People who contract the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus that causes the coronavirus disease (COVID-19), often develop respiratory symptoms such as fever, cough, dyspnea or difficulty of breathing, and bilateral changes on chest imaging.

With the cold season coming in the northern hemisphere, there will be an increase in people developing COVID-19 and pneumonia, an infection in one or both lungs where the air sacs fill up with fluid or pus. It is challenging to determine if patients have a bacterial respiratory co-infection along with COVID-19. This difficulty may lead to the over-prescribing of antibiotics in patients with the coronavirus infection.

Now, a team of researchers at the University of Rochester Medical Center aimed to determine antibiotic prescribing rates and risk factors for antibiotic prescribing in hospitalized patients. They found that almost one-third of patients received more than one course of antibiotics.

Antibiotic Prescribing Trends

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

The study

The study, which appeared on the pre-print server medRxiv*, tackled how COVID-19 patients are treated in hospitals with antibiotics. The study involved antibiotic prescription trends in patients with confirmed COVID-19 at three hospitals within the University of Rochester Medical Center.

The team included patients who are 18 years and above admitted between March 1 and May 31, 2020, and treated for Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-confirmed COVID-19. Those without symptoms were excluded from the study.

Data were collected until June 30, including information on the patients’ laboratory findings upon admission, microbiological data, imaging, antibiotic data, death, and re-admission within 30 days.

Study findings

The research aimed to determine antibiotic use rate among patients admitted due to COVID-19, including risk factors tied to antibiotic use.

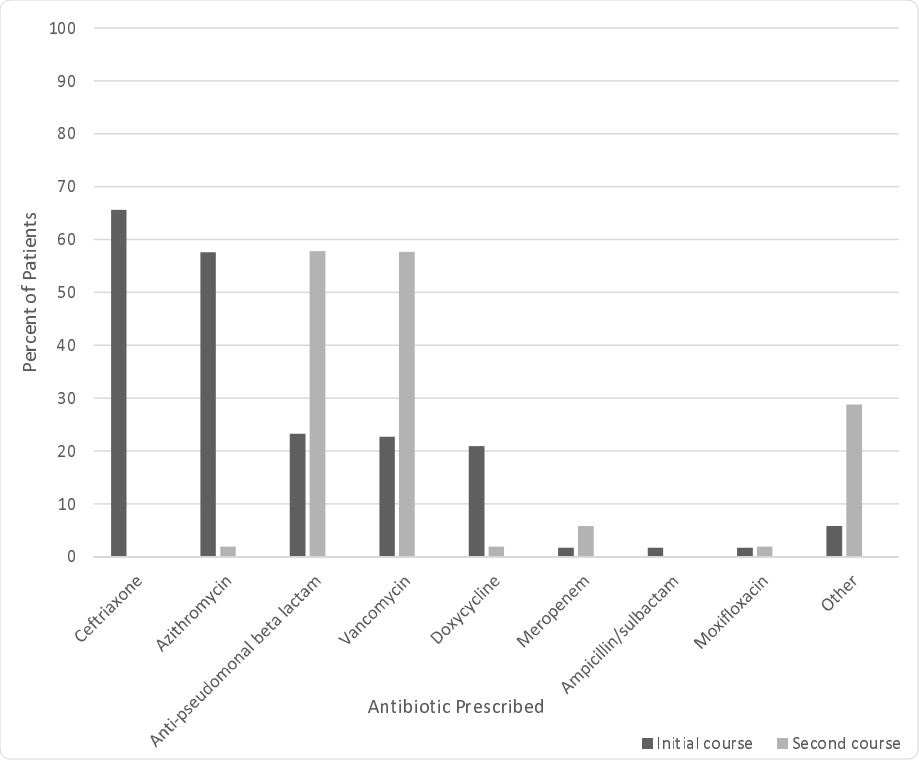

In the study’s final analysis, a total of 198 patients were included, wherein 83 percent received at least one course of antibiotics, even if there are low rates of microbiologically confirmed infection. Further, one-third of 30 percent received more than one course of antibiotics. From all these patients, the team was only able to get 32 percent of cultures.

The team also found that the risk factors associated with using more than one course of antibiotics include serious illness, admission to the intensive care unit, increased hospital length of stay, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and mechanical ventilation.

The rates of antibiotic prescription were markedly higher in patients admitted to the ICU who required oxygen support. Also, those with ARDS were more likely to be prescribed more antibiotics. Of all the patients who died within 28 days, 92 percent received antibiotics.

“In our study, we reported microbiologic data throughout hospitalization, and even during multiple admissions whereas these two previous studies only reported the first 48 hours. This likely contributed to higher rates of microbiologically confirmed infections in our study,” the authors explained.

The team said that the study found high antibiotic prescribing rates, despite low rates of respiratory cultures and confirmed microbiologic infections.

Based on the study findings, the team recommends increased antibiotic stewardship practices in COVID-19 patients.

“These findings are similar to the results of previous studies, suggesting the need for strategies to help clinicians judiciously prescribe antibiotics in patients with COVID-19,” the researchers wrote in the paper.

Further, the team said that more studies are also needed to determine the impact of antimicrobial stewardship initiatives in patients with COVID-19 and assess if antibiotic prescribing practices have changed with increasing information related to bacterial co-infection that was not available early in the pandemic.

Antibiotic resistance on the rise

Apart from the coronavirus pandemic the world is battling today, antibiotic resistance is a long-standing predicament. It has affected millions of people worldwide, and doctors are worried about its long-term effects.

The World Health Organization (WHO) states that antibiotic resistance happens when bacteria change in response to the use of antibiotics. As a result, they become resistant to antibiotics, making them harder to treat.

A growing list of infections, such as pneumonia, blood poisoning, tuberculosis, foodborne diseases, and gonorrhea is becoming more difficult, and sometimes, impossible to treat since antibiotics become less effective.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Source:

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Martin, A., Pillinger, K., Shulder, S., Quartuccio, K., and Dobrzynski, D. (2020). Risk Factors Associated with Increased Antibiotic Use in COVID-19 Hospitalized Patients. medRxiv. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.10.21.20217117v1

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

Martin, Alysa J., Stephanie Shulder, David Dobrzynski, Katelyn Quartuccio, and Kelly E. Pillinger. 2021. “Antibiotic Use and Associated Risk Factors for Antibiotic Prescribing in COVID-19 Hospitalized Patients.” Journal of Pharmacy Practice, July, 089719002110302. https://doi.org/10.1177/08971900211030248. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/08971900211030248.