An international team of researchers from Spain, the United States, Brazil, Argentina, France, Australia and Chile has assessed risks posed by the ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on Antarctica wildlife. Their study has now been published in the latest issue of the journal Science of the Total Environment.

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) that causes COVID-19 has led to the infection of over 52.1 million people worldwide. In light of resurgent cases, many countries have attempted to stop the spread of this highly infectious virus by breaking the transmission chain with restrictive measures and second lockdowns – as in the case of Belgium, Italy and the United Kingdom. The virus and its knock-on effects have taken a severe toll on global public health and the economy.

Many believe the virus to have a zoonotic origin, meaning it originated among animals and has since jumped to humans. This also suggests a cross-species transmission of the infection among animals. “All members of the seven identified coronaviruses that infect humans are suspected of having zoonotic origins,” say the researchers. There has also been evidence of “reverse zoonosis” wherein the infection is transmitted from humans to animals.

Antarctica

Before March 2020, Antarctica was the only continent untouched by SARS-CoV-2. However, there are now concerns about the virus’ potential to spread throughout the region, after at least one COVID-19 positive person was found to have visited several sites along the Antarctic Peninsula during the region’s tourist season in March. The researchers suggest that the potential for humans to transmit the virus to wildlife in Antarctica remains a threat. Thus, they have proposed a series of measures that they believe would limit the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 to Antarctic wildlife.

Cross-species transmission

Several factors determine the potential of SARS-CoV-2 to show cross-species transmission. Among other coronaviruses, evidence suggests that their spread first occurs among animals who often act as reservoirs of this type of infection that then go on spread it to humans. SARS-CoV-2 itself has been found among bats and pangolins and a wide range of vertebrate hosts, including minks, domestic cats and dogs, ferrets and hamsters, among others.

Host susceptibility to the virus is determined by the presence of the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) cell surface receptor, predicted by an in-silico analysis. This analysis shows a low risk of this infection among fish, amphibian, reptile and bird species.

Risk among Antarctic personnel

Until October 2020, there had been no human cases in the Antarctic research station among the nearly 5,000 personnel. Since most of the research work and tourism often take place within close confines, there is a high risk of human to human transmission, wrote the researchers. Early detection and segregation is thus vital, they wrote.

Stability of the virus in the Antarctic environment and transmission risk to wildlife

SARS-CoV-2 is relatively stable in the form of aerosols and can survive on surfaces for up to 72 hours, but temperature and humidity are important for its viability as well as infectivity. SARS-CoV-2’s stability is increased in cold conditions, the team explains. The Antarctic’s environment thus could be very hospitable to the virus and could help facilitate its transmission.

The researchers suggest that the risk of virus introduction and transmission is particularly heightened in areas with higher research work and tourist activities, such as the South Shetland Islands, the northern Antarctic Peninsula and Victoria Land.

The team also says that there has been evidence of viral shedding in the feces of infected persons in the region, which increases the risk of wastewater contamination. This presents a possible source of infection for wildlife and could lead to reverse zoonosis.

Susceptibility of Antarctic wildlife to infection by SARS-CoV-2

The researchers write that the Adélie penguin (Pygoscelis adeliae) and the emperor penguin (Aptenodytes forsteri) have a very low risk of SARS CoV-2 infection, similar to that of other birds. Antarctic pinnipeds also have a low risk of the infection.

There are 14 cetacean species, of which 12 species, including Antarctic minke whale (Balaenoptera bonaerensis), killer whale (Orcinus orca) and sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus), carry a medium to a moderately higher risk of transmission.

Future studies can actually quantify the risk of infection among Antarctic wildlife. Moreover, there is currently a gap in our knowledge regarding the susceptibility of Antarctic wildlife to SARS-CoV-2. In-silico modeling could help us to understand which animals are susceptible to this infection.

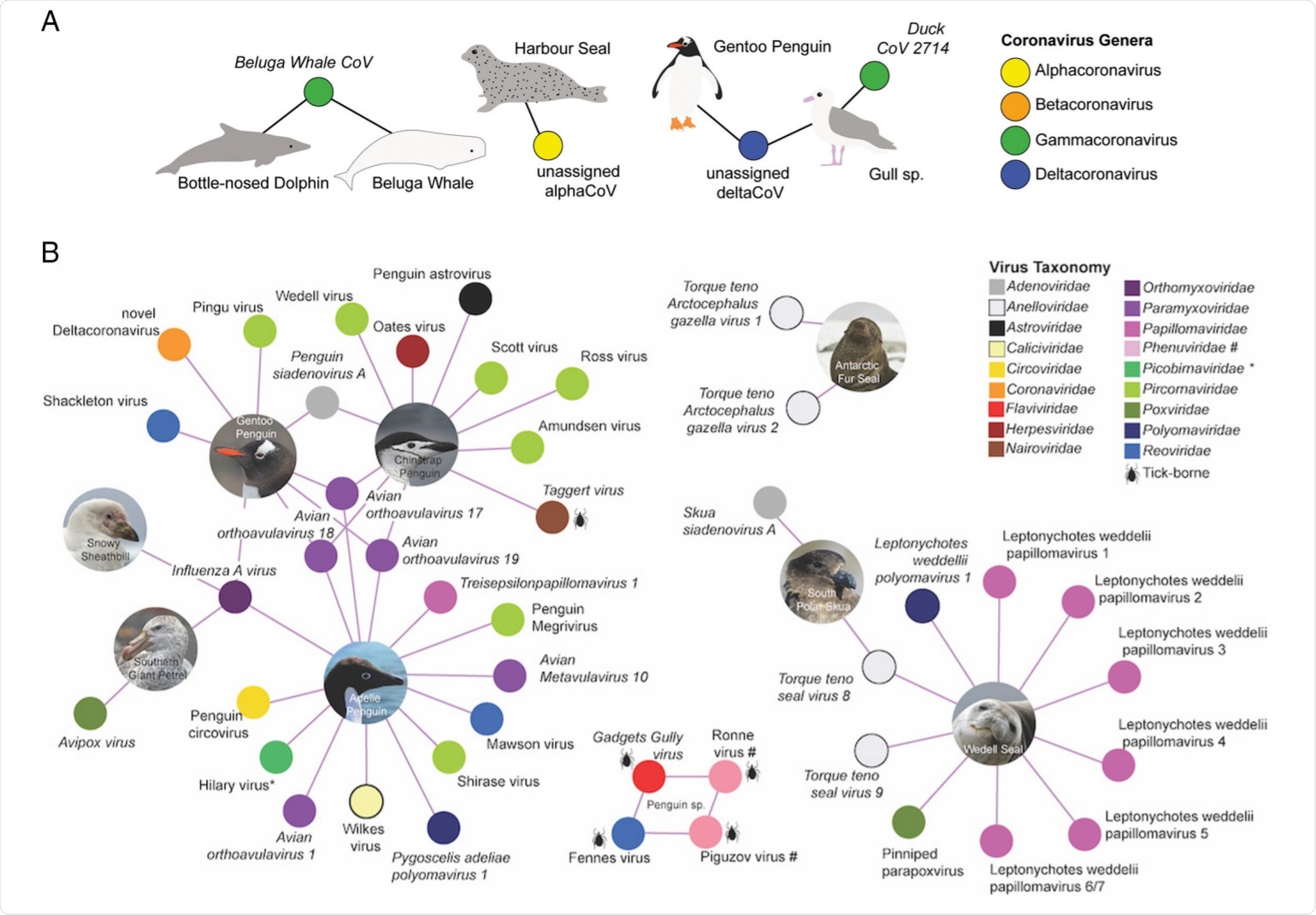

Viral species relevant to this risk assessment. (A) Coronavirus species detected in marine mammals and seabirds, globally. A filled circle refers to a virus, and is coloured according to the genera. Hosts are indicated by an image and connected by lines to the viruses from which they have been detected. A virus (filled circle) is connected to more than one library indicates that the same (putative) virus species has been found in both hosts. Ratified viral species are presented in italics, putative viral species are presented in regular text. Silhouettes generated by M. Wille. (B) Viral species detected in Antarctic birds and mammals. We have not included viral species detected by serology. Only viral species detected in Antarctica have been included; we have excluded viral species recorded on sub-antarctic islands such as South Georgia Island and Macquarie Island. A filled circle refers to a virus. Hosts are indicated by an image and connected by lines to the viruses from which they have been detected. Ratified viral species are presented in italics, putative viral species are presented in regular text. Viruses transmitted by ticks are indicated by a tick silhouette. Picobirnaviridae, indicated by an asterisk have previously been associated with vertebrate hosts. Other than Taggert Virus, in which viral reads were found in Chinstrap Penguins, the Antarctic hosts of tick viruses are not confirmed. Gadgets Gully virus has been detected in ticks in Antarctica and King Penguins in Macquarie Island. Ronne Virus and Piguzov virus, members of the Phenuvidiae are indicated with a # and their avian hosts have not been confirmed despite being detected in ticks adjacent to penguin colonies in two independent studies. All images were taken by M. Wille.

Preventative measures for researchers and tourists reduce viral spread

The researchers recommend a range of measures that could help prevent SARS-CoV-2’s spread among Antarctic wildlife, with a focus on research and tourist activities on the continent:

- For the research facilities staff (crew, scientific and technical personnel):

- Getting tested for SARS-CoV-2 before entering Antarctica and following quarantine procedures for two weeks.

- Self-isolation for those with symptoms should, including no contact with humans or animals.

- Practicing caution while handling animals.

- Disinfecting clothing prior to and after working with animals.

- Disinfecting field equipment.

- Preventing inadvertent exposure of wild animals to unattended field equipment.

- Maintaining personal hygiene.

- Limiting movements, unless absolutely essential.

- For tourists (including visiting research staff):

- Getting tested for SARS-CoV-2 before entering Antarctica and following quarantine procedures for two weeks.

- Self-isolation for those with symptoms should, including no contact with humans or animals.

- Those in contact with an infected person in a vessel need to self-isolate and must be prevented from coming in contact with wildlife.

- Maintaining a minimum distance of 5 m or greater from wildlife.

- Preventing exposure to wildlife and field equipment.

- Not to sit or lie on bare ground or rocks.

- Maintaining personal hygiene.

- Additional recommendations:

- Surveilling wastewater from cruise ships, research stations and research vessels for the presence of SARS-CoV-2