Immune cells detect and eliminate abnormal cells and particles. Cancers are characterized by a resistance to immune attack mediated by a variety of tactics. This includes genetic changes that make them invisible to the immune system's patrolling cells, expressing proteins on the cell surface which switch off immune targeting, and regulate the normal cells around the tumor so that they shield the tumor from immune activity.

Immunotherapy is designed to get around these barriers. For instance, immune checkpoint inhibitors stimulate the immune system by blocking the immune checkpoints that regulate immune responses and prevent hyperactivation of the immune system.

Another approach is T-cell transfer therapy or adoptive immunotherapy and adoptive cell therapy. This strategy enhances the ability of the T cells to attack and kill cancer cells. These cells are immune cells selected for their high level of activity against cancer, sometimes altered, grown in culture and infused back into the body intravenously.

Other strategies include monoclonal antibodies, designed to attach to specific targets on cancer cells, so as to mark them for destruction by immune cells; therapeutic vaccines to strengthen the immune response against cancer cells and destroy them, which are different from the preventive vaccines; and immunomodulators which again make the immune system more active against cancer.

Immunotherapies aren't effective or even approved against all types of cancer. They may also cause side effects, especially the type called CAR-T therapy, which can sometimes be quite serious.

The current study was on the use of molecules that reactivate the gene called gasdermin E.

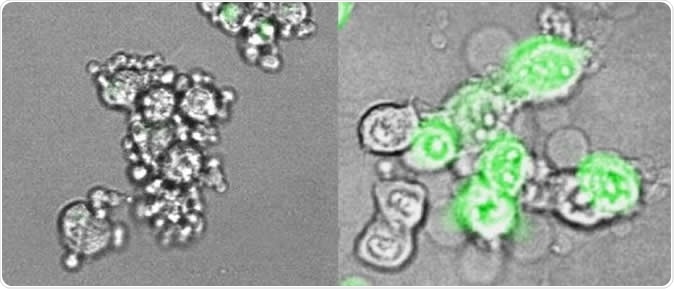

At left, cancer cells from an immunologically 'cold' tumor, in which gasdermin E has been suppressed, undergo a slow, uneventful death. Their outer membrane remains intact and they quietly shrink. The cancer cells at right have had gasdermin E re-introduced: they blow up, forming giant membrane balloons, and release molecules that trigger inflammation and protective immune response. Image Credit: Zhibin Zhang/Lieberman Lab, Boston Children's Hospital

Gasdermin E

Gasdermin E is part of the immune response native to humans, but which is typically inhibited in multiple cancer types. Describing it, researcher Judy Lieberman says, "Gasdermin E is a very potent tumor suppressor gene, but in most tumor tissues, it's either not expressed or it's mutated."

As a result, the reactivation of this silent gene within tumor cells is capable of shifting the tumor from a state in which it is 'under the radar' immunologically to one which is easily detected and attacked by the immune system. This is called switching from an immunologically cold tumor to one which is hot, or easily detectable and one which can be attacked by the immune system.

The study findings

The researchers conducted a study using cell lines derived from mouse tumors, to find out more about how gasdermin E operates. The study was based on the process of apoptosis, an orderly sequence of actions in which the cell quietly dies without damaging nearby cells or the body as a whole. This holds good for most cancer cells as well. However, if gasdermin E is active, the dying cell bypasses the apoptotic pathway, to die in a blaze of ruptured membranes, leaking intracellular components, and intense inflammation. This highly 'public' death process is called pyroptosis.

The good thing about pyroptosis is that it sounds a clanging alarm throughout the body that alerts killer T cells to the fact that a highly toxic invader is on the loose and needs to be suppressed immediately. This immune response is what will attract these commando cells to the site of cell death, where they go into action to kill the remaining tumor cells as well based on their immunological unlikeness to normal cells.

The current study focused on demonstrating this response to gasdermin E reactivation. The researchers are now trying to identify therapeutic drugs that can turn on this gene and thus rally immune killer cells to the tumor site.

The implications

If inflammation occurs around a tumor, it attracts many kinds of anti-tumor immune cells, which make the tumor recognizable to the immune system as a threat and not a friend. This may spark an adequate immune response, which could result in the activation of the host's own responses against the tumor cells. The difference between the currently proposed strategy and other previously used approaches is the use of a common inflammatory pathway, which leads to a much broader spectrum of anti-tumor immune activity. This may be compared to attack along a whole front rather than just one line of attack.

Lieberman says, "What we're suggesting is that if we can turn on the danger signal, which is inflammation, we can activate lymphocytes more fully than with other immunotherapy approaches, and have immunity that is potentially much broader. Combining activation of inflammation in the tumor with approved checkpoint inhibitor drugs could work better than either strategy on its own."

Journal reference:

Zhang, Z., Zhang, Y., Xia, S. et al. Gasdermin E suppresses tumour growth by activating anti-tumour immunity. Nature (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2071-9