The coming of autumn in temperate countries has led to fears that the declining incidence of COVID-19 is about to reverse its trend, as the seasonal rise in influenza and other respiratory viruses begins to kick in.

NPIs and Non-COVID-19 Respiratory Viruses

The COVID-19 pandemic in the cold countries began in January 2020, which was also the peak season for influenza and other seasonal respiratory viruses. These share a common route of transmission, mainly respiratory droplet and contact transmission. Earlier, there was great concern that if multiple outbreaks of these viruses co-occurred, the economic slump, as well as the healthcare system overload, could intensify further.

The rapid spread of SARS-CoV-2 between populations worldwide led to the implementation of a slew of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) aimed at containing the virus. Many involved the whole population, whether a lockdown, shelter-in-place, school and college closures and bans on stores. Face masks were recommended for wear in public spaces along with strict maintenance of physical distance during social interactions outside of one's household and living space, along with handwashing and general hygiene practices.

Multiple research papers from over the world showed that these measures reduced the annual incidence of seasonal respiratory viral illnesses at the same time, as compared to earlier years. The current study aimed to measure the influence of these NPIs on other respiratory viruses, specifically influenza A, influenza B, and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). The study included two large U.S. academic centers in Atlanta, Georgia, and Boston, Massachusetts, covering the period from January through May 2020.

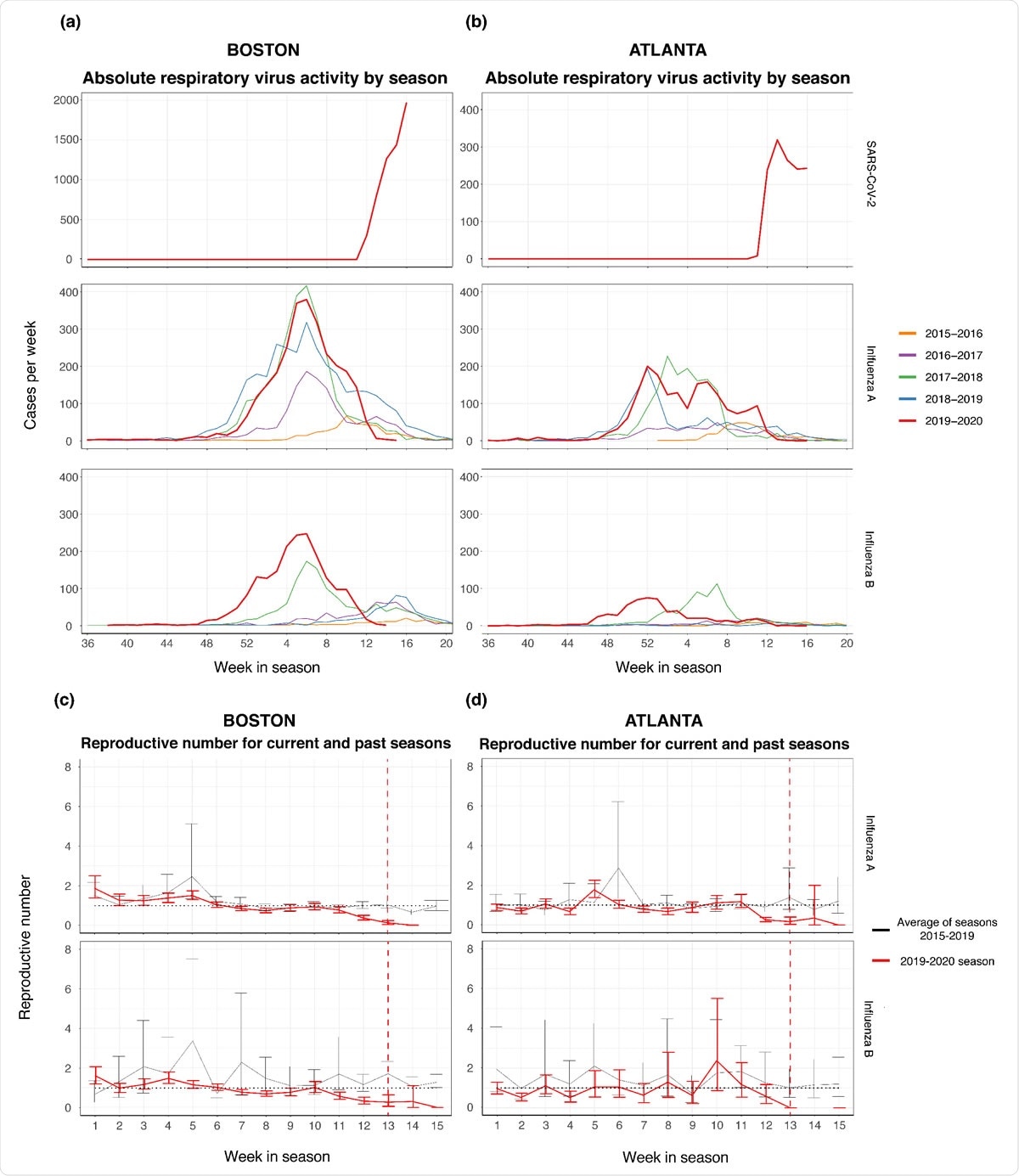

Cases per week of influenza A and Band SARS-CoV-2 of seasons 20 15-2020 in the MGB Healthcare systems in Boston (panel A) and in the Emory University in Atlanta (panel B) by week of respiratory virus season. Note the change in y-ax is scale for Boston SARS-CoV-2 cases (panel A). Comparison of the reproductive number over time, R,, for influenza A and B in prior seasons (the average of the 20 I 5-201 6 through 20I 8-20 19 seasons, as depicted by the black line) versus the 20 19-2020 season as depicted by the red li ne, for Boston (panel C) and Atlanta (panel D). The black dotted horizontal line denotes R, of 1.0. The red dotted vertical line represent the approximate date when NPls were initiated in Atlanta and Boston (week 13).

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Reduction in Case Number and Rt

The researchers used the medical records of all adults tested for these viruses over the last five seasons at these two centers, about 154,000 individuals overall. The season explored was from September through May of the following year, 22 weeks in all. All tests involved nasopharyngeal swabs tested for the above viruses, with a small group being tested for SARS-CoV-2 using oropharyngeal swabs and samples from the lower airway.

They found that the total number of influenza A and B cases, RSV, and SARS-CoV-2 per week per season dropped dramatically in the 2019-2020 season. The reproductive number for each pathogen over time, Rt, defined by the ratio of the number of new positive cases in one week to the number of positive cases in the previous week, was also estimated.

They found that in Atlanta, influenza A infections had a declining Rt below 1.0 on week 12 of the 2019-2020 season. In contrast, it failed to drop below 1.0 before week 15 in the last five years. Interestingly, this coincides with the detection of the first COVID-19 case in this city, in week 11, which led to restrictions on social gatherings and stay-at-home orders in week 12-13.

For influenza B, the drop in cases led to almost zero cases each week after week 13, while in the previous years, the Rt fell below 1.0 only after week 15. For RSV, the Rt fell below 1.0 only at week 13 vs. week 14 in earlier seasons.

These trends were seen in Boston, where influenza A Rt fell below 1.0 on week 7 and near-zero at week 14, whereas in earlier seasons, it fell below 1.0 consistently only after week 15. With influenza B, the Rt was below 1.0 at week 11 vs. week 15 in previous seasons. The Rt for RSV fell below 1.0 between weeks 12-15 in the current season, but this never occurred in previous seasons.

The researchers conclude, "The implementation of NPIs was a critical factor in reducing the spread of SARS-CoV-2 globally." This is supported by the evidence of a declining Rt and case number for three seasonal respiratory viruses in two cities in the U.S., which are far away from each other. By reducing the opportunities for these viruses to be transmitted, NPIs also played an important role in controlling these respiratory pathogens.

These findings will help estimate the chances that a given respiratory infection has COVID-19 vs. the flu and in screening for COVID-19. The study also shows the importance of physical distancing in reducing seasonal respiratory virus-related morbidity and mortality.

Implications

In the coming season, the changing patterns of infection with these four viruses will become more apparent. The already apparent reduction in flu cases over the past season has impacted the ability to predict the circulating strains in the coming flu months. The international travel restrictions will also play a part in these changes over time, requiring further study to understand the pandemic's full impact on the spread of the flu and its target population.

Another factor that cannot be excluded is the lower number of physician consults for the flu and other respiratory viruses during the pandemic season and lower testing for such diagnoses overall, given the need to conserve resources for COVID-19 testing.

The researchers also raise the possibility of "respiratory virus interference," in which one viral outbreak interferes with the dynamics of another, perhaps due to non-specific immunity against multiple respiratory viruses elicited by one acute infection.

The study concludes, "The data demonstrate that NPIs are likely effective in reducing both influenza and SARS-CoV-2 transmission."

This could help shape effective policies to deploy NPIs, both to avoid misdiagnoses with multiple circulating viruses and an overwhelming burden on the healthcare system.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources