As the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic continues to take a heavy toll on life and health, it is vital to know if the development of neutralizing antibodies in those who have recovered from the infection is associated with protection against reinfection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

At present, there are only scattered reports of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection, and these have been observed to occur mostly in patients who recovered from mild or asymptomatic primary infection. This suggests that infection confers antibody-mediated protection against reinfection, even though the availability of PCR testing was limited early on. No report on the longitudinal rates of infection in seropositive vs seronegative individuals has been reported so far.

The current study shows the results of assessing seropositivity and the incidence of symptomatic reinfection in a large group of healthcare workers (HCWs), followed up over a median of 188 days following a negative serology and 127 days after a positive serology test. Of this group of over 12,200 who had anti-spike IgG measured, about 11,000 were seronegative and ~1,250 seropositive. Of the latter, about 80 were found to seroconvert during the follow-up period.

Symptomatic patients who underwent PCR testing made up similar proportions of both seronegative and seropositive HCWs. Asymptomatic screening was carried out more often among seronegative HCWs than seropositive HCWs, at 138 tests/10,000 person-days vs. 102 tests/10,000 person-days.

In this group, among the seronegative, there were ~90 cases of symptomatic COVID-19 confirmed by real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT PCR), or 0.46/10,000 days at risk (the at-risk period begins at 60 days after the positive serology test). There were another 76 asymptomatic PCR positives, at 0.40/10,000 days at risk.

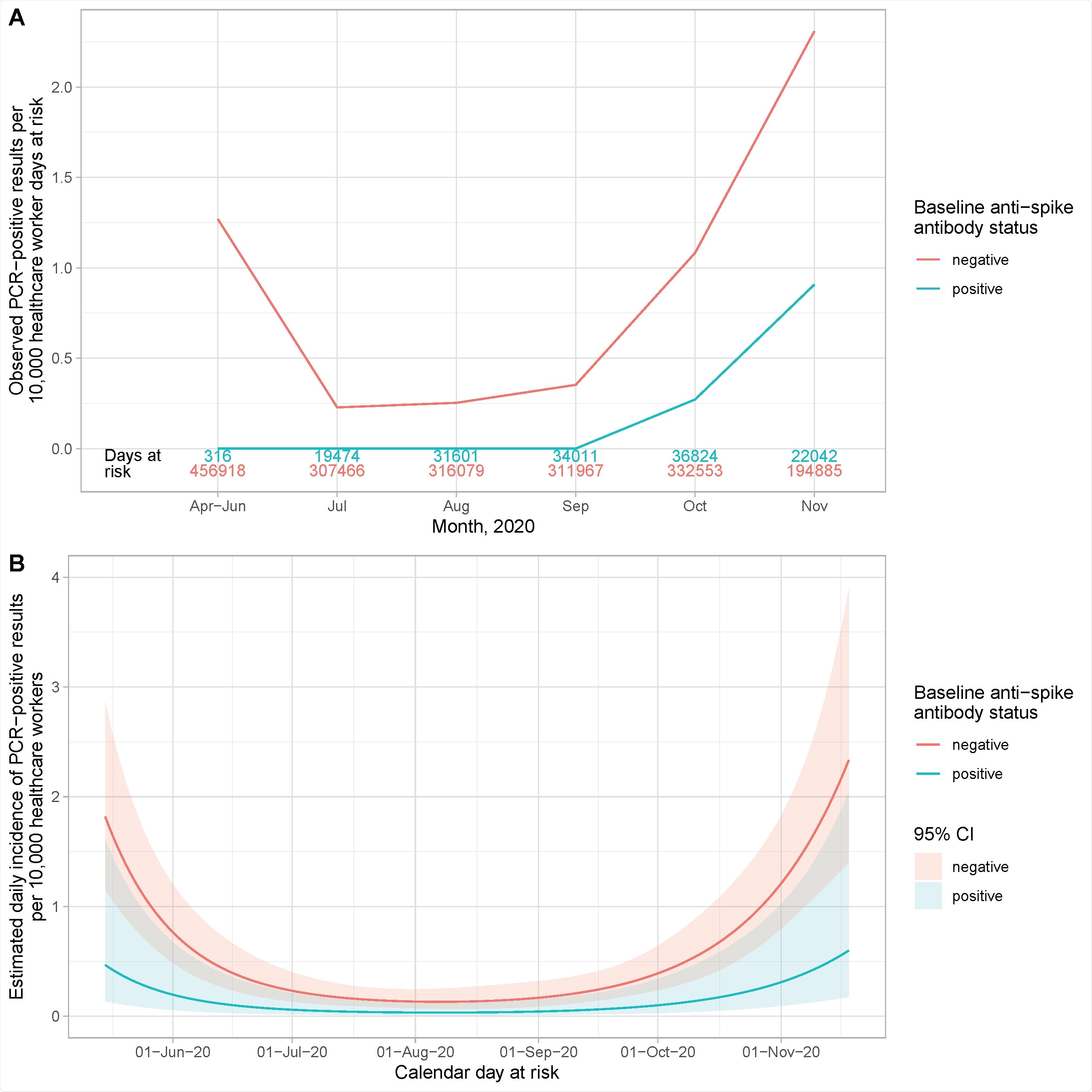

Observed and estimated incidence of SARS-CoV-2 positive PCR results by baseline anti-spike IgG antibody status. Panel A shows the observed cases per 10,000 HCW days at risk. The cases in seronegative staff are shown in red and seropositive staff in blue. The total number of HCW days at risk by month are shown in red and blue text above the x axis. Panel B shows the estimated daily incidence of SARS-CoV-2 positive PCR results per 10,000 HCW days at risk, by baseline antibody status (95% confidence intervals are indicated by the coloured ribbons). The Poisson regression model is adjusted for age (using a 5 knot spline, similar to Supplementary Figure S2), gender and calendar time fitted as continuous, using a 5 knot natural cubic spline with default knot positions.

Among those with anti-spike antibodies, the number of symptomatic infections was zero. There were only 3 asymptomatic cases among the seropositive individuals, or 0.21/10,000 days at risk. Thus, there were lower PCR positivity rates overall among the seropositive. The ratio of the incidence rates for new PCR positive cases among seronegative individuals was, therefore, only a quarter of that among seropositive HCWs (Incidence rate ratio 0.24).

There was no significant difference in the incidence rate ratios, whether antibodies against anti-nucleocapsid IgG alone were considered or combined with antibodies against the spike antigen. Seronegative had a PCR positive rate of 0.88/10,000 person-days compared to 0.21/10,000 person-days among seropositive individuals.

Among the three seropositive individuals with anti-spike antibodies, who were tested PCR-positive, one first had symptomatic COVID-19 in April, seroconverted subsequently, and remained seropositive until October, with five negative PCR tests. On day 190, the patient again tested PCR positive, without any symptoms, and then tested PCR negative 2 and 4 days later.

Another HCW had a history of fever in February, was not tested by PCR, but was subsequently found to be seropositive for the anti-spike antibody. Anti-nucleocapsid antibodies were not detected. This patient then became seronegative from July through October, on three separate occasions, with anti-spike antibody titers dropping while anti-nucleocapsid antibody remained low. There were then 14 negative PCRs before an asymptomatic positive PCR at 180 days from the first antibody test. The patient had a history of transient muscle pain after an influenza vaccine two days prior to the positive PCR test.

Similar was the case of the third HCW who had fever and anosmia but was not tested by PCR. In May, the patient had both anti-spike and anti-nucleocapsid antibodies. The PCR positivity came after 230 days from the earliest symptoms, but there were no symptoms at that time.

Even though the incidence of PCR positive cases was higher in the first and second waves of the pandemic, seronegative individuals always had higher incidence rates than seropositive. Secondly, the higher the baseline anti-spike antibody titer, the lower the subsequent positive PCR test rate. Some individuals had low baseline titers, either because they were tested in the declining phase or because they had low peak antibody titers throughout.

The findings suggest that prior infection with SARS-CoV-2 producing antibodies against the nucleocapsid or spike antigens offered protective immunity against reinfection for most people for at least 6 months subsequently. Further studies will be necessary to evaluate the duration of such immunity and the characteristics of such protection. In the absence of such knowledge, even those HCWs who have been infected should continue to practice social distancing and other infection control measures as usual.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources