Scott Boyd and colleagues say the finding that severely ill ICU patients had strong antibody responses to the virus suggests that it is not an impaired or delayed humoral response that is responsible for more severe disease.

Compared with inpatients, outpatients and asymptomatic individuals had much weaker, short-lived antibody responses that started to decline around one month following diagnosis. However, this does not necessarily mean all immunity would be lost, says the team.

One implication of the finding, however, is that seroprevalence studies might eventually underestimate the proportion of individuals that have previously been infected.

Results from clinical trials investigating re-exposure to SARS-CoV-2 among previously infected and recovered individuals will be needed to establish which immunological assays might best determine the most accurate correlates of protection against re-infection, say the researchers.

A pre-print version of the paper is available on the server medRxiv*, while the article undergoes peer review.

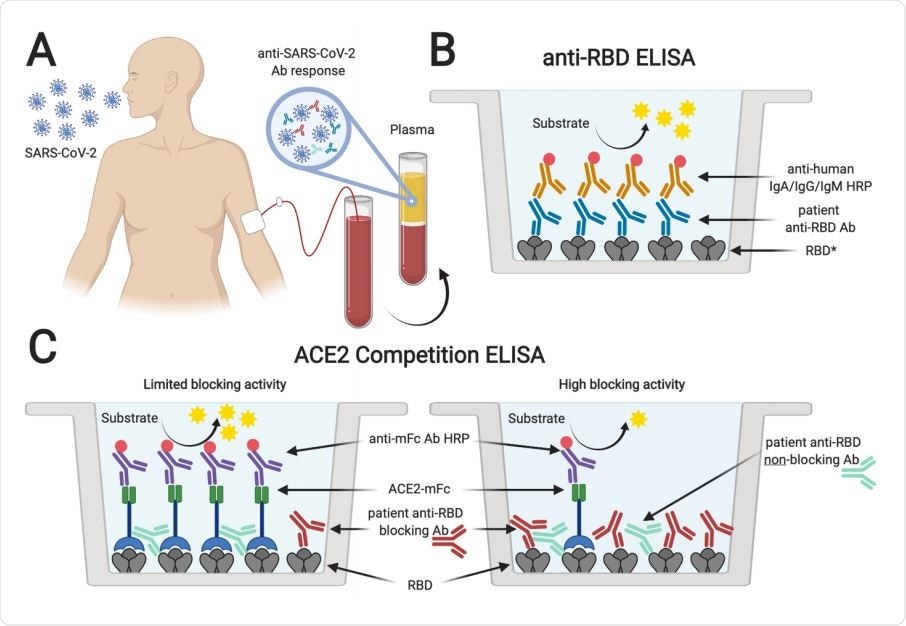

Serological testing of plasma from SARS-CoV-2 PCR+ individuals. Plasma samples from SARS-CoV-2 rRT-PCR-positive individuals (A) were analyzed for the presence of antibodies binding to SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD (B). *Plasma was also tested for antibodies specific for SARS-CoV-2 S1 and N protein, and SARS-CoV RBD. In addition, samples were tested for antibodies blocking the interaction of ACE2 and RBD in an ACE2 competition ELISA (C). Absence or limited presence of anti-RBD antibodies resulted in ACE2 binding to RBD and increased ELISA signals, whereas the presence of blocking antibodies prevented binding of ACE2, resulting in lower ELISA signals (created with biorender.com).

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Devastating effects of rapidly spreading COVID-19 pandemic

Since the first cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) were identified in Wuhan, China late last year, the causative agent – SARS-CoV-2 – quickly became pandemic and has had devastating health and socioeconomic impacts globally.

Following infection, clinical presentation ranges from asymptomatic or mild respiratory disease (in the majority of cases) to severe pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, respiratory failure, and death.

Immune system responses could be key in determining patient outcomes

Immune system responses following infection could be one of the main determinants of disease progression and patient outcomes.

The main surface structure that SARS-CoV-2 uses to bind and gain entry to host cells is the spike glycoprotein, which attaches to the host cell receptor angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2).

The receptor-binding domain (RBD) of this spike protein is probably an important target for neutralizing antibodies. The spike protein and its RBD are, therefore, of significant interest in the development of serological and neutralization assays for the surveillance of public health.

Such tests would help researchers more accurately determine infection rates, death rates, and the development of herd immunity, as well as identify convalescent patients. They could potentially serve as donors of protective plasma.

The challenges faced

Key factors that need to be established include the extent to which antibody responses protect against re-infection and the duration of any protective effect. As trials of potential vaccines proceed, it will be important to compare vaccine-induced immune responses with those induced by viral infection if correlates of immunological protection are going to be properly understood.

To address this need, the researchers have comprehensively analyzed serological responses to SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and its RBD among 210 individuals, including 40 hospitalized patients receiving ICU care and 170 outpatients and asymptomatic individuals. The team analyzed the antibody responses using a panel of SARS-CoV-2-specific antigens and a novel competition ELISA to test the effectiveness of RBD-specific antibodies at blocking the binding of ACE2.

What did the study find?

Increasing levels of antibodies in the blood strongly correlated with increasing blocking activity against the ACE2-RBD interaction. Increased antibody levels also negatively correlated with detectable viral load in the blood, which would be consistent with a humoral immune clearance of the virus, says the team.

This increased antibody response and ACE2 receptor blocking were most prominent in patients who were severely ill.

The novel ELISA test detected blocking of the RBD-ACE2 interactions in 68% of inpatients and 40% of outpatients.

High levels of the antibody immunoglobulin G (IgG) were sustained among inpatients for at least two months, say, Boyd and team, although not all patients were observed for this long.

“The timing of the onset of IgG responses and the finding that severely ill COVID-19 patients who required ICU care developed high anti-RBD antibody titers indicates that delayed or impaired production of virus-specific antibodies relative to the onset of symptoms does not explain differences in disease severity,” write the researchers.

By contrast, outpatients and asymptomatic individuals had short-lived plasma antibody responses, with antibody levels peaking at about one month after diagnosis before rapidly declining.

“One implication of these results is that seroprevalence studies may, over time, underestimate the proportion of the investigated population which has been previously infected with SARS-CoV-2,” said Boyd and colleagues.

A short-lived antibody response does not necessarily mean no future protection

The team says the short duration of plasma antibody responses among asymptomatic individuals and outpatients does not necessarily mean they will lose all immunity against re-infection since local antibody responses in the airways could be protective on re-exposure.

Furthermore, even if antibody levels had declined to undetectable levels, re-infection might induce memory B and T cell responses that could be protective.

“Clinical trial results from patients with known re-exposure to SARS-CoV-2 after recovery from initial infection will be needed to determine which serological or other immunological assays provide the most accurate correlates of protection from re-infection,” conclude the researchers.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources