A new study shows that infants in Bronze and Iron Age communities were fed milk using feeding vessels of clay. This report, appearing on September 25, 2019, in the journal Nature, shows the important place that animal milk has played in human food for thousands of years.

Why would we want to know if prehistoric babies also clutched their feeding bottles in their chubby little fists? Well, it tells us how older societies dealt with the challenges of repeated pregnancies and childbirth with small babies already in the house, as well as throwing light on infant illnesses. Older studies on the amount of nitrogen in bone collagen and dentine from infant teeth have thrown light on when babies were typically weaned. However, what did they give babies during this critical period? Not much is known.

Late Bronze Age baby bottles from Vösendorf, Austria.

Neolithic Europeans may just possibly have used clay feeding vessels for babies, and these become more common as we come to the Bronze and Iron Age civilizations. The use can be judged only by the shape, however; so these spouted vessels might just as well have been intended for use in feeding weak or sick people. However, the present study looks at ways in which the food contained in these vessels may be identified based on the composition of the fat residues.

The vessels themselves are small and have distinct spouts, and were found in the graves of infants of Bronze and Iron Age cultures. This suggests that they contained milk and were used to feed babies. This could have been a substitute for breastmilk or a supplementary feed, or a weaning food. However, it is plain that milk from cows or goats, or other domestic ruminants, was an important part of life in these societies.

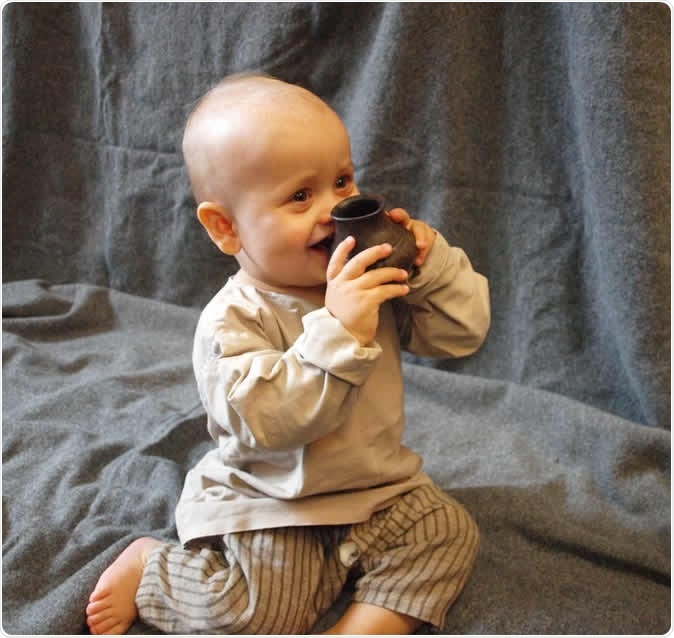

A modern-day baby testing a replica of one of the ancient bottles. Helena Seidl da Fonseca, Credit: Julie Dunne, University of Bristol

The bottles themselves range from simple pot-shaped vessels to elaborate kangaroo-shaped ones, each with a spout at the lowest portion. Dating back more than 7,000 years, they look deceptively like toys, except that they can all contain liquids without spilling when they are tilted, and have wide mouths, making them easy to clean. And of course, the spout, which betrays the fact that they are drinking vessels.

Feeding vessels of the late Bronze and early Iron Ages from Znojmo (Czech Republic), Harting (Bavaria, Germany), Franzhausen-Kokoron (Austria), Batina (Croatia) and Statzendorf (Austria), c. 1200-600 BC. Katharina Rebay-Salisbury, Credit: Julie Dunne, University of Bristol

The pottery originally belonged to the Neolithic period when animals were domesticated. Thus these societies had access to non-human ruminant milk to feed or wean infants. Ruminants include cows, sheep and goats. This discovery marks the first identification of definite food types used for infant feeding in prehistoric times.

‘Feeding bottles’ help unravel prehistoric secrets

The scientists analyzed the composition of the fats left in the old vessels, and found that they contained palmitic and stearic acids, characteristic of animal fat. They also showed the presence of short-chain fatty acids which are otherwise not usually found in old pottery, but are found in fresh milk. They then went on to analyze the isotopes in the supposed milk fats, and found that both breast and animal milk were present in the same container, indicating a mixture of these might have been used.

Another major revelation was the link between the introduction of animal milk as a baby feed and the increase in the number of babies that women had. Breastfeeding normally brings about a period of anovulation, or lack of egg production by the ovaries. This means that the woman normally doesn’t conceive during this time. However, this depends on very frequent breastfeeding, which doesn’t happen if the baby is also being fed animal milk.

Thirdly, if animal milk is used to substantially or completely replace human milk during very early infancy, it could serious affect the immune function of these babies, besides possibly failing to give them the nutrients they needed. However, when used at the right time to supplement nutrition, it could actually improve the babies’ health, as well as reducing the gap between babies. By enabling families to have more babies, this contributed to the rise in population around this time. Researcher Julia Dunne comments that this “ultimately led to the growth of cities and the rise of urbanisation that we see today.”

Fourthly, scientists ponder about something as mundane as bottle washing. How could these societies clean the bottles properly after feeding the babies? One archaeologist, who wrote an accompanying commentary, says, “These would have been really unsanitary to use and introduced all kinds of germs into the infant diet.”

The current archaeological interest in how the women and children lived in early societies comes a bit late, having begun just about a couple of decades ago. However, Halcrow continues, “Broadening our lens to include infants and children in the past is really important. They made up a high proportion of past populations. And if their health and experience is poor, that's obviously detrimental to society's function.”

Sources:

Journal reference:

Milk of ruminants in ceramic baby bottles from prehistoric child graves. J. Dunne, K. Rebay-Salisbury, R. B. Salisbury, A. Frisch, C. Walton-Doyle & R. P. Evershed. Nature (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1572-x. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-019-1572-x