The current COVID-19 pandemic is caused by a novel coronavirus called SARS-CoV-2, or severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an infectious disease caused by SARS-CoV-2. Coronaviruses are a large family of RNA viruses with genomes containing up to 32 kilobases. They cause disease in humans as well as animals. Camels, bats, and cats can all become infected by coronaviruses, which cause gastrointestinal or respiratory illnesses. In some cases, these animal viruses can jump to humans – observed first in the middle of the last century.

Coronaviruses are associated with a broad risk spectrum, from the 30% mortality with the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) to zero mortality for common colds. Many of these viruses can cause heavy colds, with fever, sore throat, pneumonia, bronchitis.

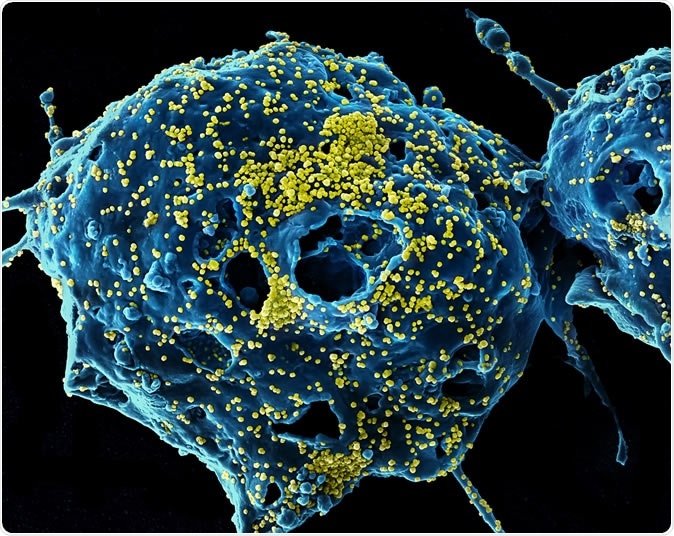

MERS Virus Particles Colorized scanning electron micrograph of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome virus particles (yellow) attached to the surface of an infected VERO E6 cell (blue). Image captured and color-enhanced at the NIAID Integrated Research Facility in Fort Detrick, Maryland. Credit: NIAID

In 2002, a circulating coronavirus strain caused severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in Guangdong province, China, and was therefore named the SARS virus. This outbreak caused several thousand deaths. In 2003, the same virus emerged again in Hong Kong.

Ten years later, a similar coronavirus causing, again, acute respiratory symptoms, emerged in the Middle East, called the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome virus (MERS-CoV).

Overall, there are four types of coronaviruses, alpha, beta, gamma, and delta. The first two are associated with human illness. The SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and the current SARS-CoV-2 are all from the beta genus.

How do coronaviruses damage the lung?

The SARS-CoV and the MERS-CoV infected the ciliated and nonciliated cells of the airway epithelium, respectively, as well as the type II pneumocytes. They made the jump from market civets and dromedaries to human hosts, respectively. Both are thought to have originated in bats through genetic recombination because the direct precursor of the SARS-CoV has never been found in any bat over 15 years of exploration. These viruses have been studied in detail to understand how coronaviruses attack cells, replicate, and cause clinical illness.

The SARS-CoV binds the ACE2 receptor on the ciliated bronchial epithelium. The S protein forms a triple-headed molecule, with a receptor-binding domain on the tip of each head. Different strains of the virus from different hosts have varying binding affinities for the human ACE2 enzyme, which affects their ability to infect human cells. The strain responsible for the 2002 epidemic had high affinity and high infectivity for human cells containing ACE2. This led to its efficient spread. Low or moderate affinity causes loss of epidemic transmission. The high infectivity is in part because of the efficient recognition of the human ACE2 receptor. This is because of specific mutations that enable efficient receptor binding.

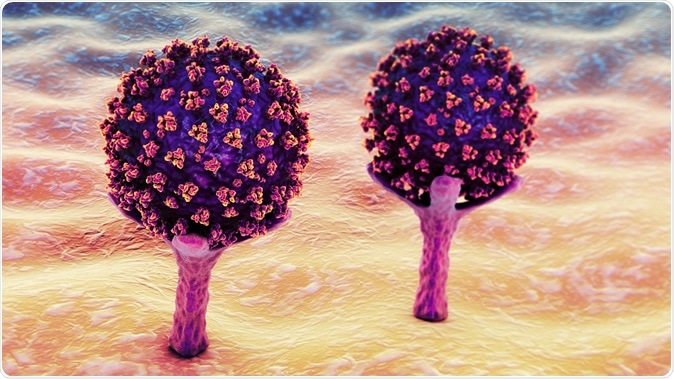

SARS-CoV-2 viruses are binding to ACE-2 receptors on a human cell, the initial stage of COVID-19 infection. Conceptual 3D illustration credit: Kateryna Kon / Shutterstock

The interactions between the virus and the host cell trigger a flood of inflammatory cytokines, cell signaling molecules, which lead to the recruitment of specific T cells to destroy the infected cells. This is intended to stop the viral spread. However, the inflammation also causes nonspecific changes such as edema and inflammatory cell infiltration, along with marked shedding of the alveolar epithelial cells. The septa between the alveoli are widened, swollen and damaged, and infiltrated by inflammatory cells.

Thus, SARS‐CoV infection can cause the lung tissue to break down, become filled with inflammatory cells, thicken, and lose function. The walls of the arterioles in the pulmonary interstitium undergo damage, which again emphasizes the role played by intense inflammation in the course of COVID-19.

The lifecycle of the coronavirus

The virus has a spike (S) glycoprotein, which binds to the receptor on the host cell. This causes activation of the S protein by the cleavage of the host cell protease. The outcome is the entry of the virus into the host cell either by endocytosis or by the fusion of the cell membrane with the viral envelope.

The genome now appears within the host cell cytoplasm and attaches to the ribosome of the host cell where translation can begin. This gives rise first to a long polypeptide precursor, which is split into multiple non-structural proteins that together form a replicase-transcriptase complex (RTC). This allows the virus to replicate and transcribe its genome. This, in turn, leads to viral release from the cell to infect new cells.

Transmission

Most of the viral spread occurs among close contacts through droplets generated during a cough or a sneeze. Touching, shaking hands, touching surfaces contaminated with the virus and carrying the same hand to eyes, mouth or nose, and rarely, fecal-oral contamination are all possibilities.

Coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19)

Following the reported outbreak of a cluster of pneumonia cases in the city of Wuhan, China, at the end of 2019, the causative agent was found to be a novel coronavirus. This is the one now called SARS-CoV-2, and its genome is about 70% similar to the SARS-CoV-2.

There is no vaccine or specific treatment. Severe infections will require hospitalization and, often, intensive care unit (ICU) admission for mechanical ventilation. To prevent infection, the following steps are strongly recommended:

- Inform health authorities if coming home after foreign travel and if there are any symptoms such as fever, dry cough or headache, a slight cold, shortness of breath,

- Frequent, thorough handwashing with soap and water

- Keep hands away from nose, mouth, and eyes

- Properly covering the mouth and nose during a cough or sneeze

- Properly cleaning and disinfecting surfaces and objects

- Stay home when possible to keep out of infective zones, especially when there are sick people around you or if you are sick.

- Observe social distancing (no contact within 1 meter) whenever you have to go out

- Self-isolation for anyone who feels unwell with fever, dry cough, body aches, slight runny nose, etc.

Testing for the virus is typically available only for severely ill patients. About 80% of infected patients become better without special care, having experienced only mild to moderate illness. One in six will be critically ill, however, and at present, about 3% of victims are found to die, mostly of ARDS.