A combination of innate differences and diet-induced changes to the reward system may predispose some mice to overeat, according to research recently published in JNeurosci.

Food is fuel, but the rising levels of sugar and fat in modern diets make the brain treat it as a reward. One brain region called the ventral pallidum (VP) serves as a hub between reward areas and the hypothalamus, a region involved in feeding behavior. Intertwining food and reward can lead to overeating and may be a contributing factor to diet-induced obesity.

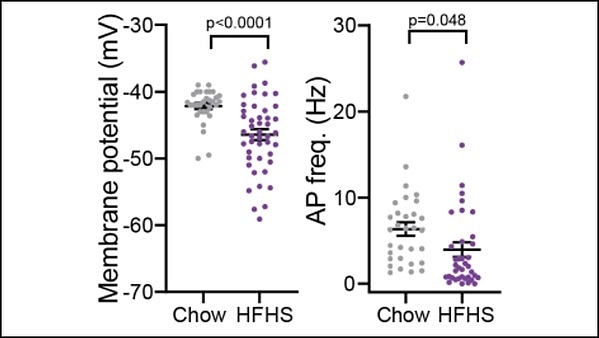

Gendelis, Inbar, et al. measured electrical activity in the VP of mice with unlimited access to high fat, high sugar food for several months. Eating the unhealthy diet changed the electrical properties of VP neurons: the membrane voltage and firing rate decreased, making it harder for neurons to send messages to each other. The change was more pronounced in the mice that gained the most weight. The same set of electrical bursts strengthened synapses in weight gainers but weakened them in mice that gained the least weight. These signaling differences may be innate and not caused by the unhealthy diet itself: the same plasticity differences appear between mice with natural high and low food-seeking behavior even without exposure to an unhealthy diet.

Source:

Journal reference:

Gendelis, S., et al. (2020) Metaplasticity in the ventral pallidum as a potential marker for the propensity to gain weight in chronic high-calorie diet. JNeurosci. doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1809-20.2020.