After tracing coronavirus signatures in different species, a new research article published in the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution suggests that stray dogs (more specifically dog intestines) may have acted as the origin of current severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic.

SARS-CoV-2 has infected two million people to date, resulting in coronavirus disease (COVID-19) accompanied by worrying mortality rates worldwide. Although there is a consensus that the novel coronavirus has crossed over from animals to humans, exact species of origin is still elusive.

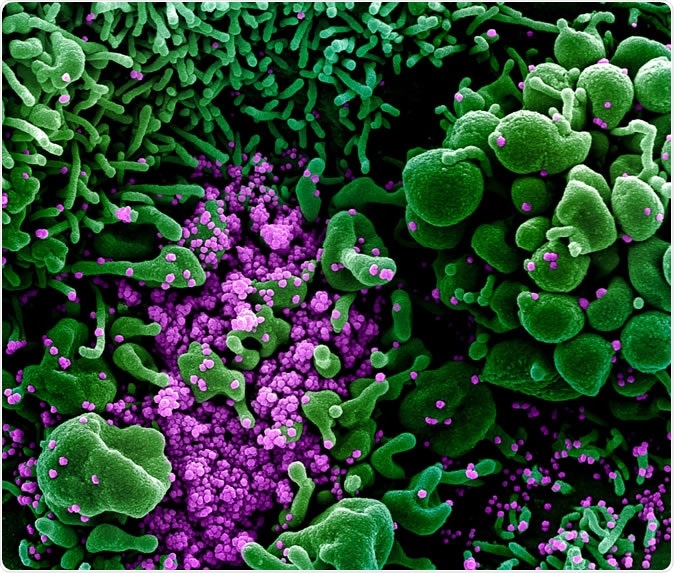

Novel Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 Colorized scanning electron micrograph of an apoptotic cell (green) heavily infected with SARS-COV-2 virus particles (purple), isolated from a patient sample. Image captured and color-enhanced at the NIAID Integrated Research Facility (IRF) in Fort Detrick, Maryland. Credit: NIAID

Accordingly, since the start of this pandemic, scientists have been striving to find an intermediate animal host between bats (which are known coronavirus reservoirs) and the inaugural event of SARS-CoV-2 introduction to humans. Snakes and pangolins were considered as likely intermediates, but the isolated viruses were too divergent from current SARS-CoV-2 – suggesting a common ancestor further back in time.

The role of stray dogs

The research article published in Oxford University Press journal Molecular Biology and Evolution delineates a new hypothesis of SARS-CoV-2 source and initial transmission – and implicates stray dogs in this event.

"The ancestor of SARS-CoV-2 and its nearest relative, a bat coronavirus, infected the intestine of canids, most likely resulting in the rapid evolution of the virus in canids and its jump into humans", explains study's corresponding author Dr. Xuhua Xia, a biology professor from the Department of Biology of the University of Ottawa and Ottawa Institute of Systems Biology in Canada.

"This suggests the importance of monitoring SARS-like coronaviruses in feral dogs in the fight against SARS-CoV-2", adds Dr. Xia, who is known for studying viral molecular signatures in different hosts for a long time now.

China, Hainan Island, Dadonghai Bay - Chinese vet rescues a stray dog. Image Credit: Evgenii Mitrokhin / Shutterstock

A genomic game of cat and mouse

When a virus invades a host, changes, and adaptations arise in their genomic information, just like a battle scar resulting from a fight with the immune system. All mammals have a crucial antiviral sentinel protein known as ZAP; this protein can prevent viral multiplication, degrade its genome, and stop further progression of the infection.

Within its genome, the virus contains a specific sequence of building blocks known as CpG dinucleotides (a cytosine followed by a guanosine), which basically acts as a noticeboard used by our immune system to seek and destroy the invader. This sequence is recognized by ZAP protein that patrols the lungs after being primed in the bone marrow and lymph nodes.

But viruses can ingeniously hit back. Single-stranded coronaviruses (like SARS-CoV-2) can steer clear of ZAP by reducing the number of their CpG dinucleotides, rendering in turn ZAP powerless. Consequently, this evolutionary trait of CpG loss is a survival response to human antiviral defenses.

"Think of a decreased amount of CpG in a viral pathogen as an increased threat to public health, while an increased amount of CpG decreases the threat of such viral pathogens," explains Dr. Xia. "A virus with an increased amount of CpG would be better targeted by the host immune system, and result in reduced virulence, which would be akin to natural vaccines."

The quest for CpG relatives

After examining a large number of coronavirus genomes, Dr. Xia found that pandemic SARS-CoV-2 and its most closely related bat coronavirus (BatCoV RaTG13) exhibit the lowest quantity of CpG among all close coronavirus relatives.

"This bat CoV genome is the closest phylogenetic relative of SARS-CoV-2, sharing 96% sequence similarity", says Dr. Xia.

When the study authors appraised the data in dogs, they observed that only genomes derived from canine coronaviruses (CcoVs) – which were the cause of a highly contagious intestinal disease in dogs around the world – exhibit CpG values similar to those found in SARS-CoV-2 and BatCoV RaTG13.

Furthermore, coronaviruses that infect the digestive system in dogs also contain lower amounts of CpG than those known to infect their respiratory tract. This points to the fact that SARS-CoV-2 may have stemmed after its ancestor evolved in dog's digestive system – a fact further reinforced by a recent report showing a significant burden of gastrointestinal symptoms in COVID-19 patients.

How the virus ended up in humans?

Canid behavior includes licking anal and genital regions, which is not only found during mating but in other circumstances as well. This may indeed facilitate viral transmission from the gastrointestinal system to the respiratory tract, as well as subsequent switch from gastrointestinal to a respiratory pathogen.

Based on the study results, the authors present a scenario where the coronavirus initially spread from bats to stray dogs consuming bat meat. Afterward, presumed strong selection against CpG in the viral genome while infecting dogs' intestines gave rise to rapid viral evolution towards reduced genomic CpG. Ultimately, such reduced CpG trait allowed the virus to evade human immune response mediated by ZAP and, thus, to become a severe human pathogen that we are faced with today.

"While the specific origins of SARS-CoV-2 are of vital interest in the current world health crisis, this study more broadly suggests that important evidence of viral evolution can be revealed by consideration of the interaction of host defenses with viral genomes, including selective pressure exerted by host tissues on viral genome composition", concludes Dr. Xia.

Journal reference:

Xuhua Xia, Extreme genomic CpG deficiency in SARS-CoV-2 and evasion of host antiviral defense, Molecular Biology and Evolution, msaa094, https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msaa094