With the rapid and extensive spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, the USA witnessed an almost universal closure of schools in March 2020. Now, after months of enforced online schooling, federal authorities are impatient for schools to re-open. However, how should this be done without endangering the lives of teachers, administrative and other non-teaching staff, and students at school, and parents/other family members at home?

Though children typically have milder and shorter symptoms relative to adults, for that very reason, they are likely to cause asymptomatic spread, making the detection and measurement of transmission between children very difficult. While some studies suggest that the rate of transmission with each contact between children is low, the number of contacts is much higher than in other age groups. This is reflected in the current model, which also accounts for the reportedly higher viral load in the nasopharynx in young children.

However, it is difficult to work out proper strategies that do not lead to longer working hours for teachers or pen up children in overcrowded classrooms. Moreover, with shifts in school timings, parents or caretakers who work will face difficulties in bringing in and picking up the children.

However, indefinite school closure is not an option since even with the visible effects of this measure on COVID-19 incidence in some states, both educationists and parents fret about the damage it will apparently cause to the educational development of children once re-opening is successfully carried out. Strategies must be tuned to allow subsequent smooth school attendance while not increasing the social burden unduly.

Some schools that re-opened had to close within a week due to exposure to confirmed COVID-19 cases. Thus, both guidelines on when to re-open, and plans on how to re-open, are alike necessary. The current study aims to describe a simple model that will help understand variations in infection rates in both adults and children with different re-opening approaches and criteria.

The researchers base their analysis on an age-stratified assignment of all those in a given school scenario into either one, two, or three groups. The age-based classification creates a cohort of adults and another of children. Each cohort is ascribed to homogeneous disease attributes.

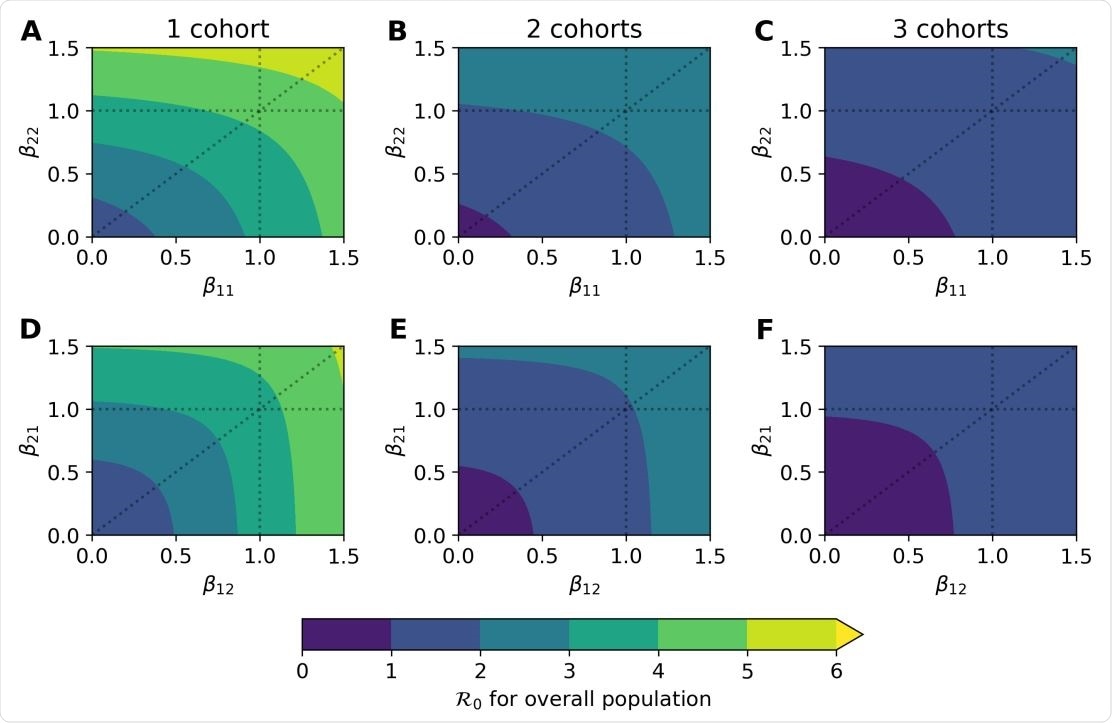

Predicted R0 under various density and rotating cohort scenarios. Results are based on a latent period of 3 days (σ1 = σ2 = 1/3) and an infectious period of 4 days (γ1 = γ2 = 1/4). We also assume weak interaction between cohorts (αk` = 0.05 when k 6= `). As the color gradient changes from purple to blue, R0 changes from < 1 to > 1. (A–C) Varying values of β11 (child-to-child) and β22 (adult-to-adult) rates, assuming transmission between both is equal (β12 = β21 = 0.5). (D–F) Varying values of β12 (child-to-adult) and β21 (adult-to-child), assuming transmission within adults is dominant (β11 = 0.1 and β22 = 0.5).

Using Cohorts to Reduce Student Density

The aim of creating more than one cohort is to reduce student density in the classroom. Thus, these will help to analyze how re-opening at full capacity compares with re-opening at half-capacity with the remaining students continuing with remote learning (parallel cohort strategy), or rotating cohorts between alternate weeks or three weeks. These are rotating cohorts. The researchers paid particular attention to the policy declared by California Governor Gavin Newsom for schools in his state.

The study shows that at half capacity, by either of the last two methods, schools will probably be able to control viral spread more significantly than more direct methods applied without physically reducing student density, such as masks, hand sanitation, and desk shields, among others. Additionally, when there are fewer contacts, doing regular rapid tests for the virus is capable of producing significantly later outbreaks of disease, despite the relatively low sensitivity.

Re-opening Under Stopping Guidelines

The recent guidelines by California’s Governor Newsom emphasize that schools should close whenever there are 5% infected individuals in one school over a period of two weeks. The current study uses this to frame a stopping rule on a cumulative 5% prevalence.

Here, testing undertaken at the beginning of the day, and infected individuals are then isolated at once. Thus, the researchers say, “Under the assumption of a 20:1 student-staff ratio, a school with 1,000 students would need approximately 53 cases in a 14-day period to meet the closure criterion.” That is, unlike the California criterion of 5% cases in any 14-day window, the current study requires 5% cases over 14 days from the start of testing.

Single Cohort + Regular Testing + Closure Thresholds

In most cases, the rotating cohorts and parallel cohorts take about the same time to reach the 5% mark, partially due to the testing scheme. However, the real-time scenario is one of test shortages and personnel limitations. Taking these into account, the researchers estimated the effect of a less sensitive but more rapid test. They found on simulations of a single cohort that if the 5% threshold is observed, the rate of infection may diminish from 80% to 55% over six months in a high transmission scenario, with a sensitive test.

However, even if the detection rate of the test is only 50%, the stopping or closure date will be earlier but still far later than if no testing is done. Thus, they emphasize, “Re-opening with a surveillance program in place may provide 10 to 12 weeks of continuous instruction with low infection risk.”

If parallel cohorts are opted for, the single cohort has a slower rise in infection and later school closure than two parallel cohorts. The reduction of contact density between the online and in-person cohorts leads to a more extended period of instruction for 18-22 weeks than when the school is at full capacity (10-12 weeks). Interestingly the number of infections in the remote cohort is higher than in the in-person contact even though the rate of transmission between children in the former is only a tenth of that in the latter. This discrepancy is because the latter cohort is only reckoned to be tested under the school program, while the remote learning cohort will probably be tested at some point.

This 5% criterion, if applied without any mitigation steps whatever, in a school with high viral spread, and at full capacity, would trigger closure within a month, they estimate. However, when preventive measures are in place, it may take weeks to months to build up to the 5% mark. In fact, if student density is maintained at a low level, and if other mitigation measures are employed effectively, the threshold may never be reached.

Implications

The researchers say, “Reducing the number or density of contacts produces a larger effect than diminishing the transmission rate per contact.” These findings should help guide the shaping of public health policies regarding school re-openings. Using single cohort strategies, with testing being foundational even if imperfect, and providing a failsafe mechanism in the form of complete closure of the school if cumulative incidence passes 5% will help curtail disease spread and prevent the occurrence of a major outbreak after re-opening, allowing at least three months of instruction before closure.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources