A new study has shown that COVID-19 patients admitted to the Intensive care unit may be resistant to the naturally occurring anticoagulant Heparin. The study titled, “Heparin resistance in COVID‑19 patients in the intensive care unit,” was published in the latest issue of the Journal of Thrombosis and Thrombolysis.

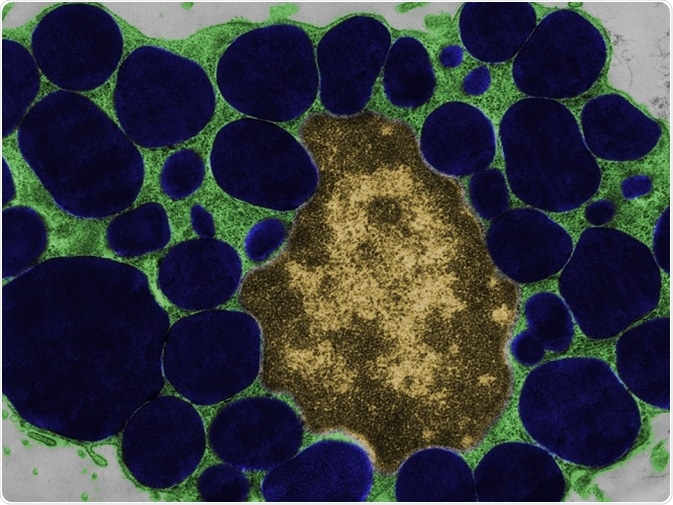

False-color transmission electron microscope (TEM) micrograph of a mast cell (mastocyte) with the cytoplasm (green) full of heparin granules (dark blue). © Jose Luis Calvo/shutterstock.com.

What was this study about?

There is a high incidence of overwhelming inflammation among those infected with the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and often a risk of coagulopathy or increased coagulation of the blood. This is commonly seen among patients who are critically ill and admitted to the ICU for COVID-19. The researchers wrote that the incidence of such “arterial and venous thrombosis” is around 30 percent among the critically ill COVID-19 patients. In these cases, an anticoagulant like Heparin or low molecular weight Heparin (LMWH) is generally used for thromboprophylaxis or prevention of coagulopathy.

The researchers found that several reports show that patients given LMWH for primary thromboprophylaxis may be unresponsive and may go on to develop venous thromboembolism (VTE). The incidence of VTE among patients who have been given LMWH at even high doses is around 56 percent, they wrote. This study was conducted to see the “clinical and laboratory evidence for heparin resistance in patients with COVID-19” admitted at the intensive care unit.

What was done?

For this study the team looked at a group of 69 patients with COVID-19 who were admitted in the ICU at Addenbrooke’s Hospital from 1st March 2020 until 21st April 2020. Among the patients, COVID-19 was confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) swab of the respiratory tract.

Heparin resistance was examined among the patients who received it for anticoagulation. Among the participants in the study, 15 received therapeutic anticoagulation with Heparin (unfractionated Heparin or UFH) or LMWH (Dalteparin). Detailed information was available on 14 of these 15 patients.

Patients who developed VTE were given therapeutic anticoagulation. Heparin resistance was assessed using measures of Heparin required. It was defined as “requiring > 35,000 units of heparin per day for those on UFH”. Among those that received LMWH, anti-Xa (coagulation factor Xa) levels were measured. Expected anti-Xa when on LMWH was defined as a two to four-hour peak level of anti-Xa activity of 0.6–1.0 IU/mL for those on twice-daily dosing of LMWH and > 1.0 IU/mL for those on once-daily dosing of LMWH. To see if coagulation levels as desired was achieved, activated partial thromboplastin ratio (APTR) defined as the activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) was measured. The range desired was 1.5–2.5 when UFH was used.

What was found?

Results showed that heparin resistance was seen in 8 of 10 patients (80 percent), and among the 5 using LMWH, failure to achieve the desired level of anti-Xa activity was seen in all patients (100 percent). The team wrote, “In-vitro spiking of COVID-19 samples from patients in intensive care unit with low molecular weight heparin failed to recover the anti-Xa level as would have been predicted.” The study also revealed that COVID-19 patients have higher levels of factor VIII and fibrinogen and lower levels of antithrombin. This is responsible for the coagulopathies and the resistance to the Heparin.

Conclusions and implications

The researchers wrote, “In this study monitoring the heparin effect with anti-Xa for patients on UFH did not appear to add benefit to monitoring via the APTR.” They found that higher doses of Heparin were needed to ensure the anti-Xa activity of 0.3–0.7 IU/mL. In vitro recovery of anti-Xa activity was also low among these patients, the team wrote. They recall from earlier studies that “after 2500 units of dalteparin, the anti-Xa activity is in ICU patients is approximately half of the value of that in healthy volunteers.” This was corroborated in the present study, they wrote.

The team accepts that this was a small study and is a single-center study. This meant that the results might not be accurate for large populations. Further, all details of the patients were unavailable, and the clinical endpoints and laboratory results were not found for all patients. This study also fails to assess the reason behind the heparin resistance seen among ICU patients.

The team wrote in conclusion that heparin resistance was found among the critically ill COVID-19 patients. They wrote, “Given the resistance to heparin seen; then this could offer some insights into why high rates of thromboprophylaxis failure have been seen in COVID-19 when standard thromboprophylactic LMWH doses are used.” They also called for further studies to look at this and to determine the “optimal thromboprophylaxis in COVID-19 and management of thrombotic episodes.”