A recent experimental study has shown that one reason for the occurrence of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) could be the deficit of a placental steroid hormone called allopregnanolone. The reason is that this hormone plays a critical role in the normal development of the brain in fetal life. When the hormone is suddenly no longer available, or its levels drop abruptly, the baby is more at risk of ASD. This study was presented on October 20, 2019, at the annual meeting Neuroscience 2019. The rate of ASD in the general population is about 1 in 60, at present, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Many previous studies examining the link between placental function and brain injury during development has looked at the possible role played by the disruption of oxygen delivery or of nutrients during this period. The current study is unique in its study of the role of allopregnanolone from the fetal placenta in brain development and the behavior of the affected individual over the long term. Researcher Claire-Marie Vacher says, “Our study finds that targeted loss of ALLO in the womb leads to long-term structural alterations of the cerebellum - a brain region that is essential for motor coordination, balance and social cognition - and increases the risk of developing autism.”

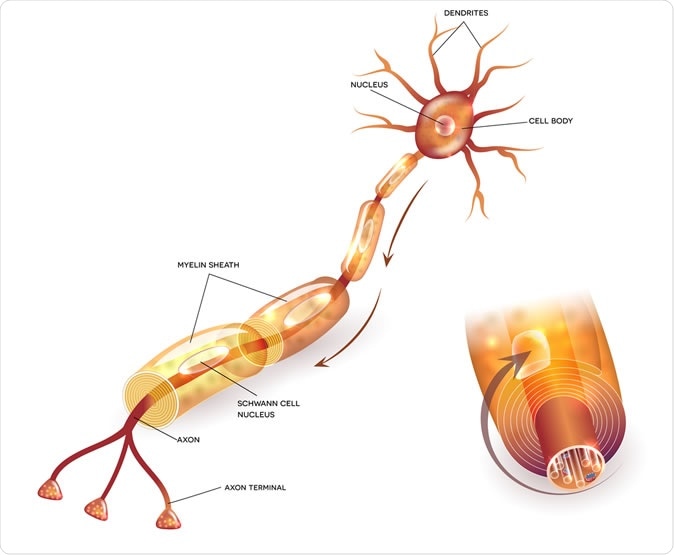

This is myelin, a lipid-rich insulating layer that protects nerve fibers. Image Credit: Tefi / Shutterstock

Allopregnanolone deficiency and the fetal brain

Allopregnanolone is a neurosteroid, that is, a steroid hormone that acts upon the brain. It is produced by the placenta throughout fetal development, but a significant rise first occurs in the second trimester. The highest levels occur towards full term.

In the current study, the researchers built a transgenic species for experimental purposes, in which one of the genes required for allopregnanolone synthesis was missing. Once the offspring was born, the scientists then monitored them for neurodevelopmental milestones. They found that these experimental offspring showed permanent changes in their neurologic and behavioral development. The changes were defined by the offspring’s sex and region.

In other words, the greatest degree of abnormal structural development was in the white matter of the cerebellum, which showed increased myelin layer thickness. However, the researchers note that the greatest behavioral disruption was in the field of repetitive behavior and significantly reduced sociable behavior, which are two of the key features in ASD.

The study also demonstrated that in this preclinical early model, at least, one injection of pregnanolone in the pregnant animal restored both cerebellar development and social behavior to normal.

Why allopregnanolone deficiency occurs

One major reason for a sudden deficiency of allopregnanolone activity in the brain is preterm birth – an eventuality that occurs in about 10% of infants. Preterm birth is defined as birth before 37 completed weeks of pregnancy. The importance of this phenomenon is seen in the fact that about 380,000 American infants are born preterm, putting them at risk for ASD and other neurodevelopmental disorders.

Again, hypertensive disorders such as preeclampsia, or pregnancy infections, can reduce the function of the placenta, and this may lead to loss of allopregnanolone production in a less dramatic but significant manner. This may finally cause lifelong deficits in neurological function.

Implications

The failure of placental function in early pregnancy may put the fetus at risk for long-term impairment because the placenta plays several important roles in neural development. For one, it supplies certain hormones critical for normal development and programming of the fetal brain. Secondly, it releases certain cellular chemical signals that prompt inflammation in the developing brain. Thirdly, an injured placenta is associated with increased fragility of the placental barrier, allowing toxic chemicals to have greater access to the forming neurological system.

In one or more of these ways, placental dysfunction may result not only in ASD-like symptoms but also in attention deficit disorder and psychoses such as schizophrenia. A better understanding of these links could help develop newer treatment methods to preserve brain function and prevent further injury.

The researchers now plan to concentrate on further studies to find the various roles played by the placental hormones in the development of the brain in the newborn and the fetus. Prior research by one of the researchers in the present study has shown that this is an exciting and vital field of study, which they call neuroplacentology.

Vacher says, “Our team's data provide exciting new evidence that underscores the importance of placental hormones on shaping and programming the developing fetal brain.”

Journal reference:

Placental programming of neuropsychiatric disease. Panagiotis Kratimenos & Anna A. Penn. Pediatric Research. 86, pages157–164 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-019-0405-9. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41390-019-0405-9#article-info