small stones, as well as activity of an enzyme called neutrophil elastase that breaks down proteins. They also found the clumps of DNA and evidence of high neutrophil elastase activity on the surface of larger stones.

Neutrophils are thought to be the first responders that protect the body against infection. By extruding the web-like NETs, they catch and destroy microbes that lead to infection.

The DNA and molecules found on the surface of the gallbladder sludge belonged to NETs, a tell-tale sign that the neutrophils had been targeting bile crystals.

Neutrophils eject their DNA to “hog-tie” cholesterol crystals

To find out what had triggered NET formation, the researchers cultured cholesterol crystals with human neutrophils, which caused the neutrophils to shoot their DNA out at the crystals.

To determine whether the NETs were involved with gallstone formation, the team mounted human gallstones on rotating, shaking devices and spun them in the presence or absence of neutrophils.

In the presence of neutrophils, the stone surfaces rapidly accumulated neutrophil DNA fragments and neutrophil elastase, which then pulled cholesterol and calcium crystals together to form even larger stones.

“When they find suspicious matter, for example, the crystals that form gallstones, they tend to eject their DNA and hog-tie the material,” says Herrmann.

When the team stopped the neutrophils from making NETs, the stones no longer accumulated the DNA, suggesting that this was stopping them growing.

Stopping gallstone growth in mice

Next, the researchers fed mice a cholesterol-rich diet known to promote gallstone formation. Some of the mice had a genetic defect that stops NET formation and those animals had fewer and smaller gallstones than healthy mice that had normal NET formation. Similarly, mice that had a lower blood neutrophil count also formed smaller gallstones than their healthy counterparts.

The researchers then added either a compound that inhibits an enzyme involved in NET formation to the diet or a beta-blocker that prevents neutrophil migration to the gall bladder. Both treatments completely blocked any additional growth of any pre-existing gallstones.

Paving the way for new prophylactic treatments

The findings could lead to preventative treatments for gallstones. The beta-blocker the team tested is already used to treat heart conditions and Herman suggests that trials be conducted to see whether the drug also helps to prevent gallstones.

Neutrophils have long been considered the first line of defense against infection and have been shown to generate NETs that entangle and kill pathogens. Here, we provide additional evidence for the double-edged-sword nature of these NETs by showing that they play an important role in the assembly and growth of gallstones. Targeting neutrophils and NET formation may become an attractive instrument to prevent gallstones in high-risk populations."

Martin Herrmann, Lead Researcher

Co-author Luis Muñoz agrees that human studies are now required to establish new therapies for gallstone disease: “Hopefully, we can convince pharmaceutical companies to perform a clinical study with inhibitors of NET formation or NET aggregation".

Journal reference:

Munoz, L. E., et al. (2019). Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Initiate Gallstone Formation. Cell. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2019.07.002