On the other hand, the researchers say, tolerance to the pathogen is another mechanism that prevents organ damage and hyperinflammatory responses to the virus. This is described as the physiological pathway by which the body limits the generation of harmful inflammatory chemicals as well as of chemokines produced as a result of the detection of the virus by the body’s immune cells.

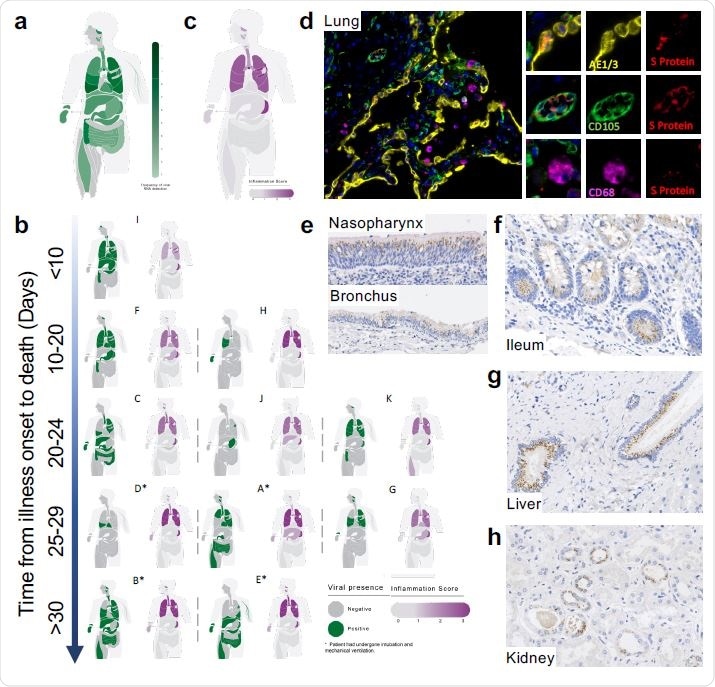

Mapping SARS-CoV-2 organotropism and cellular distribution in fatal Covid- 19 in relation to local inflammation. Distribution of SARS-CoV-2 RNA for all patients was determined by multiplex PCR (A; color intensity denotes the frequency of detectable RNA, dotted line on legend denotes maximal frequency within the patient cohort) (n=11). Distribution of individual patient viral RNA presence within organs plotted against time interval between illness onset and death compared with a semi-quantitative score of organ-specific inflammation for each patient (B). The severity of acute organ injury was assessed semi-quantitatively (0-3; no acute change (0) to severe organ injury/histological abnormality (3)) with aggregate scores visualized (C; n=10-11 per organ/tissue site). Cellular distribution of SARS-CoV-2 S protein was evaluated by immunohistochemistry and multiplex immunofluorescence on FFPE tissue demonstrating its presence within the alveolar epithelium and rarely in macrophages and endothelium within the lung parenchyma (D) nasal mucosal and bronchial epithelium (E), as well as small bowel enterocytes (F), distal biliary epithelium within the liver (G) and distal renal tubular epithelium (H). Representative images from n=4 PCR-positive patients.

Inflammation of the Lung and Fatality in COVID-19

It is established that severe or fatal cases of COVID-19 are linked with the occurrence of hyper-inflammation, which is a cause of organ damage and death. In most cases, fatal COVID-19 is the result of reduced oxygenation of blood below the critical threshold at which it no longer supports function and life. Recent studies have demonstrated the positive role of dexamethasone, a commonly available corticosteroid, in blunting the edge of this inflammatory response and preventing many deaths.

The inference is that lung inflammation is a fundamental cause of death. This, in turn, suggests that tolerance is probably crucial in promoting recovery from COVID-19. It does not, however, show the cause of such inflammation – is it direct injury or the result of an independent and abnormal immune process?

While COVID-19 is an illness of the respiratory tract, recent studies show that the virus infects many tissues outside the lung. The unsolved issue is whether these organs are also injured or inflamed, as shown by histological evidence and clinical features.

The Study: Tissue-Specific Infection and Response in COVID-19

The current study aimed to outline how different tissues are affected in fatal cases of COVID-19, which tissues harbor the virus, the features of inflammation in different tissue, and how the presence of the virus is related to the local and systemic inflammation and organ injury in every part of the body.

The first part of the study examined the presence of the S protein in different tissues that contained the viral RNA. They found this protein was present in the epithelium of the respiratory tract, the gut, the liver, and the kidney. It was rarely found in macrophages and endothelium within the lung parenchyma, nasal mucosal and bronchial epithelium, small bowel enterocytes, distal biliary epithelium within the liver or distal renal tubular epithelium.

The occurrence of the viral protein in patches within the alveolar epithelium of the lungs agrees with the hypothesis that the virus was probably aspirated from the upper respiratory tract. Conversely, outside the lung, large areas of tissue were found to contain the S protein, with uninfected stretches between them. These are called foci of infection. They represent the spread of the virus from one cell to the next.

Organ Infection Not Linked to Direct Injury

The researchers describe most organs as uninflamed or little inflamed, while evidence of earlier illness was often present. The higher the systemic illness, the worse was the injury to the organ. Thus, patients on the ventilator often had acute tubular necrosis of the kidney.

The presence of the virus in tissues other than the lung was not a measure of the intensity of inflammation or of acute damage to these organs, such as the heart, liver, intestine, or kidney.

Virus Does Not Directly Cause Lung Injury

Even in the lung, the presence of the virus did not relate to pulmonary inflammation in the same areas. Both infected and uninfected areas showed diffuse alveolar damage and bronchopneumonia or appeared utterly normal in some cases.

Other findings included lung clots, mostly mixed, occurring in both small and big vessels. Patches of vasculitis featuring the infiltration of mononuclear cells were found, mostly in the intima (the innermost coat of an organ). Inflamed vessels in these patients did not show the presence of the S protein.

Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) has been used for transcription studies on T cells and resident lung macrophages. These show higher numbers of CD8 T cells with fewer resident lung macrophages but may reflect only luminal pathology. The current study, therefore, looked at the phenotypes of the immune cells within whole lung tissue, finding the most striking increase in immune cells to be within the lung parenchyma and not within or around the blood vessels. The cells showing the most significant increase were mononuclear cells and certain monocyte lines, then CD8+, and finally CD4+ T cells.

Reticulo-endothelial cells were also found to be severely affected within the spleen and lymph nodes.

Injury Due to Inflammatory Damage

The researchers point out that their observations do not correlate with organ damage occurring as a result of a local inflammatory response to the virus since the damage does not occur at all sites of infection nor is it related in time to the occurrence of infection. Instead, the evidence of viral infection is seen in many tissues in fatal COVID-19 for up to 42 days from the earliest symptom.

Again, viral RNA is found in the kidney, liver, and intestine, but there is no sign of injury or inflammation. Thus, viral infection in COVID-19 does not cause localized inflammatory responses. This is true of the presence of the virus in the lung as well. The presence of vasculitis in many cases of COVID-19 was confirmed, but this was not linked to direct viral injury.

Macrophages and Plasma Cells

The observation of iron-laden macrophages supports the finding that higher ferritin levels in serum indicate a poorer outcome. These occur in the inflamed vessels as well as the parenchyma of the lung, and reticuloendothelial tissues. More research is needed to understand their role, whether in antiviral defenses, helping with tissue healing, or as part of the immune response but having a deleterious effect.

The lung and reticuloendothelial tissues also showed marked abnormalities in plasma cells, with an abnormal expansion of this cell type, as well as atypical shape and form. The study draws attention to the need to understand the role played by both iron-laden macrophages and plasma cells in COVID-19 severity, to help develop therapies targeting these factors.

Conclusion

The study concludes: “Given the recent discovery that immunosuppression with dexamethasone prevents death in severe Covid-19, our observations support virus-independent immunopathology being one of the primary mechanisms underlying fatal Covid-19. This suggests that a better understanding of noninjurious, organ-specific viral tolerance mechanisms, and targeting of the dysregulated immune response merits further investigation.”

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Dorward, D. A. et al. (2020). Tissue-Specific Tolerance in Fatal Covid-19. medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.02.20145003. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.07.02.20145003v1

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

Dorward, David A, Clark D Russell, In Hwa Um, Mustafa Elshani, Stuart D Armstrong, Rebekah Penrice-Randal, Tracey Millar, et al. 2020. “Tissue-Specific Immunopathology in Fatal COVID-19.” American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, November. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202008-3265oc. https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/10.1164/rccm.202008-3265OC.