Zoonotic spillover events like the current novel coronavirus pandemic present threats to human health. But what is zoonotic spillover and how do they occur?

Since they were first described, these pathogens have caused many outbreaks, epidemics, and pandemics, with many being deadly. A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism; its only purpose for existing is to make more viruses.

Most human infectious diseases are initially transmitted from animals, including the Ebola virus, the H1N1 influenza virus, the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the SARS coronavirus (SARS), MERS virus, and now, the potent novel coronavirus, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).

This process is called zoonosis, a term that refers to infectious diseases that are transmissible to humans from other animal species. Zoonotic diseases are a group of infectious diseases naturally transmitted between animals and humans. The most significant risk for zoonotic disease transmission occurs at the human-animal interface through direct or indirect human exposure to animals, their products (e.g., meat, milk, eggs.) and/or their environments.

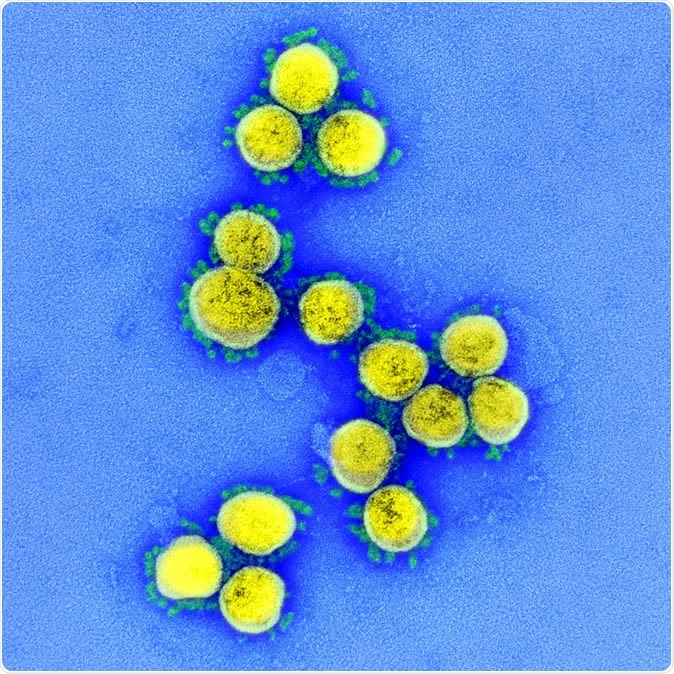

Novel Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 Transmission electron micrograph of SARS-CoV-2 virus particles, isolated from a patient. Image captured and color-enhanced at the NIAID Integrated Research Facility (IRF) in Fort Detrick, Maryland. Credit: NIAID

Human interaction with animals is a significant risk factor for a multitude of high impact zoonoses, including many bat-origin viral diseases. Therefore, analyzing mammalian viruses sheds light on cross-species spillover, with potential benefits for public health.

Zoonotic spillover

Zoonotic spillover, defined as the transmission of a pathogen from an animal to a human, is a poorly understood phenomenon that presents a global public health threat. Spillover is a common event; in fact, more than two-thirds of human viruses are zoonotic.

Zoonotic pathogens have to surpass a series of barriers to jumps to humans, so to better understand how a spillover happens, there needs to be a greater understanding of these barriers to predict or prevent epidemics in the future.

The most recent spillover event, the COVID-19 pandemic, has sparked the initiation of studies and experiments on how to stem the infection, and possibly, to develop new vaccines or therapeutics to treat patients hit by the life-threatening virus.

The COVID-19 disease is known to be caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which has jumped from bats to an intermediate host animal, before making residence in humans. Many experts believe the virus leaped to a pangolin, which is part of the wildlife trade in the Huanan seafood market in Wuhan City, Hubei Province, China. The first known case was reported in the area, followed by other patients who also visited the wet market.

A traditional market in Asia where bats are sold as food alongside other animals as dogs or snakes. Image Credit: Maurizio Biso / Shutterstock

When viruses jump to humans

Usually, a virus starts in a reservoir. The virus replicates in a primary host, like bats. Then, when another species, such as wild animals come in contact with the reservoir, they may contract the virus, which is termed as exposure.

In the stage called breakthrough, the virus overcomes the immune response of the new host, and transmission happens. The virus can now spread from one host to another, like humans. The tipping point happens when new hosts become infected at an increasing rate.

Coronaviruses, which have caused previous epidemics, are known to cause spillover events since they seem to have already overcome many of the many natural obstacles that usually limit a virus to a single species. For instance, in the 2000s, the SARS outbreak was thought to start from bats, and then the virus leaped to Himalayan palm civets, while the MERS-CoV was considered to jump to camels. Scientists believe that the current pandemic started due to the wildlife trade in China, and in the Huanan seafood market in Wuhan City, the virus was thought to linger in pangolins.

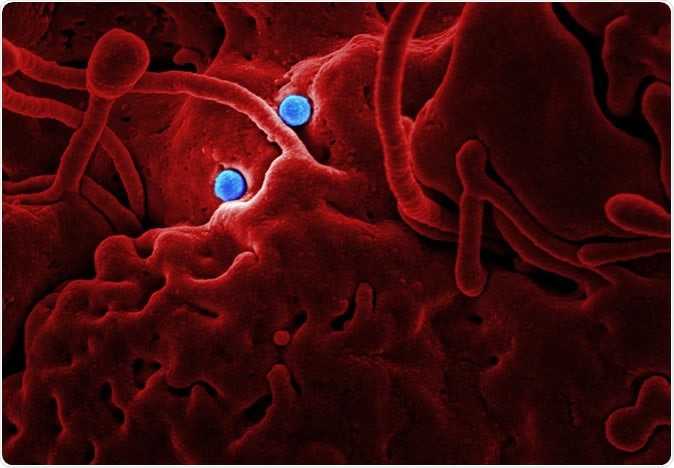

MERS Coronavirus Particles - MERS-CoV particles on camel epithelial cells. Credit: NIAID in collaboration with Colorado State University

Further, coronaviruses are also 'reverse zoonotic', which means that it can be transmitted between animals and people then back again; hence, the virus can also jump from humans to animals. For instance, the SARS-CoV-2 was detected in two dogs in Hong Kong, and now a tiger in a New York zoo.

How do viruses jump from animals to humans? - Ben Longdon

Experts believe that many factors can lead to a spillover, including urbanization, the population of the animal and humans, demand for animal protein, type of virus, connectivity between people, travel, climate change, habitat loss, and increased interactions between humans and animals. In most cases, developing countries are at a higher risk of animal spillover due to decreasing animal habitats, a lack of adequate medical care, and poor sanitization. Globally, zoonotic spillover has increased in the last 50 years, mainly due to the environmental impact of agriculture, deforestation, changing wildlife habitats, and the effects of increased land use.

Many viruses exist on the planet, while relatively few threaten people, animals, and plants. Nevertheless, some viruses thrive in animals that can cause severe diseases in humans, such as the Ebola virus, H1N1 influenza virus, Marburg viruses, rabies-like lyssavirus, paramyxoviruses, and the Hendra and Nipah viruses.

Humans should have less contact with wildlife, to prevent the occurrences of disease outbreaks, since most of these viruses thrive in wildlife. Since the 1918 Spanish flu that ravaged the world, the COVID-19 pandemic is one of the worst outbreaks the world has seen, affecting most countries.

There are more than 1.34 million infected people, with more than 74,000 succumbing to the disease.