Artificial intelligence (AI) may be a useful and even essential tool in selecting the best treatment for depression, according to a new study published in the journal Nature Biotechnology on February 2020.

A new study finds that measuring electrical activity in the brain through electroencephalogram (EEG) can help predict a patient’s response to an antidepressant. The study is the first of several stemming from a national trial aimed at establishing biology-based, objective strategies to remedy mood disorders.

The finding comes from a national clinical trial based on the need to understand mood disorders. The most important conclusion reached by the researchers is that a computer can provide an accurate outcome prediction for antidepressant use by a given patient, based on the brain activity of that individual.

Several studies from the trial data analysis have already been published, and the core finding is that advanced technology can help to diagnose and treat depression with greater accuracy. The challenge is to bring these findings into clinical practice. Nonetheless, the scientists say that the use of AI, brain imaging and blood tests will change the face of psychiatry in the near future.

Antidepressant use is up 65% over the last 15 years, according to NHANES (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey). This widespread use of these drugs makes it a matter of high priority to understand how and which drugs will be effective in the management of depression.

Says researcher Madhukar Trivedi, “We provided abundant data to show we can move past the guessing game of choosing depression treatments and alter the mindset of how the disease should be diagnosed and treated.”

The study

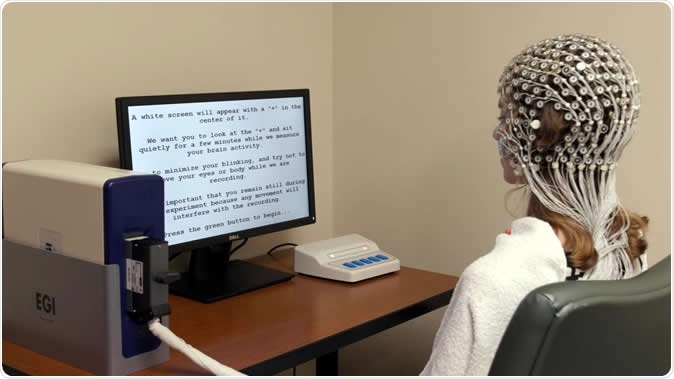

The research was carried out on over 300 individuals with clinical depression. The patients underwent baseline brain activity assessment using electroencephalography (EEG). They were randomly assigned either an SSRI (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor), which is the most commonly used kind antidepressant, or a placebo.

The researchers then designed a specialized machine-learning algorithm using the EEG data, to tell them which patient had the highest chances of improving if put on a given medication for 2 months.

The findings

The machine spat out figures about the outcomes of each of the assessed patients. Astonishingly, the predictions were on the spot. Not only so, when the scientists followed up the patients afterwards, they found that those whom the machine deemed least likely to benefit from the antidepressant could improve with counseling or brain stimulation.

To confirm these findings, three more groups of patients were formed to test them.

The machine used data from earlier studies to learn what patterns of brain activity were actually linked to the kind of brain activity impairment that improves with antidepressant therapy. This data came from the EMBARC trial for patients with major depression. The trial lasted 16 weeks at four different locations in the US. The aim was to put depression diagnosis and management on a firm foundation. The researchers used brain imaging, DNA testing, blood samples and other relevant tests to devise a biological rather than subjective method to treat these mood disorders.

The motivation was provided by a still earlier study, called STAR*D, in which the scientists found that up to a third of patients failed to achieve clinical improvement to an adequate level with the first antidepressant they tried. Therefore, says Trivedi, “We went into this thinking, 'Wouldn't it be better to identify at the beginning of treatment which treatments would be best for which patients?”

With EMBARC, older research has assessed the role of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain at rest as well as during emotional processing, along with other tests, in predicting the patient’s role. This data is continuing to be processed after these elementary findings.

Implications and the future

Another researcher, Amit Elkin, says, “This study takes previous research, showing that we can predict who benefits from an antidepressant, and actually brings it to the point of practical utility.” Trivedi says they will probably use the EEG in the majority of patients because it is not only much cheaper but just as or better at risk prediction than other more expensive tests.

However, some patients will need to go on to get an MRI scan or a blood test, simply because of the changing expression of depression – the “many signatures of depression”. Explains Trivedi, “Having all these tests available will improve the chances of choosing the right treatment the first time.”

The next step is to design an AI interface that is compatible with the broad range of EEG machines used across the USA, and to get approval for the use of the device from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Meanwhile, other large studies are going on to boost the rate of response with antidepressants.

One is the D2K study that aims at 2,500 depressed or bipolar individuals, with a follow-up of 20 years. the RAD, on the other hand, has a similar strength of 2,500 people aged 10-24 years. This is designed to pick up risk factors for mood or anxiety disorders. Some of these participants will be used to assess both the EEG and various other test combinations. The aim is to find the best treatment, by eliciting the best fit (biological signature), as Trivedi says, “Our research is showing that they no longer have to endure the painful process of trial and error.”

Journal reference:

Wu, W., Zhang, Y., Jiang, J. et al. An electroencephalographic signature predicts antidepressant response in major depression. Nat Biotechnol (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-019-0397-3