The novel coronavirus first emerged in December 2019, during the cold season in China. From there, it has spread across the globe, infecting roughly 6.5 million people.

The team of researchers at the University of Sydney has found that a 1-percent decrease in humidity could increase the number of COVID-19 cases by 6 percent. This means that by the time the cold season hits again, the number of cases will increase, sparking another outbreak.

“COVID-19 is likely to be a seasonal disease that recurs in periods of lower humidity. We need to be thinking if it’s wintertime, it could be COVID-19 time,” Professor Michael Ward, an epidemiologist in the Sydney School of Veterinary Science at the University of Sydney, said.

COVID-19 and humidity

The first cases of SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2) were reported in Wuhan City in Hubei Province, China, in December 2019. Since then, COVID-19 has been reported throughout the world, resulting in a pandemic of over 6.51 million infections, with a death toll of more than 385,000.

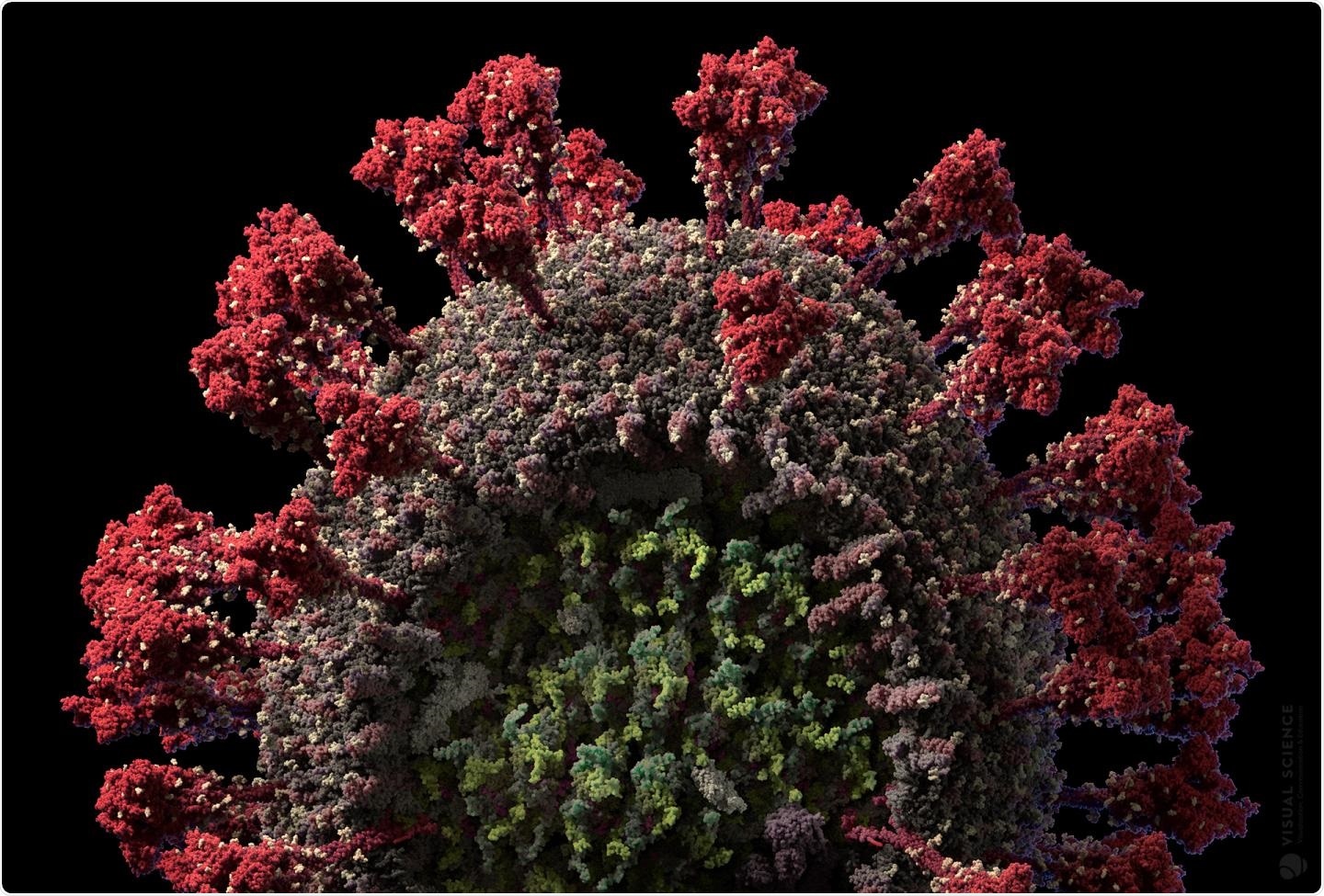

A scientifically accurate model of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Image Credit: Visual Science

The study, which was published in the journal Transboundary and Emerging Diseases, highlights the link between climate and COVID-19. Studies in the past have provided a connection between climate and the occurrence of COVID-19 cases in locations such as China and Hong Kong.

The team notes that the pandemic ravaged many countries, such as China, Europe, and North America, during the winter season, with skyrocketing cases. The team wanted to see if the connection between COIVD-19 cases and the climate was different in Australia in late summer and early autumn.

They revealed that lower humidity is the primary driver of COVID-19, instead of cold temperatures.

“It means we may see an increased risk in winter here when we have a drop in humidity. But in the northern hemisphere, in areas with lower humidity or during periods when the humidity drops, there might be a risk even during the summer months. So, vigilance must be maintained,” Prof. Ward said.

Why humidity?

The researchers shed light on one biological reason why humidity is an essential matter in the transmission of airborne viruses.

Prof. Ward emphasizes that when the humidity is lower, the air is dry, and it makes aerosols smaller. When they are smaller, they can be suspended in the air longer, which can expose many people to the virus.

To arrive at their findings, the team evaluated 749 locally acquired cases of COVID-19, who were from New South Wales (NSW) and Greater Sydney from Feb. 26 to Mar. 31. The team matched the postcodes of the patients with the nearest weather observation station.

The team conducted daily meteorological recordings, including rainfall, temperature, and relative humidity. They also estimated the median values for each day for the period January to March 2020. From there, they found that the number of cases increases as the level of humidity decreases.

When there is low humidity, there is not much water vapor in the air. When someone coughs or sneezes, the aerosolized particles in the air. These aerosol particles can be inhaled and can cause lung irritation.

Prof. Ward urges every resident to be cautious and vigilant even if the number of cases had declined over the past months. Still, testing and contact tracing must continue until there are no more cases.

“In conclusion, under the conditions of high temperature in the Southern Hemisphere summer, our study provides evidence that lower relative humidity is associated with COVID‐19 cases. It also suggests that all countries need to maintain vigilance for COVID‐19, even during the summer months,” the team concluded.

Further research is needed to determine if the scenario is the same in other countries. This can help guide health officials to decide on easing restrictions and preparing for a potential second wave of the virus.

Sources:

Journal reference: