Eat a heart-healthy diet and reduce your risk of heart disease and stroke. It On the other hand, there is no ‘safe’ or ‘unsafe’ limit of dietary cholesterol that can be recommended at present, for the simple reason that no study has yet defined this limit. It is therefore better to concentrate on optimizing dietary patterns for heart health.

Blood cholesterol

Cholesterol is an important molecule in the body, found in the membranes that cover every cell and many cell organelles. Much of this cholesterol in the blood is made by the liver for this very purpose. However, foods that are full of saturated fat, such as red meat, fatty processed meat, butter, cream and full-fat milk, are rich in cholesterol as well. Eating such foods can push up blood cholesterol levels as a result.

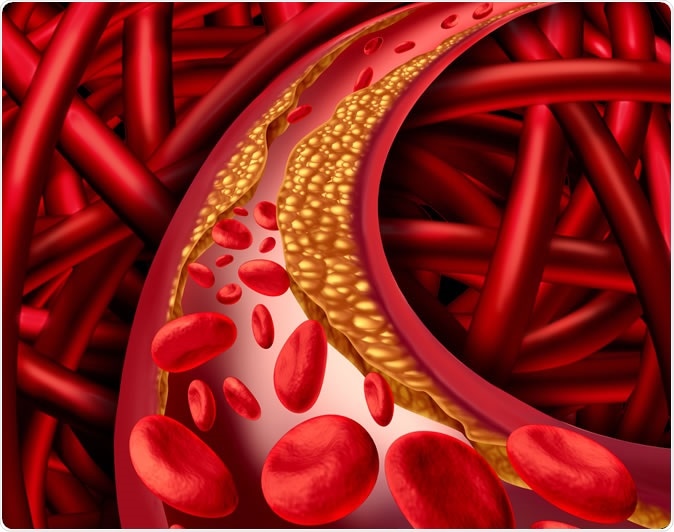

Artery problem with clogged arteries and atherosclerosis disease medical concept with a human cardiovascular system with blood cells with plaque buildup of cholesterol symbol of vascular illness. Image Credit: Lightspring / Shutterstock

When blood cholesterol levels are too high, the arteries develop a thick waxy coating, in a process called atherosclerosis. Not only does this reduce the natural elasticity of the arteries, but it makes them liable to become narrowed. The rough fatty surface of the cholesterol build-up also encourages clots to form, which can break off and travel as fragments through smaller and smaller vessels, until they lodge in a blood vessel too small for them. This causes the blockage of the blood supply to the organ supplied by that vessel, causing illnesses such as a heart attack (if the blocked vessel supplies heart muscle), or a stroke (if it is in the brain).

The controversy

On one hand, intensive and repeated research has not been able to prove that eating cholesterol-rich foods increases blood LDL levels, at the current level of consumption. The scientists behind the Advisory attribute this to the possible differences in dietary study design, and the amount of cholesterol fed to the subjects in the studies.

Observational studies in several countries have shown that dietary cholesterol is linked to a higher risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD). However, these cannot prove that one causes the other, only that they are generally seen together. If, for instance, we were to show that carrying umbrellas is generally associated with rainy weather, the assumption that the first caused the second would be invalid – in fact, the reverse would be true.

With respect to studies trying to prove a link between diet and cholesterol the difficulty is still higher because the participants generally fill out food questionnaires to supply data. And also, since most foods that contain relatively high levels of cholesterol are also high in saturated fat, making it a hard job to separate the effects of one from the other on blood cholesterol levels and on CVD risk.

The analysis

The Advisory also reports a meta-analysis of several randomized controlled studies of dietary interventions, that do have the ability to prove that one event causes another. The result of the analysis is that with a very high consumption of dietary cholesterol, exceeding normal intakes, the level of LDL in blood increases proportionally with dietary cholesterol levels - whatever the type of fat.

The limitations

The meta-analysis included only those studies where food was given to the participants, thus making sure that the food records were precise. On the other hand, since such trials are quite costly, they include only small numbers of participants and were low-powered as a result. This means that the number was too low to be able to make valid comparisons between the effect of LDL, HDL, and total cholesterol in driving up CVD risk. This is a serious limitation, because HDL is thought to be beneficial to heart disease risk, while total cholesterol could also change the overall effect.

The recommendation

The best way out, in view of the low level of evidence for the causal role played by different types of dietary cholesterol in CVD risk, say the experts, is to eat a heart-healthy diet.

AHA nutritionist Jo Ann Carson summarizes: “Consideration of the relationship between dietary cholesterol and CVD risk cannot ignore two aspects of diet. First, most foods contributing cholesterol to the U.S. diet are usually high in saturated fat, which is strongly linked to an increased risk of too much LDL cholesterol. Second, we know from an enormous body of scientific studies that heart-healthy dietary patterns, such as Mediterranean-style and DASH style diets (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) are inherently low in cholesterol.”

What would such a diet look like?

Most diets that are easy on the heart and blood vessels contain a greater proportion of fruit, vegetables, whole grains, low-fat dairy, lean meat cuts, and protein from either lean meat, fish, poultry or plant sources, with seeds and nuts. Fats from saturated fat sources like animal meats and full-fat dairy are excluded in favour of polyunsaturated sources like corn, soybean or canola oils, of plant origin. Foods that have significant added salt or sugar are also restricted.

Since eggs were not found to be related in any significant way with CVD risk in the small studies included in the meta-analysis, the Advisory says one egg a day is part of a heart-healthy diet for the normal person. Overall, therefore, there is no significant change from the Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease, issued in 2019 by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association – eat less cholesterol, keep your heart healthy. However, there is no specific limit marking a level of dietary cholesterol as healthy or unhealthy, says the Advisory.

Source:

Journal reference:

Dietary Cholesterol and Cardiovascular Risk: A Science Advisory From the American Heart Association Jo Ann S. Carson, PhD, RDN, FAHA, Chair, Alice H. Lichtenstein, DSc, FAHA, Vice Chair, Cheryl A.M. Anderson, PhD, MPH, MS, FAHA, Lawrence J. Appel, MD, MPH, FACP, FAHA, Penny M. Kris-Etherton, PhD, RD, FAHA, Katie A. Meyer, ScD, MPH, Kristina Petersen, PhD, APD, Tamar Polonsky, MD, MSCI, Linda Van Horn, PhD, RD, FAHA, https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000743