SARS-CoV-2 has spread rapidly and destructively through the whole world. As of now, there are almost 4.5 million cases and 300,000 deaths caused by this illness. The virus is highly infectious, spreading rapidly from person to person, especially within healthcare and family settings.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Control of viral spread depends mostly on knowing the different routes of transmission. The primary route is droplet transmission from the respiratory tract, but the virus may also spread via contact with infected surfaces and objects.

When a respiratory droplet is too heavy to remain suspended in the air near the place of origin, it settles on any surrounding surface. The next person to touch it is vulnerable to infection by contact between the part which touched the surface and the eyes, nose, or mouth.

The detection of a viable virus in feces as well as in other specimens from the gut has also raised the question as to whether the illness can spread via the fecal-oral route. The current study aims to answer these questions.

Testing for Viral Stability on Surfaces, Feces, and Urine

The researchers tested the stability of the virus on nine objects made of a variety of materials, from stainless steel to paper. After exposing these surfaces to the virus, they were tested for the presence of viable viral particles.

They also used feces and urine specimens from three donors, comprising two adults and a child. This was tested to determine the number and viability of viral particles.

The investigators found that the virus remained stable on seven surfaces, namely, plastic, stainless steel, glass, ceramics, wood, latex gloves, and surgical masks, for up to seven days. The dose sufficient to infect 50% of the cells in tissue culture, producing the characteristic cytopathic effect (CPE), termed TCID50, was determined as the measure of the titer of infectious viral particles remaining on the sampled surface or specimen.

On the seven surfaces mentioned above, the TCID50 went down from 105.83 at time zero to 102.06, which implies that the original inoculating titer had come down steeply by 3.8 log10 over one week.

In the fecal suspensions, the virus was found to survive for only 2 hours, 6 hours and 2 days, in the feces of adult 1, adult 2, and the child, respectively. This may mean that the feces of children allow a longer survival time for the virus.

The viral survival in urine was still longer, with infectious viral particles being found in the two adult urine samples for up to 3 days, and in the child sample for 4 days.

The virus titer declined to half rapidly within one hour, with rapid loss of infectious potential. The next half-life was much longer, with a mean of 19 hours. This is described as a two-phase decay. On paper, the virus decayed in one phase, and in feces, it survived for too short a period to allow half-life calculation.

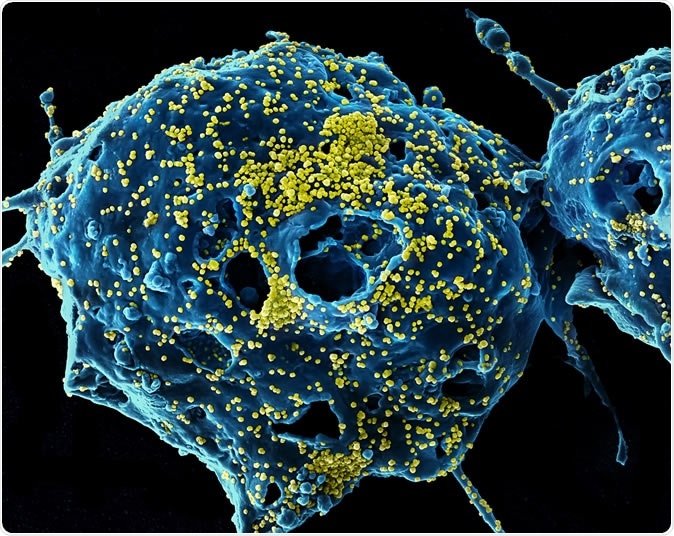

MERS Virus Particles Colorized scanning electron micrograph of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome virus particles (yellow) attached to the surface of an infected VERO E6 cell (blue). Image captured and color-enhanced at the NIAID Integrated Research Facility in Fort Detrick, Maryland. Credit: NIAID

Why is The Study Important?

Given the difficulty in controlling the spread of the virus, it is vital to interrupt routes of transmission. The World Health Organization (WHO) has advised paying attention to cutting off spread not only via respiratory droplets but also contaminated objects, or fomites, and surfaces.

A recent study suggests that COVID-19 patients contaminate their environment quite widely, which could transmit the virus to many contacts. To confirm this, it is necessary to find out how stable the virus is under different conditions. The current study shows the stability of the virus in a variety of environmental conditions and in human excreta. This is the first study to do so.

An earlier study showed that stable virus particles are present on plastic and stainless steel objects or surfaces for up to 3 days. Another paper reported that the virus could remain stable on various surfaces for 2-7 days, with greater stability on smooth surfaces. The current study extends the period of viability to seven days.

The virus titer in the inoculum, and the volume of inoculum, are also important in determining the results of simulation experiments such as those performed to estimate viral stability. The researchers recommend that to achieve comparable results, “a technical specification should be drafted to guide further research into the survival of the newly emergent virus.”

The presence of virus RNA in the feces of COVID-19 patients has been reported in several studies, even after the respiratory samples became negative. The current study showed that the virus remains stable and infectious in human excreta specimens for hours or days.

Virus isolates from feces do not correlate with high viral RNA titers, with only three successful isolations having been reported so far. This is explainable in terms of the short survival of the virus in these samples. The implication is that virus plating should occur as soon as possible from the time of sample collection to maximize the yield.

The researchers say that given the persistence of the virus in the environment and excreta, careful attention to hand hygiene and disinfection measures in toilets are essential to interrupt viral transmission.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources