The researchers found that infection with the malarial parasite triggered a strong inflammatory response, which in turn set off a powerful antibody response that cleared the parasite-infected cells. The intriguing thing is that malaria, chronic viral infections, and autoimmune diseases all share the same inflammatory signaling pathways, which suggests that this discovery could be exploited to improve treatment strategies for the latter as well.

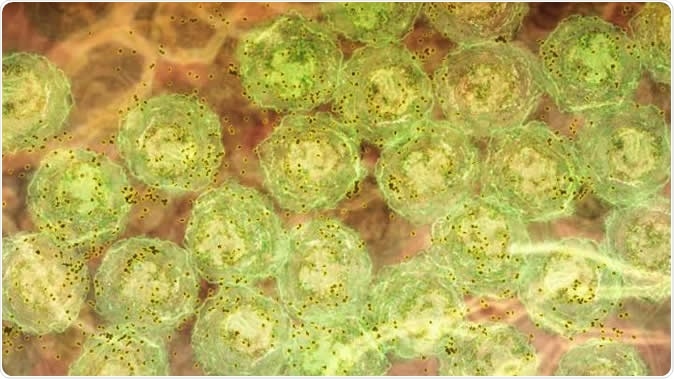

A discovery about how the immune system responds to malaria infection could lead to better treatments for hepatitis C, HIV and lupus. The research showed, in laboratory models, that strong inflammatory signals caused by malaria infection activate molecules that trigger B cells to produce highly potent antibodies to fight the disease. In this image, we see B cells (green) producing antibody (brown). The same inflammatory signals are seen in human malaria infections, chronic viral infections and autoimmunity. This suggests the discovery could be harnessed to develop new vaccines and therapies that are better able to fight infections such as hepatitis C and HIV, and treat diseases such as lupus. Image Credit: Walter and Eliza Hall Institute

The current study was led by researchers who have spent over ten years examining various aspects of the immune response to malaria. They cast some doubt on the long-held hypothesis that malarial infection is so successful because it manages to escape detection by the immune system, saying this is only one of its many adaptations to human parasitic existence.

Again, they point to the surprising lack of natural immunity following malarial infection. In most cases, protective immunity occurs after an infection with a bacterium or virus, lasting for life. However, says researcher Diana Hansen, “It is well known that an individual must continuously be exposed to malaria over many decades in order to develop protective immunity, during which time they are often sick, as well as spreading the disease.”

They focused their efforts on finding out what distinguished malaria from other infections which conferred lifelong immunity, and this gave birth to a collaboration between biologists, immunologists, and bioinformatic specialists.

The findings

Previous research by the same team showed that inflammatory molecules prevented the body from protecting itself by inhibiting a class of immune cells called helper T cells. These cells are critical to triggering antibody production by B cells, and if antibodies are not produced, long-term immunity cannot be developed.

In 2016, the scientists showed that in ordinary inflammation, the production of inflammatory signals triggered molecular inhibitors that prevented or stopped T helper cell development, and thus arrested antibody production.

In the current study, however, the opposite occurred. The presence of inflammation due to malarial infection caused B cells to undergo a kind of ‘training’ that resulted in the production of highly potent antibodies, transforming them into “professional predators”. This was a new phenomenon, which had previously never been recorded.

The question they faced was, if the immune system was really kickstarting the production of such powerful antibodies, why were people not becoming immune to malaria despite having multiple exposures over 20, 30 or 40 years?

The answer lies in the old quality vs quantity dilemma. In other words, inflammatory signals produced in response to malarial infection have a powerful effect on antibody quality, enhancing their specificity and potency. However, they also reduce the extent of B cell activation, ensuring that the impact of these “elite” cells is limited when it comes to preventing infection in the future.

What it means for other illnesses

The researchers grasped the potential of this discovery for disease conditions beyond malaria. Hansen says, “I think this discovery is so exciting because of the opportunity it offers in treating chronic viral infections and autoimmune disease.” The identification of the molecule that switches on the immune system to churn out very powerful antibody molecules, as well as of the inflammatory cytokines that modulate immune cell function, mean that scientists can now use this knowledge to change the way it functions.

They can use either this trigger molecule or other molecules downstream of it, to alter the way the pathway functions. This ability to precisely target a single component of a pathway could help them to treat many diseases in which it is active. For instance, in malaria or hepatitis C, or even in HIV, they can empower the immune system to produce antibodies that can clear the body of these infectious agents, curing the patient completely. On the other hand, in conditions like lupus, where the body produces antibodies against itself, being able to prevent the formation of destructive antibodies could help tremendously to limit or arrest tissue damage.

Hansen sums up: “The hope is that we would be able to create vaccines or therapies that would 'switch on' molecules that help to produce these elite B cells to fight chronic infections better, or ‘switch off’ the same molecules in autoimmune diseases to stop the production of B cells, such as lupus.”

Journal reference:

Transcription Factor T-bet in B Cells Modulates Germinal Center Polarization and Antibody Affinity Maturation in Response to Malaria Ly, Ann et al. Cell Reports, Volume 29, Issue 8, 2257 - 2269.e6, https://www.cell.com/cell-reports/fulltext/S2211-1247(19)31409-3