The novel coronavirus has rapidly infected millions over the world in over 187 countries and territories, causing hundreds of thousands of deaths. One of the often-neglected and under-reported symptoms of the virus is the loss of the sense of smell or anosmia. Now, a new study out of Germany published on the preprint server medRxiv in April 2020 provides a quantified estimate of the magnitude of anosmia as a symptom of the coronavirus.

The sense of smell, as one of the five basic senses of the body, is often affected by diseases: in many illnesses that involve fever, anosmia, along with a lack of appetite, is not an uncommon symptom. The medical community classifies the sense of smell on three levels:

- Normosmia - normal sense of smell

- Hyposmia - some loss of accuracy in the patient’s sense of smell

- Anosmia - the patient’s sense of smell is effectively nonexistent

Coronaviruses, including severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), have been known to demonstrate a neuroinvasive propensity. A theory is currently being discussed, which features the olfactory neurons as a possible point of entry for the virus, which could then spread from the central nervous system to the periphery via transneural routes.

In support of this theory, a significant proportion of patients admitted with COVID-19 report a loss of taste or smell without any sign of nasal blockage or a runny nose.

The current study sought to establish the magnitude of anosmia associated with this virus objectively.

How was the study done?

The study was carried out as a prospective cross-sectional study, screening for anosmia among 45 confirmed and hospitalized positives for the virus, using reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing. They used 45 healthy people, both patients and healthcare workers as controls. All participants were over 18 and had no known smelling disorder. The median age was 56 for the patients and 54 for the controls.

The researchers looked at the clinical features of the disease and the outcome in anosmic and non-anosmic patients, in terms of the worst outcomes and on day 15 of the hospital course. They used an ordinal scale with six categories, namely:

- discharged

- hospitalized, not requiring supplemental oxygen

- hospitalized, requiring supplemental oxygen

- hospitalized, on (NIV) or high flow oxygen devices

- hospitalized, on invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO)

- death

The team used an olfactory test by Burghart called Sniffin’ Sticks. The test consists of twelve sticks bearing twelve recognizable odors. According to the manufacturers, individuals with normosmia can correctly identify 11-12 of them, on average. Patients with hyposmia can only identify 7-10, and those with anosmia can only identify less than 6.

They assumed a baseline prevalence of less than 5% anosmia in the control group.

The controls correctly identified a median of eleven of the twelve sticks; none showed anosmia. 73% of the control individuals were normosmic, and the remaining 27% were hyposmic.

On the other hand, 40% of coronavirus patients were diagnosed with anosmia. On average, coronavirus patients identify four sticks less than healthy individuals. The Sticks were more sensitive at detecting anosmia than self-reporting or taking medical history: 44% of anosmic patients and 50% of hyposmic patients were not aware of any abnormality in their sense of smell.

There was no correlation between clinical course, laboratory results, outcomes, and the presence of anosmia or hyposmia.

What do the results imply?

The study concluded that hyposmia and anosmia are common symptoms in coronavirus patients - more than 80% of the test sample showed either hyposmia or anosmia. However, only 49% of the patients actually reported having smelling disorders. This led the team to conclude that hyposmia and anosmia are commonly under-reported.

However, the team warns that the 12-stick test may be inaccurate in distinguishing between hyposmia and normosmia, and advises caution in interpreting the results in this class.

Olfactory neurons have been discussed as a possible point of entry for coronaviruses. They may be transferred to the central nervous system through a route of synapses.

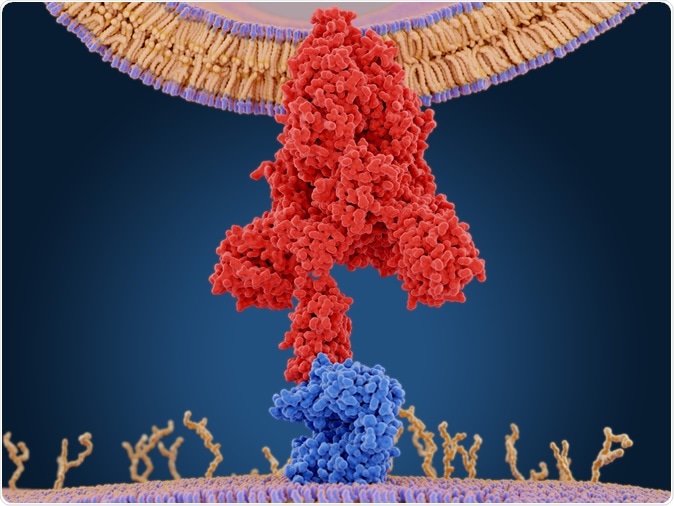

The molecules transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2) and Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 (ACE2) is essential for SARS-CoV-2 entry into human cells. Since olfactory sensory neurons do not co-express these proteins, it is unclear whether they directly participate in smelling loss due to the coronavirus.

The coronavirus spike protein (red) mediates the virus entry into host cells. It binds to the angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (blue) and fuses viral and host membranes. PDB entry 6cs2. 3d rendering. Image Credit: Juan Gaertner / Shutterstock

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Supporting data

In a mouse model which was infected by another human coronavirus (HCoV-OC43), the viral antigen was detected in the olfactory bulb after three days, and in the whole brain tissue after seven days. The study suggests that this data, combined with the wide distribution of ACE2 in the brain, the observation that HCoV is capable of causing neuronal damage to the cardiorespiratory centers in animal models, the increasing evidence that SARS-CoV-2 can cause neurological complications, the clinical picture with deterioration at about 1 week following illness, and the occurrence of acute respiratory failure, may be related to the neuroinvasive potential of SARS-CoV-2.

The study concluded that all coronavirus patients should be interviewed, and tested if possible, for olfactory disorders. All healthcare providers should be aware that this symptom could signal the presence of COVID-19. Finally, anosmia is not linked to more severe illness.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Source:

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Homuss, D., et al. (2020). Anosmia in COVID-19 patients. medRxiv preprint doi: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.28.20083311v1

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

Hornuss, D., B. Lange, N. Schröter, S. Rieg, W.V. Kern, and D. Wagner. 2020. “Anosmia in COVID-19 Patients.” Clinical Microbiology and Infection, May. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2020.05.017, https://www.clinicalmicrobiologyandinfection.com/article/S1198-743X(20)30294-9/fulltext