Merkel cell carcinoma is a rare and aggressive type of skin cancer. Also called neuroendocrine carcinoma of the skin, it is much less common than most other types of skin cancer. But, it’s one of the most dangerous types since it’s more likely to spread to the other parts of the body. Since the condition is very rare, affecting 2,000 people in the United States every year, little information is available on the genetic factors that contribute to the development of the illness.

A team of researchers at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute are starting to learn more about how Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) develops. They developed the largest descriptive genomic analysis of MCC patients and the data provides crucial information to better understand the disease process, and at the same time, open the doors for the development of new treatment approaches.

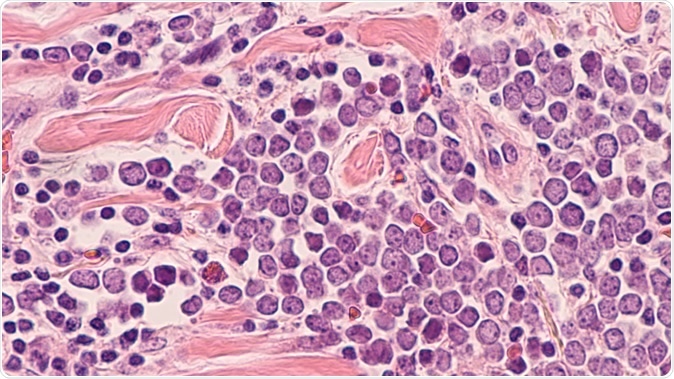

Microscopic image (photomicrograph) of a Merkel cell carcinoma, a highly aggressive type of skin cancer, derived from neuroendocrine cells, typically of the face, head or neck. - Image Credit: David Litman / Shutterstock

DNA mutations related to MCC

Published in the journal Clinical Cancer Research, the researchers have identified two distinct molecular subgroups, including ultraviolet light (UV)-driven subtype and a viral-driven subtype, both can be considered as important risk factors in the development of cancer.

Many patients with MCC manifest DNA mutations caused by exposure to ultraviolet radiation. This means that exposure to both natural and artificial sunlight may increase the risk of MCC. Subsequently, DNA and proteins from the virus Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) are present in many patients with cancer. Hence, the researchers found that these two factors may play important roles in MCC development.

To land to their findings, they performed comprehensive molecular profiling among 317 tumors from patients diagnosed with MCC. They also studied and evaluated oncogenic mutations, mutational signatures, tumor mutational burden (TMB), and the presence of Merkel cell polyomavirus. The patients were also profiled for 322 cancer-related genes.

In a group of 57 patients, the investigators conducted an analysis to evaluate for clinical and molecular correlates to immune checkpoint inhibitor response and disease survival.

New promise for MCC treatments

Before, there were only limited treatment options for patients with MCC. As a result, most patients incur poor prognosis and a 5-year survival rate of only 20 percent. The findings of the study could provide a new way to treat the tumor, possibly improving prognosis and the quality of life of the patients affected.

The new body of knowledge sheds light on MCC biology and disease process. In the long run, the study could help develop therapeutic advances in immunotherapy and analysis of patients to further understand the disease’s genetic landscape, since these could all affect treatment response.

Importantly, the investigators found that early treatment of patients with immunotherapy, the better the response to the treatment. In fact, in their study, 75 percent of patients who had immunotherapy responded to the treatment at the first try. However, when the treatment is given late, or during the second and third tries, the response rate reduced to 39 percent and 18 percent, respectively.

Understanding MCC disease

Merkel cell carcinoma is a rare type of skin cancer. It often develops in older people, and the known risk factors are long-term exposure to the sun and a weak immune system.

MCC is 40 times rarer than melanoma, affecting about 2,000 people in the U.S. each year. First, a person with MCC may notice a fast-growing and painless nodule on the skin. The color of the nodule may be red, blue, purple, or maybe skin-colored.

Cancer stems from changes in the Merkel cells, which are located deep in the top layer of the skin, called the epidermis. These cells are often connected to certain nerves, which are in charge of the touch sensation. Recent studies, however, say that the type of cancer may not originate directly from normal Merkel cells.

Though MCC is three times more likely to be deadly than melanoma, detecting cancer early is important for a better prognosis. Hence, determining new ways to treat the condition is crucial. Treatment becomes more difficult if the tumors have already spread to the other parts of the body. Early detection and treatment are important to improve survival rates.

Journal reference:

Knepper, T., Montesion, M., Russell, J., Sokol, E., Frampton, G., Miller, V., Albacker, L., McLeod, H., Eroglu, Z., Khushalani, N., Sondak, V., Messina, J., Schell, M., DeCaprio, J., Tsai, K., Brohl, A. (2019). The Genomic Landscape of Merkel Cell Carcinoma and Clinicogenomic Biomarkers of Response to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy. Clinical Cancer Research. https://clincancerres.aacrjournals.org/content/early/2019/08/09/1078-0432.CCR-18-4159