The human inner ear has a type of cell called the outer hair cell. These were thought to amplify sounds from the environment. However, a new study based on hearing in gerbils shows these cells are probably involved in regulating the sensitivity of the ear to sound. This could help find ways to preserve good hearing by protecting these cells from destruction.

How outer hair cells work

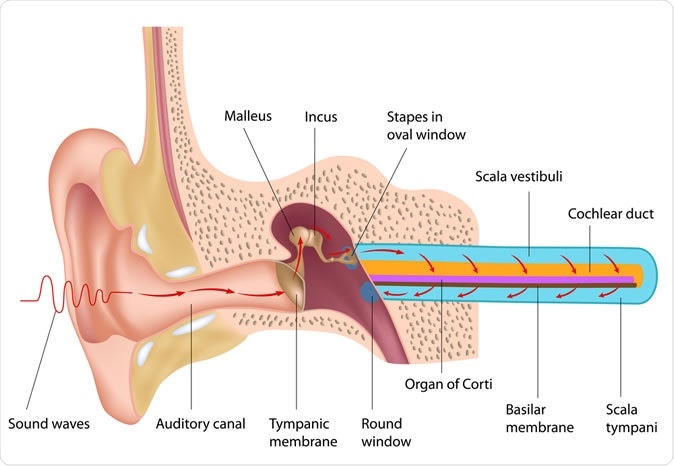

Mechanism of hearing - Illustration Credit: Alila Medical Media / Shutterstock

The ear has three zones, the outer, middle and inner ear. The inner ear contains hair cells which are tiny cells with protruding microscopic hair-like projections. They work somewhat like microphones, changing sound-induced vibrations into electrical nerve impulses that the brain translates into the sensation of sound, and simultaneously amplifying the signals before sending them on.

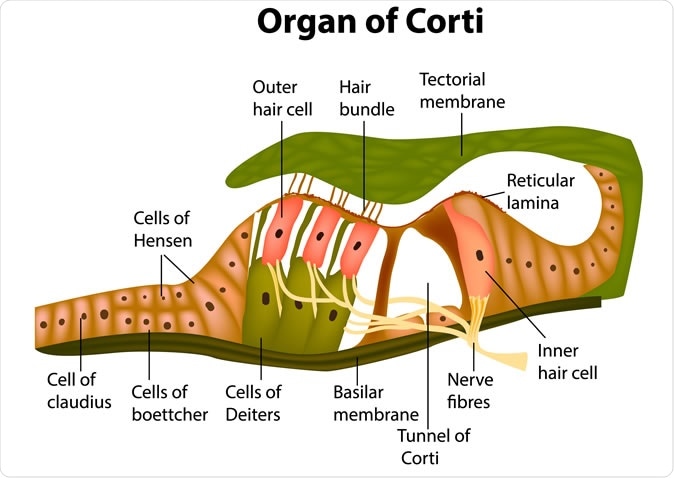

Structure of the organ of Corti. - Image Credit: Sakurra / Shutterstock

Both outer and inner hair cells have been found. The inner hair cells transmit signals to the brain while the outer hair cells modulate the sounds reaching the innermost part of the inner ear. Damage to outer hair cells results in significantly smaller vibrations being transmitted to the inner hair cells.

Outer hair cells are also found to have a property called electromotility. In other words, they change their length in response to electrical stimulation. This was thought to act as a mechanical amplifying function.

If this were their function, they would have to respond by length changes to individual waves impinging on the inner ear over the whole range of sound heard by the particular animal species, which can be as high as 150 kHz for some. This is especially the case with animals that hear sounds in the ultrasonic range, where the frequency is extremely high. However, their structure doesn’t go well with this theory: they are too big to vibrate sensitively in response to the high-frequency waves of high sounds in the range of individual cycles. Both electrical and mechanical issues exist that make this process non-feasible.

What does this study show?

In the current study, the researchers tried to resolve the question by using a technology called optical coherence tomography vibrometry (OCTV) to measure the corner frequency and the electromotility bandwidth in live gerbils. They used OCTV to measure the small movements that occur in the outer hair cells when the gerbils hear a sound. They used sounds between 13-25 kHz to test outer hair cell motility. They found that sounds up to about the middle of the top piano octave could elicit such movements, but beyond that, the cells could no longer move fast enough to keep pace. This is about 2.5 octaves below the range of frequencies required for ultrasonic hearing.

Automatic gain control function

The conclusion they reached was that the outer hair cells are quite similar to inner hair cells in their corner frequency, which doesn’t go beyond a few kHz. Thus they cannot amplify high-frequency ultrasonic sounds (which gerbils do hear quite well). Therefore this is not their function. Instead, rather than picking up and responding to individual sound waves, they act as envelope detectors. They can correctly pick up changes in the loudness of sounds and modulate them before passing them on to the inner ear. This protects the inner hair cells from extremely violent vibrations in response to very loud sounds. This is called automatic gain control and is used in numerous devices that receive and transmit sound waves to achieve dynamic range compression (DCR). This means loud sounds are toned down while quiet sounds are amplified, reducing the difference between the peak of the loudest sound and the trough of the quietest sound.

The advantage is that the overall loudness is perceived to be increased. In the present model the DCR in the cochlea is achieved by the automatic gain control function of the outer hair cells. In other words, the greater the excitation produced in the membrane of these cells by the sound vibration (as with louder sounds), the more the sound-induced vibration is toned down before passing it on to the inner hair cells. Researcher Anna Vavakou says, “Rather than amplifying sound, the cells seem to monitor sound level and regulate sensitivity accordingly.” This hypothesis is radically different from the current concept of outer hair cell function at present.

Knowing what outer hair cells do is very important, according to the study authors. These cells are vulnerable to antibiotics, loud noises and certain other drugs. This reduces hearing sensitivity. According to Marcel van der Heijden, “Figuring out their exact role could help guide efforts to prevent or even cure common forms of hearing loss.”

The study was published in the journal eLife Sep 24, 2019.

Journal reference:

The frequency limit of outer hair cell motility measured in vivo. Anna Vavakou, Nigel P Cooper, & Marcel van der Heijden. eLife 2019;8:e47667 doi: 10.7554/eLife.47667. https://elifesciences.org/articles/47667