The COVID-19 pandemic caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has infected over 16.67 million individuals and caused over 659,000 deaths around the world. Commonly the deadly virus and its impact are measured by the case fatality ratio (CFR).

This study was funded by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation and the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program - project EpiPose.

What was this study about?

Researchers led by Anthony Hauser from the University of Bern, Switzerland, said that it is vital to understand the risk of mortality due to COVID-19 to predict the prognosis or outcome of the infection as well as for the planning of healthcare capacity and its preparedness. It is also important as a tool to predict the outcome of the pandemic.

The team explained that the case–fatality ratio (CFR) could be estimated by calculating the total numbers of reported cases and reported deaths. They write, "...it can be a misleading measure of overall mortality". They wrote that symptomatic case–fatality ratio (sCFR) is essentially the proportion of persons who have been infected and show symptoms who go on to die throughout their SARS-CoV-2 infection. This is said to be clinically relevant in assessing the prognosis or outcome of the infection as well as estimating the healthcare requirements. The infection– fatality ratio (IFR), on the other hand, is the proportion of individuals infected with the SARS-CoV-2 who will eventually succumb to the infection. This is said to be the "central indicator for public health evaluation" when estimating the overall impact of an epidemic on a given population wrote the researchers.

The purpose of this study was to use mathematical models to simulate the transmission process of the SARS CoV-2 based on the surveillance data and from these estimate death rates due to the virus. They also adjusted the results for various factors to calculate the CFR as well as the symptomatic case–fatality ratio (sCFR), and the infection–fatality ratio (IFR). This was done in different regions in China and across Europe.

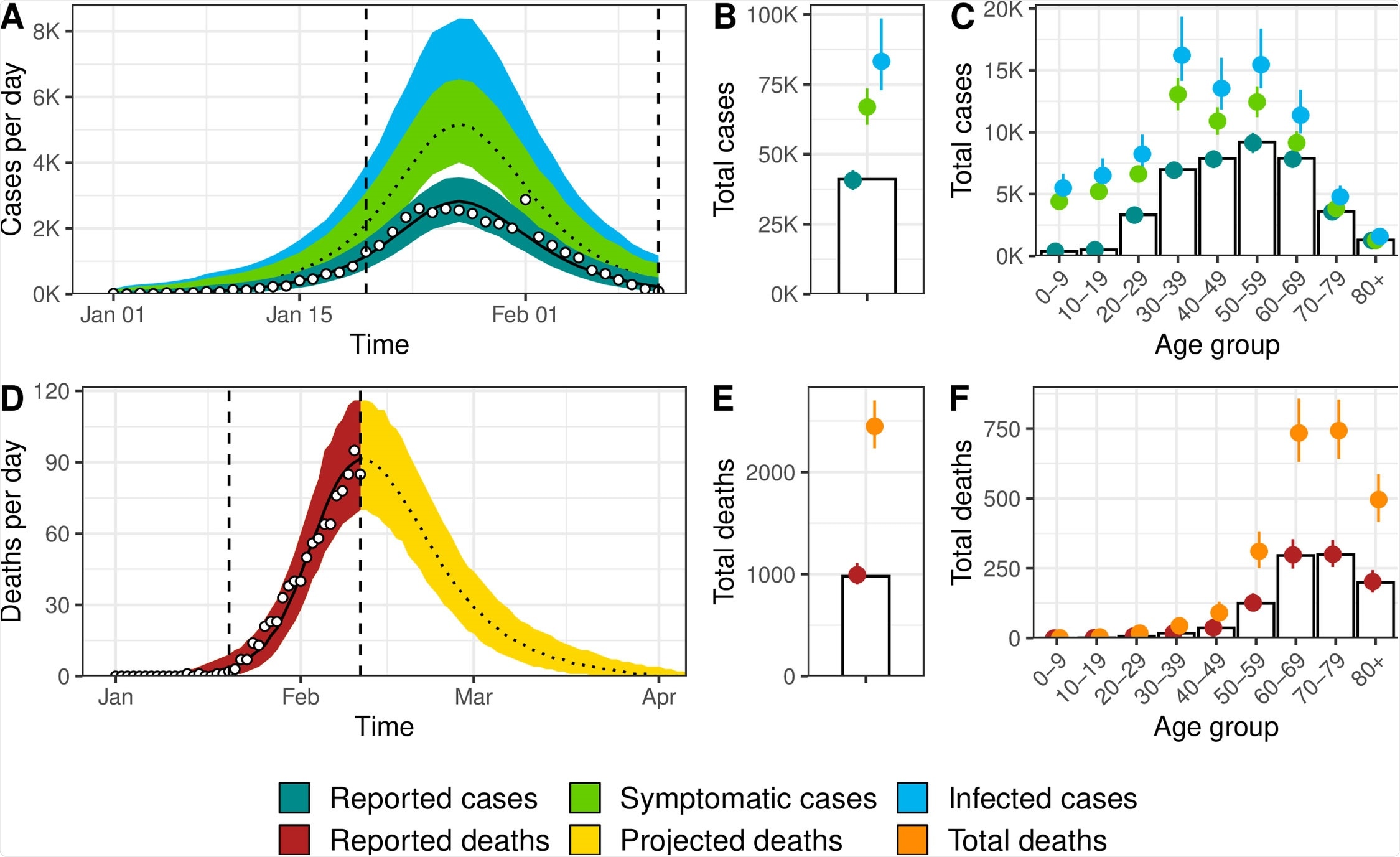

Model fit for Hubei, China, of (A) incident cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection by date of symptom onset, (B) total cases, (C) age distribution of cases, (D) incidence of deaths, (E) total number of deaths among individuals infected until 11 February 2020, and (F) age distribution of deaths. White circles and bars represent data. Lines and shaded areas or points and ranges show the posterior median and 95% credible intervals for six types of model output: reported cases, symptomatic cases, overall cases (i.e., symptomatic and asymptomatic cases), reported deaths until 11 February 2020, projected deaths after 11 February 2020, and overall deaths. SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

What was done?

For this study, the team developed a model in which they stratified the data according to age. Their model was called the "susceptible-exposed-infected-removed (SEIR) compartmental model." It helped the researchers to define the dynamics of the spread of the infection and the risk of death or mortality during the COVID-19 pandemic. They wrote that they accounted for two biases "preferential ascertainment of severe cases and right-censoring of mortality."

Their data was gathered from Hubei Province, China, and also applied to six regions in Europe including, "Austria, Bavaria (Germany), Baden-Wu¨rttemberg (Germany), Lombardy (Italy), Spain, and Switzerland."

What did they find?

From their modeling, the team found that the case fatality rate was 2.4 percent in Hubei while the sCFR was 3.7 percent, and IFR was 2.9 percent. They wrote that with time the measures of mortality changed.

Coming to the six regions of Europe, the CFR was widely different. On the other hand, the sCFR and IFR, when adjusted for the biases, were more or less similar in the six regions. The range of IFR, for example, was 0.5 percent in Switzerland and 1.4 percent in Lombardy, Italy.

The risk of death rose with age in all regions with those over 80 years of age having an IFR between 20 percent in Switzerland and 34 percent in Spain.

Implications of the study

The authors have proposed a comprehensive method to estimate the SARS-CoV-2 mortality from the available surveillance data. They wrote that CFR might not be a good predictor of the overall risk of death due to SARS-CoV-2 and recommend that it should not be used for policy-making decisions and comparison across settings.

This study also reveals there are differences in IFR in different geographical regions, and the total size of the epidemic in different areas can be estimated by estimating the region-specific IFR. The team wrote in conclusion, "The sCFR and IFR, adjusted for right-censoring and preferential ascertainment of severe cases, are measures that can be used to improve and monitor clinical and public health strategies to reduce the deaths from SARS-CoV-2 infection."

The team called for further long term studies to see if these parameters and subsequent policies could help reduce the risk of death from SARS-CoV-2, especially among older individuals. These studies can also explore the reasons behind the differences in mortality rates due to the pandemic seen in different geographical regions around the world.