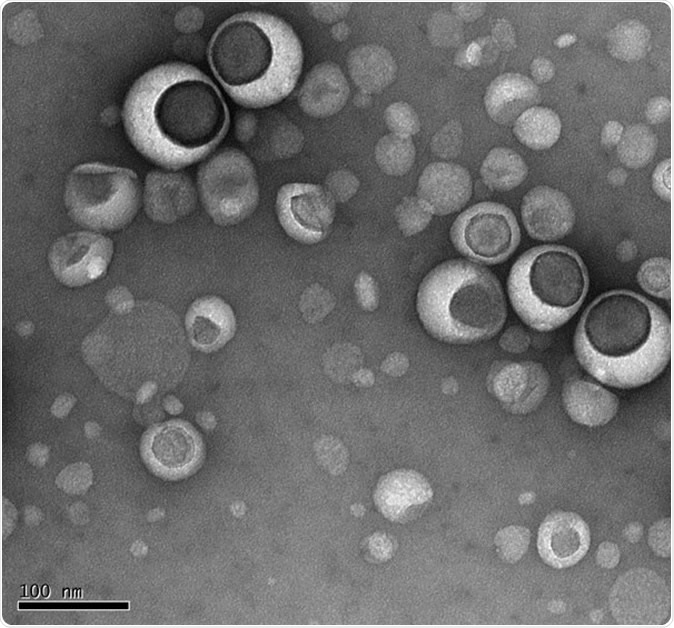

A new study from University of Manchester researchers, published in ACS Neuro, shows a high possibility of treating stroke patients using very small cell sacs called liposomes to bypass the blood brain barrier and carry lifesaving drugs to the brain to prevent damage following a stroke. These particles make pinheads look gigantic, being only 1/15,000 of their size at a diameter of 100 nm. Their small size and ability to make use of intrinsic transport pathways make them capable of passing the blood-brain barrier.

Lipsomes under electron microscope

The blood brain barrier

The blood brain barrier refers to a closely packed network of blood vessels with endothelial cells wedged tightly to form tight junctions, along with other types of cellular components such as the end feet of brain astrocytes, pericytes, microglia and a protein-based basement membrane. These combine to form a selectively permeable membrane or barrier that lets only some molecules make direct contact with the brain. It keeps even circulating blood and extracellular fluid away from the central nervous system. Only small molecules, molecules which dissolve in fat, and a few gases can pass freely through the blood vessel wall to reach the brain. Glucose can be actively transported across the barrier by specialized transport proteins designed for this purpose. The blood brain barrier therefore acts as a security system to keep out undesirable substances from the brain.

Why the barrier is important in stroke

The unforeseen problem with this immensely useful barrier is that it also prevents the treatment of stroke-damaged brain neurons by keeping out crucial drugs. Both the cells and the noncellular components pose immense challenges to the movement of drugs into the brain. At present, stroke can be treated only by clot-busters or by clot removal, within 4.5 hours of the stroke. There is no effective therapy to deal with the hundreds of damaging processes that continue to injure the brain cells thereafter, including oxidation and inflammation. If effective drugs could somehow get to the spot, they could change the course of events.

Liposomes

Liposomes, as the name suggests, are tiny sacs composed of lipids or fats, long chains of fat molecules, and are found in all living organisms. These small molecules have revolutionized treatment in cancers, skin and lung diseases as well as vaccine delivery ever since they were first discovered by the British blood specialist Alec Bangham, back in 1965.

Describing them as “a tried and tested method of delivering drugs to the body,” scientist Zahraa Al-Ahmady says, “They are easy to manufacture and used across the NHS. But our research shows that Liposomes have important implications for neurologists too.” These living nanoparticles have already been used to target tumors with anti-cancer drugs, increasing the local concentration of the highly toxic drugs while minimizing their impact on other healthy parts of the body.

The study

The new research used state-of-the-art imaging in a mouse model of stroke to visualize the transport of these drugs into the brain using liposomes. The scientists proved that the damage to the blood brain barrier caused by stroke allowed for the entry of liposomes, which made use of vesicles, or sacs, called caveolae, to get across the endothelial cells and penetrate the barrier. They could thus serve as drug carriers one day, once drugs are available to prevent and treat hypoxia in the brain cells. This is a key step in preventing further brain injury and limiting the consequences of a stroke.

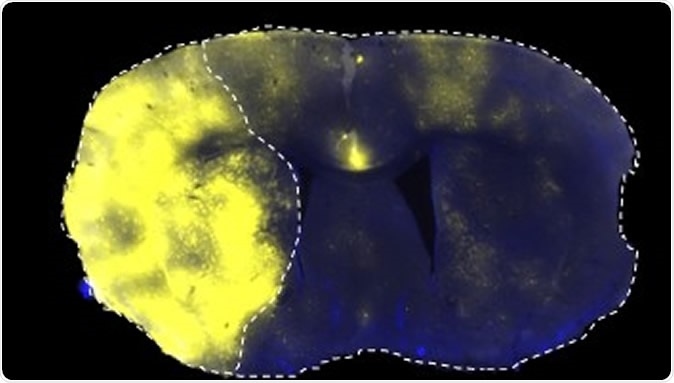

The scientists injected fluorescent liposomes into mice that had had a temporary cut-off of blood flow through a major brain artery, to mimic the effects of a stroke. The injections occurred at the following time points: 30 minute, 4 hours, 24 hours, and 48 hours from the time of circulatory cut-off. This was to study the early and late effects of the stroke on the passage of liposomes.

Fluorescently labelled liposomes selectively translocated into the stroke area left side of brain

The findings

The researchers found that liposomes accumulated in the ischemic brain after a stroke, taking advantage of the temporary disruption of the blood brain barrier. This breakdown of the cellular barrier occurs in a two-phase manner and is combined with a late breakdown of the paracellular barrier, composed of the basement membrane and other components. These blood brain barrier changes occur before acute neurological damage has set in.

The result is the long-term accumulation of liposomes within the affected area. These particles then enhanced neuronal repair processes after a stroke. Brain glial cells within the area of restricted blood flow also take up more liposomes selectively late in the course of the stroke, at 2-3 days.

The implications

This could be a marvelous opportunity for preventing potentially harmful late inflammatory responses, or to induce macrophage and microglial responses directed at brain repair. Thus liposomal entry at two time points indicate two separate opportunities to intervene in the brain stroke process, encouraging healing and repair.

Researcher Stuart Allan says, “The discovery that nanomaterials may be able to facilitate the treatment of stroke is exciting: scientists have long been grappling with the difficulties of treating brain injuries and diseases. The brain blood barrier is a major frontier in neurology, so the prospect of being able to cross it may have applications to other conditions as well - though clearly, much more work needs to be done.”

Calling it “an important milestone on the use of liposomes for yet another debilitating disease, such as stroke,” the researchers are clearly thrilled about the implications of their discovery.

Source:

Journal reference:

Selective Liposomal Transport through Blood Brain Barrier Disruption in Ischemic Stroke Reveals Two Distinct Therapeutic Opportunities Zahraa S. Al-Ahmady, Dhifaf Jasim, Sabahuddin Syed Ahmad, Raymond Wong, Michael Haley, Graham Coutts, Ingo Schiessl, Stuart M. Allan, and Kostas Kostarelos ACS Nano Article ASAP DOI: 10.1021/acsnano.9b01808, https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsnano.9b01808