A team of researchers from the University of Texas at Austin and the National Institutes of Health have managed to make significant progress in the development of a vaccine against the fast-spreading and virulent COVID-19/Novel coronavirus that started in Wuhan, Hubei province of China in December 2019 and is still infecting thousands. Their study outlining the findings was published today in the latest issue of the journal Science.

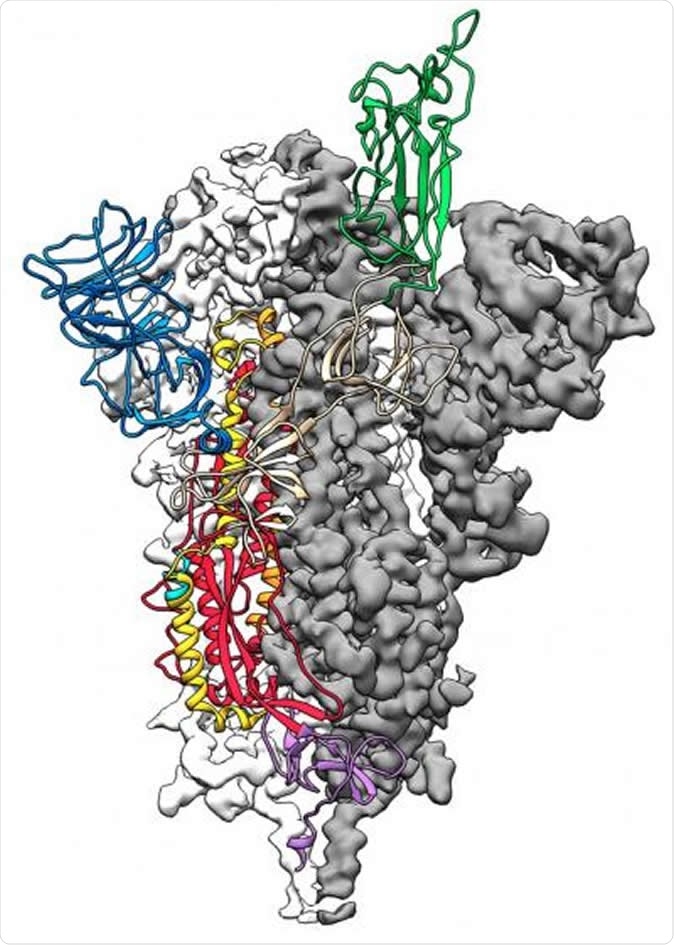

The team of researchers managed to create a 3-dimensional atomic-scale map of the part of the virus that could be used to develop the vaccine. This part of the virus is the vital part that attached to the human cells and thus infections, them, explained the researchers. The part called the spike protein remains an essential identifying region of the virus that could help the researchers develop antiviral drugs as well as vaccines against the deadly virus.

According to lead researcher Jason McLellan associate professor at UT Austin, the team has been studying coronaviruses for several years now and has been exploring other viruses of the same family, including SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV. On these coronavirus strains, the team had also successfully developed a method so that the spike proteins on their surfaces could be locked into a shape that would make them easily visible and analyzable. This locking of the proteins would also allow them to turn them into vaccines, McLellan explained.

Jason S. McLellan, associate professor of molecular biosciences, left, and graduate student Daniel Wrapp, right, work in the McLellan Lab at The University of Texas at Austin Monday Feb. 17, 2020. Credit: Vivian Abagiu/Univ. of Texas at Austin.

With this background knowledge and technology, the team was capable of working rapidly with the new strain of the virus or the COVID-19, he explained. McLellan said, "As soon as we knew this was a coronavirus, we felt we had to jump at it...because we could be one of the first ones to get this structure. We knew exactly what mutations to put into this because we've already shown these mutations work for a bunch of other coronaviruses." The study's first authors Ph.D. student Daniel Wrapp and research associate Nianshuang Wang worked alongside McLellan in understanding the cracking of the code of this new strain of the virus.

The UT Austin website says, "We seek to obtain structural information on [these] proteins and their interactions with host macromolecules and translate this knowledge into the rational development of therapeutic interventions such as small-molecule inhibitors, protective antibodies and stabilized vaccine immunogens."

For this new study, the team received a detailed genetic map of the new strain of the virus from the Chinese researchers. From these sequences, they could create samples of the spike protein that were stabilized for further experimentation. To create the spike proteins and then map it, the team took 12 days. At the end of the time, they had a three-dimensional atomic map of the spike proteins on the viruses. These molecular structures of the spike proteins also told them the possible structure that bound to the human cells to infect them. Once the structure was deciphered, the team sent their findings to the journal for rapid publication considering the importance of such research at this time of an impending pandemic.

In order to create a 3D atomic map of the proteins on the viral surface, the team used a complex technology involving cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) in UT Austin's new Sauer Laboratory for Structural Biology. This technology has been used before to create 3D atomic maps of molecules, cellular parts, and viruses. McLellan explained, "We ended up being the first ones in part due to the infrastructure at the Sauer Lab. It highlights the importance of funding basic research facilities."

This is a 3D atomic scale map, or molecular structure, of the 2019-nCoV spike protein. The protein takes on two different shapes, called conformations--one before it infects a host cell, and another during infection. This structure represents the protein before it infects a cell, called the prefusion conformation. Image Credit: Jason McLellan/Univ. of Texas at Austin

The team explained that the part of the spike protein they mapped was only a small part of it that was sticking out of the virus and usually binds to the human cell, it infects. They said that this tiny part of the spike protein was enough to bring out an immune response in a host body. An immune response is what a vaccine elicits to provide the body with immune protection against the virus attack. Thus this part of the spike protein could help researchers develop a vaccine against the virus, the authors of the study explained.

Barney Graham, deputy director of the NIH's Vaccine Research Center (VRC) in Bethesda, was part of the experiments that explored the three-dimensional image of the spike proteins on the virus.

McLellan and his colleagues have designed further studies to see the antibodies that the host immune system brings out in response to part of the spike protein that they created. These antibodies, if created in the lab, could help fight the attack of the virus when injected into an infected person, they expect. This could be a great help to first-line healthcare personnel and infected individuals, they explained.

This study was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Journal reference:

Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation By Daniel Wrapp, Nianshuang Wang, Kizzmekia S. Corbett, Jory A. Goldsmith, Ching-lin Hsieh, Olubukola Abiona, Barney S. Graham, Jason S. Mclellan Published Online19 Feb 2020 Doi: 10.1126/science.abb2507, https://science.sciencemag.org/content/early/2020/02/19/science.abb2507