A new study shows that gut microbes can modulate the severity of norovirus infection (the stomach flu, or the winter vomiting bug), based on the gut location first affected. Published in the journal Nature Microbiology on November 25, 2019, the study indicates new possibilities to treat norovirus infection.

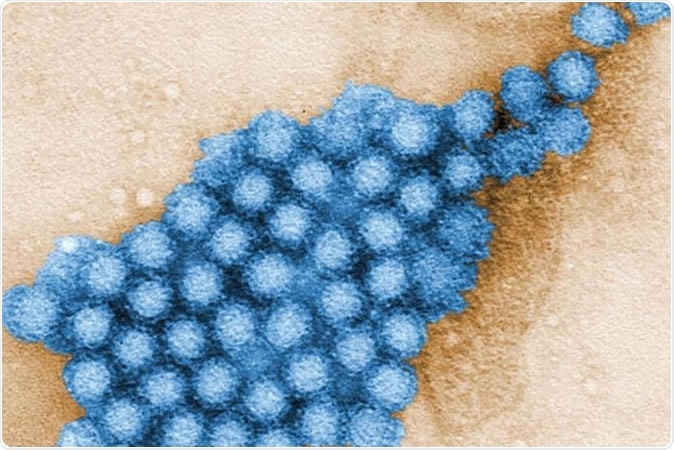

A new study led by Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis reveals details about how gut microbes interact with norovirus infection in the mouse gut. The research opens up new ways of thinking about potential therapies for this intestinal infection. Shown are Norovirus particles. CDC/ CHARLES D. HUMPHREY

Norovirus infections

Norovirus infections spread rapidly and cause intensive diarrhea and vomiting. They can create havoc in locations containing large numbers of people, including nursing homes, schools, cruise ships and day care centers. Every year, over 200 000 episodes of fatal norovirus infection occur worldwide, and most deaths are in the developing world. There is only symptomatic treatment for this infection.

Norovirus infections spread rapidly through food or water contaminated with the bacteria, typically from the faeces of anyone sick with the virus. The best way to prevent norovirus infections is by frequent handwashing, rinsing raw fruits and vegetables, staying away from public places when affected by the infection and another two days afterwards, and keeping away from food preparation for the same period.

Norovirus infection is especially dangerous in young children, older adults and individuals with compromised immune systems. The study was based on the interaction of gut microbes with norovirus to find new therapies that could help eliminate the infection.

The gut microbiome

The human gut contains at least 30 trillion microbes, comprising a thousand different bacterial species. These microbes interact with human health in many ways, including inhibiting the growth of pathogenic bacteria, shaping gut and body immunity, synthesizing a host of useful nutritional and biochemical factors, and keeping many body processes running smoothly and evenly. Even early brain development and maturation after birth has been linked to the presence of a normal gut microbiome.

The current study

The researchers used norovirus infections in mice to study the severity of viral infection in the presence of normal gut bacteria.

Interestingly, the infection became worse when the norovirus interacted with normal bacteria in the lower small intestine, a finding that replicates those of earlier mouse studies. An unsolved puzzle in these cases was the apparent failure of antibiotic resistance to affect norovirus virulence in mice, an unexpected finding in view of the above.

However, the current study shows that when it comes to the upper small intestine, the presence of commensal gut bacteria inhibits viral infection. Thus, depending on where the infection was, the bacteria had completely opposing effects.

In other words, the gut isn’t just a very long tube of homogeneous bacterial deposits that acts the same way throughout its length, but a dynamically varying structure that responds in drastically different ways to the same infection.

Bile acids and gut bacteria

As they explored the reasons for this difference in response, they found that bile acids played a key role in this process. Bile acids are steroid-like molecules that are produced by the liver and form the major part of the active components in bile. These compounds are better known to aid digestion of fats in the intestine. However, their production is also powerfully influenced by gut bacteria throughout the length of the intestine.

The study showed that bile acids triggered immune reactions in certain parts of the gut to ensure that it becomes combat-ready when faced with intestinal viruses. Their presence in the upper part of the small intestine enhanced immune response to the infection, but in the lower part, the bile acids stimulated the activation of interferon III, a molecule that forms a key component in the body’s defences to viral infection.

This finding could help explain why different people show such different reactions to norovirus infections. In fact, while some infections are completely asymptomatic, others cause severe illness. Some of the blame can now be laid at the door of interactions between bile acids and the gut microbes, which vary from person to person, as well as the location of the infection along the gut. Everyone has a gut microbial community containing different proportions of various organisms. The severity of each infection could thus be modulated by all these factors that determine how the gut immune system sees the virus and responds to it.

Implications

In turn, this could help formulate novel strategies to prevent or treat norovirus infection. For instance, scientists could try to stimulate interferon III activation along the whole gut lumen instead of only in the upper part of the small intestine, as at present.

There could be still more ways to modulate gut immunity using bile acids or the gut microbiota, to prevent norovirus from taking a hold on the gut.

Source:

Journal reference:

Grau, K.R., Zhu, S., Peterson, S.T. et al. The intestinal regionalization of acute norovirus infection is regulated by the microbiota via bile acid-mediated priming of type III interferon. Nat Microbiol (2019) doi:10.1038/s41564-019-0602-7, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41564-019-0602-7