Hyperthermia has shown promise in the treatment of cancer in previous studies. Now, in a new study by scientists at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, the researchers tested the effects of a combination of heat and radiation on mini tumors grown in a spheroid, where cells are placed in a three-dimensional structure. The research is published in the journal Scientific Reports.

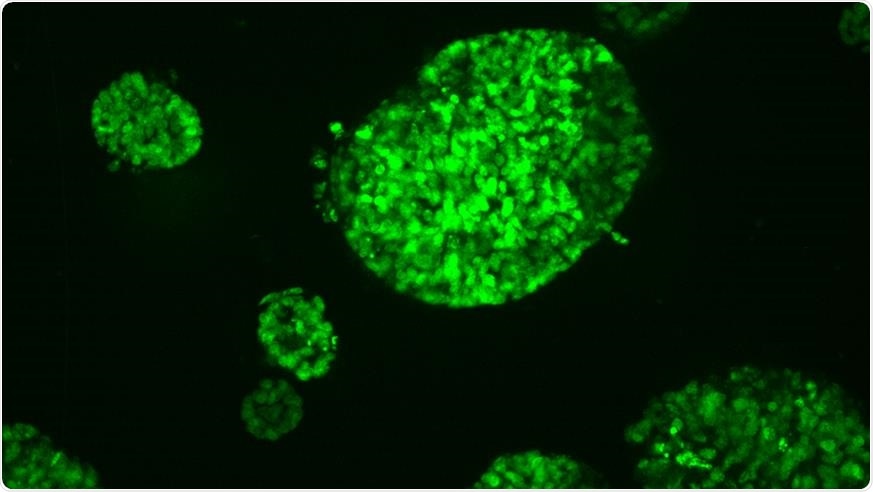

Mini tumours grown from a bowel cancer. Image Credit: The Institute of Cancer Research

Previously, scientists have shown that therapies combining radiation and heat have a different effect on laboratory-grown mini tumors than in lab-grown cancer cells generated more conventionally in a two-dimensional layer.

Traditional cancer treatments include chemotherapy and radiation. Recently, hyperthermia has been a promising new treatment to ward off cancer cells. Hyperthermia, also known as thermal therapy or thermotherapy, is a type of cancer treatment wherein the body tissue is exposed to high temperatures. Studies have shown that heat can damage and kill cancer cells, with minimal injury to healthy and normal tissues.

The therapy involves exposing cells to heat through high-intensity therapeutic ultrasound (HIFU), which is a pioneering technology developed at the ICR. Currently, scientists are exploring the potential of combining hyperthermia and radiation for more effective cancer treatment. Exposing cancer cells to high temperatures make them more susceptible to standard cancer treatments, such as radiation.

The application of heat may elevate the blood circulation to the cancer cells, hence, heightening the amount of oxygen available to them, which will make them easier to kill with radiation.

Using mini-tumors

The ICR is a pioneer in using mini tumors in experiments. In the study, the researchers exposed mini-tumors to a temperature of 47 degrees Celsius, radiation, and a combination of both. They cycled the treatments for standard cancer cells grown in the laboratory for comparison.

They found that the cells in the mini tumors are more resistant to heat than lab-grown cancer cells. Further, they revealed that after being exposed to heat, the cells in mini-tumors were more likely to grow at a faster rate.

The team suggests that this was due to the changes in the environment around the tumor, which made more oxygen readily available to them, hastening growth.

“We suggest that, unlike radiation, which kills dividing cells, hyperthermia-induced cell death affects cells independent of their proliferation status. This induces microenvironmental changes that promote spheroid growth. In conclusion, 3D tumor spheroid growth studies reveal differences in response to heat and radiation that were not apparent in 2D clonogenic assays, but that may significantly influence treatment efficacy,” the team concluded in the study.

The team recommends that further research is needed to determine the best dose of radiation given to patients in combination with hyperthermia.

“We can, however, conclude based on our preliminary study that radiation dose weighting based on clonogenic cell survival analysis alone may be insufficient to predict treatment efficacy of combination treatments since spheroid growth after radiation alone, hyperthermia alone or combined radiation-hyperthermia at the same BEQDs, differed significantly. Thus, more sophisticated biological dose concepts, potentially based on spheroid data, need to be suggested,” the team added.

Cancer global toll

Cancer treatment evolves to help patients combat the killer disease, which is considered the second leading cause of death globally. Cancer took an estimated 9.6 million lives globally in 2018 alone.

The most common cancers in men include lung, prostate, colorectal, stomach, and liver cancer. In women, the most common cancers are breast, colorectal, lung, cervical, and thyroid cancer. Treatments for cancer usually involve surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation.

According to the National Cancer Institute, there is an estimated 439.2 per 100,000 men and women diagnosed with cancer per year in the United States. The number of cancer deaths is about 163.5 per 100,000 men and women each year, based on the data between 2011 and 2015.

Still, the death rate from cancer in the country has declined steadily over the past 25 years, as reported by the American Cancer Society. In 2016, the cancer death rate for both men and women had declined by 27 percent from its peak in 1991. The decline has been tied to better diagnostics and innovative treatments.

Source:

World Health Organization (WHO). (2020). Cancer. https://www.who.int/health-topics/cancer

National Cancer Institute. (2020). https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/understanding/statistics#:~:text=The%20number%20of%20new%20cases,on%202011%E2%80%932015%20deaths).

American Cancer Society. (2020). Facts & Figures 2019: US Cancer Death Rate has Dropped 27% in 25 Years. https://www.cancer.org/latest-news/facts-and-figures-2019.html

Source:

Journal reference: