Ever heard of the lateral habenula? Very few, outside of neuroscience, probably have. Yet a new study, published in the journal Neuron, shows that characteristic changes in the way this area of the brain fires can result in a total loss of will to do anything – which is characteristic of one form of depression. This important finding could help scientists devise new methods of detecting these biomarkers and thus diagnose such individuals, as well as offer them more effective treatment.

Image Credit: Hikrcn / Shutterstock

A little about depression

Depression is the No. 1 mental illness worldwide. In the US, it strikes almost a tenth of the population every year. It is one of the leading reasons for lack of productivity at work. However, the symptoms of depression are surprisingly variable, shifting between loss of motivation, anxiety and anhedonia (the person’s inability to experience pleasure in any activity or object), making it a diagnostic challenge. Secondly, therapies for depression often don’t address the primary symptoms of the individual patient, leading to a one-size-fits-all approach that benefits few. For this reason, only about 50% of all people actually respond well to antidepressants and other medications for depression. Moreover, these have a lot of side effects.

This is why the new finding is so welcome – it could tell doctors if this particular symptom was present, giving them the opportunity to treat that particular feature in the patient. Says researcher Stephen Lammel, “If we had a biomarker for specific symptoms of depression, we simply could do a blood test or image the brain and then identify the appropriate medication for that patient. That would be the ideal situation. “

Mice, stress and depression

Mice have commonly been used to study the biological facets of depression for over 6 decades because of the classical symptoms of human depression produced in these animals by chronic stress – anhedonia, loss of motivation, and anxiety. Different mice show these symptoms in differing intensities, but so far researchers tended to club them together, irrespective of individual symptom.as a result, they would classify mice as either stressed (and therefore depressed) or non-stressed (and not depressed), without finer categorization by differential symptoms.

In the present research, the scientists wanted to find out how each symptom began, in terms of brain changes. This could offer the beginning of an explanation as to why different people with depression acted so differently and reacted to medication in such varying ways.

Why the lateral habenula?

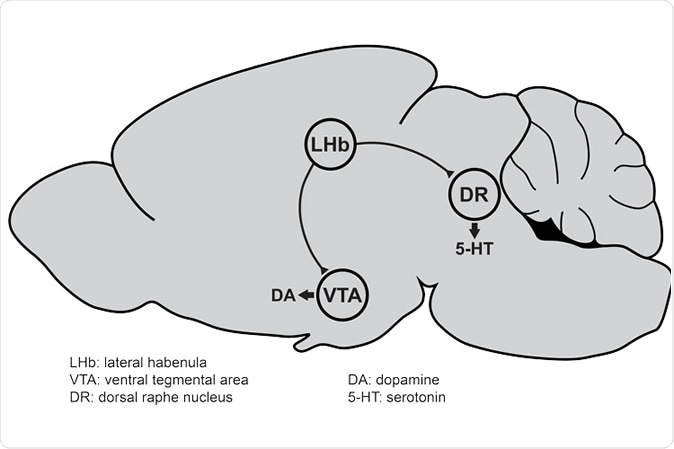

They chose the lateral habenula because of a small earlier study in which electrical stimulation of this region caused symptomatic improvement in patients with depression who failed to show a favorable response to other therapies. This area has been under the scanner in recent research because of its connectivity to other neurochemical systems, such as brain regions where neurotransmitters like dopamine and serotonin are produced. These, and similar molecules, are known to be part of the depression syndrome. In fact, most patients with depression receive serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs) to increase the level of serotonin in these areas, and thus elevate the mood.

Neurons in the lateral habenula (LHb) of the mouse brain send projections to the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and dorsal raphe nucleus (DR), two brain regions responsible for dopamine (DA) and serotonin (5-HT) release, respectively. Imbalances in dopamine and serotonin levels in the brain are associated with depression. (Image courtesy of Stephan Lammel)

In the current experiment, the researchers found that when the mice were exposed to chronic stress, the lateral habenula cells became excessively activated, firing off too many signals. However, this neural activity was associated only with marked reduction in behaviors that required motivation, rather than with anxious or anhedonic behavior. This was thus a marker for just one symptom of depression.

They then went on to look very carefully at the way the cells were firing, which cells were involved, how the connections were formed between the neurons, and the type of circuits that were operating – in response to long-term stress in the same mice that showed evidence of loss of motivation. This led to their collaboration with other scientists to result in the uncovering of overexpressed genes in this area in addition to cell-level alterations in neural function.

In other words, an increased level of expression of certain genes in the lateral habenula in response to chronic stress was associated with lower motivation levels. However, these genes are not linked to any other symptoms including anxiety or anhedonia.

Implications and future directions

The study is being followed up, to find out how deleting or partially suppressing these genes using CRISPR-Cas9 can help them distinguish those that are vital to this hyperactivity, and hence to the resulting lack of motivation. If they succeed, it could lead to the development of specific gene inhibitors that block these signals, restore normal activity to the lateral habenula cells, and bring back motivation to the affected mice.

In addition, they also want to see if they can detect any other signature changes accompanying other depressive features, notably anhedonia and anxiety. Their focus is on helping others in the field, both researchers and clinicians, see that depression is a umbrella term for a variety of disorders, and not just one illness. They emphasize the need for close communication and partnership between those in basic research and in clinical practice, since one can shape findings and actions in the other.

In Lammel’s words, “If we understand specifically how the brain changes in those animals with one certain type of symptom, there may be a way we can specifically reverse these symptoms. We think that our study could lay the foundation for guiding the development of the next generation of antidepressants that are tailored to specific depression symptoms.”

Journal reference:

Chronic Stress Induces Activity, Synaptic, and Transcriptional Remodeling of the Lateral Habenula Associated with Deficits in Motivated Behaviors Cerniauskas, Ignas et al. Neuron, https://www.cell.com/neuron/fulltext/S0896-6273(19)30778-0