Lyme disease is a dreaded disease caused by the bite of an infected tick. The only way to prevent it is by not getting bitten by the tick. However, this is not a practical recommendation, since even today about 300,000 thousand people are diagnosed with this infection, in the US alone, and over 100,000 in Europe, each year. Moreover, getting infected once doesn’t confer immunity against a repeat infection. Now, a plan to identify and accelerate the development of the most effective vaccine against this bacterium has been published in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases on October 17, 2019.

Lyme disease

Lyme disease is a potentially fatal condition caused by the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi, which is carried by certain ticks. The earliest symptoms are fever and headache, as well as a skin rash called erythema migrans. This occurs in up to 80% of infected patients, starting in about 3-7 days on average (but up to 30 days after infection), and spreading outwards to about a foot in diameter, sometimes showing a classic ‘target’ appearance of alternate light and dark rings.

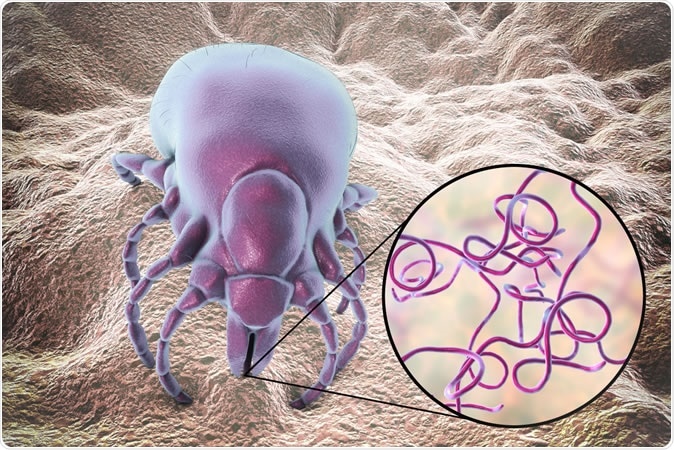

Lyme disease bacteria, Borrelia burgdorferi, transmitted by Ixodes tick, 3D illustration Credit: Kateryna Kon / Shutterstock

Late signs and symptoms occur more than 30 days after infection, and may include additional rashes, severe headaches with stiffness of the neck, joint pain and swelling, palpitations or irregular heartbeat, dizziness, breathing difficulty, nerve pain, brain or spinal cord inflammation, and tingling or shooting pains in the limbs.

Lyme disease can be treated adequately if diagnosed early, by taking the right antibiotics for a few weeks. However, untreated cases often develop joint complications, as well as spread of the infection to the heart and nervous system.

Prevention of contact

Currently, Lyme disease is preventable only by keeping skin out of direct contact with ticks, such as by wearing protective clothing and insect repellent, avoiding tick-infested areas, prompt removal of ticks and cutting down tall grass in areas used by humans.

Prevention by vaccination: an ill-fated pioneer

A very effective Lyme vaccine was made available in 1998 and enjoyed great success, with 1.5 million sales from 1998 to August 2000. However, biased reporting and fearmongering by so-called experts ensured that it was withdrawn from the market soon thereafter. Despite its undoubted efficacy of 80%, and an impressive safety record, unfounded public fears fueled by a bad press led to plummeting sales of the vaccine to about 10,000 doses in just four years , resulting in its discontinuation by the manufacturer in 2002.

Anti-vaccine publicity had won, and deprived the public of a valuable tool against Lyme disease – despite the fact that the open-access Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System (VAERS) only ever received about 900 reports of any kind of adverse event related to the Lyme vaccine, out of an incredible 1.5 million doses of vaccine administered over this short period.

Lyme disease incidence rates have doubled since then, however – and there is nothing left to prevent it, unless, of course, you happen to be a dog. A vaccine very similar to the discontinued human vaccine is still effective for dogs in tick-infested areas.

Now, however, after a hiatus of almost two decades, and many abandoned vaccine development efforts, a French manufacturer Valneva is bravely going ahead with a phase II trial of their multivalent vaccine.

New hope

Recently, several discussions have already taken place among researchers in this area, a recent meeting being at Banbury Center at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. These have already led to a number of diagnostic tests gaining FDA approval, which will help standardize the rates of infection. Continued conferences will help scientists decide on the right strategy to pursue to realize their goal of an effective vaccine. Up to this period, experts recommended a blood test-based diagnosis, with an initial enzyme immunoassay (EIA) followed by a western immunoblot assay for confirmation. The latest FDA approval now allows a second sensitive EIA to be used as the second step in diagnosis.

The new research concentrates on the two most promising technologies now under development to create a hybrid vaccine that is directed against the bacterium and the tick vector, thus preventing Lyme disease. The paper also reflects on how to communicate the need for the vaccine to the public, given that Lyme disease does not spread from person to person, and thus immunization does not prevent the disease in society as a whole. The researchers say, “"Lyme disease vaccination is an individual's personal choice. The concept of personal immunization should be part of public education and discussion.”

The current paper lays out expert opinion on the most favorable strategies for Lyme vaccine development. Says expert Rebecca Leshan, “Lyme disease has been a recurring topic for our meetings, and we're now seeing significant outcomes from those discussions. I expect the concepts laid out in the current paper will also have a real impact and help people at risk for Lyme disease."

Journal reference:

Maria Gomes-Solecki, Paul M Arnaboldi, P Bryon Backenson, Jorge L Benach, Christopher L Cooper, Raymond J Dattwyler, Maria Diuk-Wasser, Erol Fikrig, J W Hovius, Will Laegreid, Urban Lundberg, Richard T Marconi, Adriana R Marques, Philip Molloy, Sukanya Narasimhan, Utpal Pal, Joao H F Pedra, Stanley Plotkin, Daniel L Rock, Patricia Rosa, Sam R Telford, Jean Tsao, X Frank Yang, Steven E Schutzer, Protective Immunity and New Vaccines for Lyme Disease, Clinical Infectious Diseases, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciz872