Researchers in the United States have conducted a modeling study suggesting that severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) – the agent that causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) – could have been circulating in the Chinese province of Hubei as early as mid-October 2019.

The team – from the University of Arizona and the University of California San Diego – say the models calculated that the virus was probably circulating at low levels in Hubei during early November and possibly in mid-October at the very earliest.

The study also suggests that more than two-thirds of zoonotic infections (those spread from animals to humans) would have been quick to die out, making it difficult to establish when SARS-CoV-2 started spreading between humans once it had jumped from animals.

“Our findings highlight the shortcomings of zoonosis surveillance approaches for detecting highly contagious pathogens with moderate mortality rates,” says Joel Wertheim (University of California San Diego) and colleagues.

A pre-print version of the paper is available on the bioRxiv* server, while the article undergoes peer review.

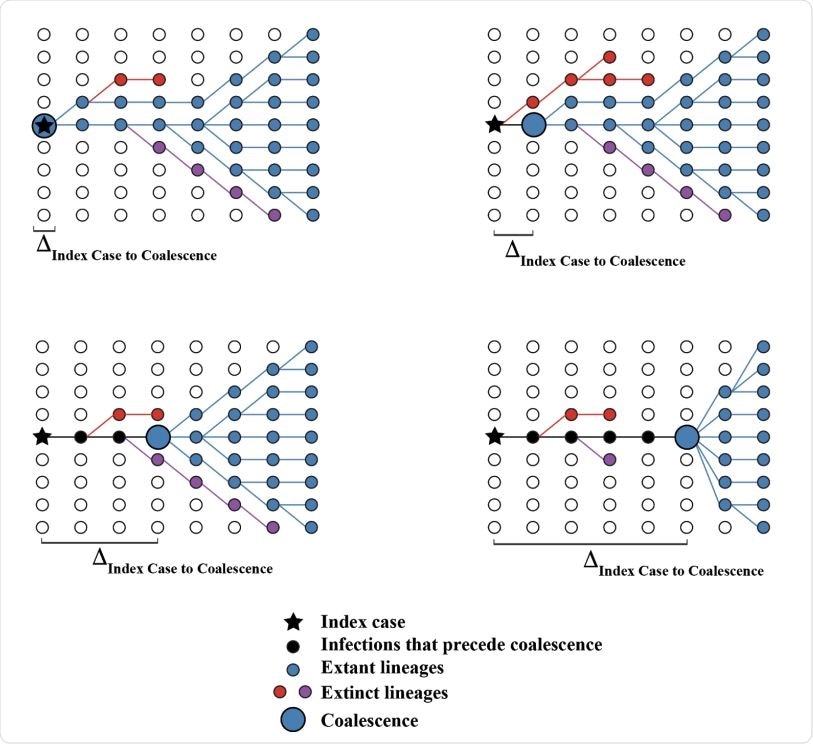

Hypothetical coalescent scenarios depicting how the time between index case infection and time of stable coalescence can vary based on stochastic extinction events of basal viral lineages. Coalescence can occur within the index case (upper left) or in cases infected later in the course of the epidemic. In extreme cases, the epidemic can persist at low levels for a long time before coalescence (lower right).

“Understanding when SARS-CoV-2 emerged is critical”

Since the COVID-19 outbreak was first identified in Wuhan, Hubei, late last year (2019), significant efforts have been made to understand when SARS-CoV-2 started spreading between humans.

“Understanding when SARS-CoV-2 emerged is critical to evaluating our current approach to monitoring novel zoonotic pathogens and understanding the failure of early containment and mitigation efforts for COVID-19,” writes the team.

Both epidemiological and phylogenetic approaches have suggested the outbreak was linked to The Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan in late December of last year, but COVID-19 cases from early December lacked connections to the market, say the researchers.

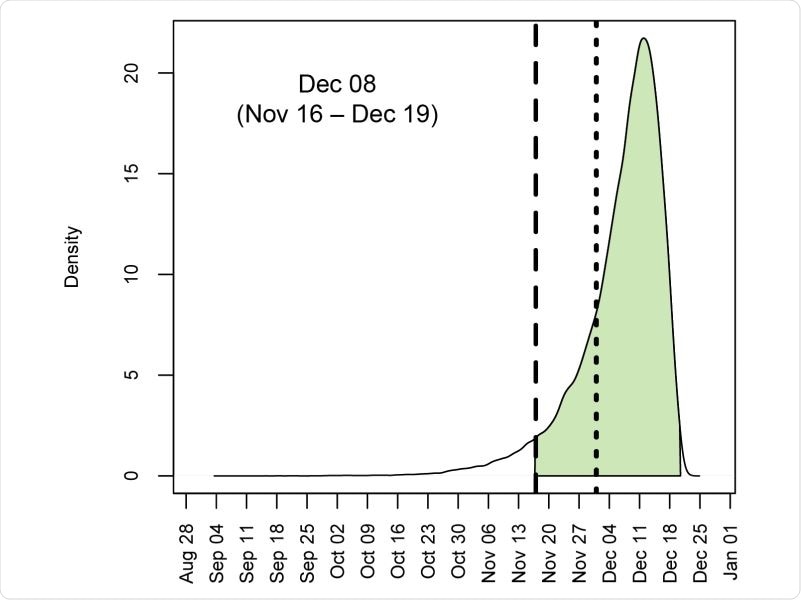

Posterior distribution for the time of the most recent common ancestor (tMRCA) of 583 sampled SARS-CoV-2 genomes circulating in China between December 2019 and April 2020. Shaded area denotes 95% HPD. Long-dashed line is 17 November 2019, and short-dashed line is 01 December 2019.

Molecular clock phylogenetic analyses have suggested that the time of the most recent common ancestor (tMRCA) dates back to late November or early December 2019 and possibly as far back as October.

“Crucially, though, this tMRCA is not necessarily equivalent to the date of zoonosis or index case infection, because coalescent processes can prune basal viral lineages before they have the opportunity to be sampled, potentially pushing SARS-CoV-2 tMRCA estimates forward in time from the index case by days, weeks, or months,” explain Wertheim and colleagues.

What did the researchers do?

The team used a coalescent framework to combine a retrospective molecular clock analysis with forwards epidemiological simulations to estimate the timing of the SARS-CoV-2 index case in Hubei province.

The analysis identified that the plausible time interval for when the first SARS-CoV-2 case may have emerged was the period between mid-October and mid-November.

The researchers point out that studies conducted since the outbreak have demonstrated the outsized contribution of superspreading events to SARS-CoV-2 propagation – where the average infected individual does not spread the virus.

By characterizing the likely dynamics of the virus prior to its discovery, the team showed that similar events probably influenced the establishment of SARS-CoV-2 in humans.

Only 29.7% of the epidemics the team simulated went on to become self-sustained epidemics. The remaining 70.3% were self-limiting and went extinct before they could have triggered a pandemic.

“The successful establishment of SARS-CoV-2 post-zoonosis was far from certain, as more than two-thirds of simulated epidemics quickly went extinct,” writes the team.

It is “highly likely” that the virus was circulating in early November

It is highly likely that the virus was circulating at low levels in Hubei province during early-November 2019 and even as early as mid-October 2019, say Wertheim and colleagues.

“However, the inferred prevalence was too low to permit its discovery and characterization for weeks or months,” they add.

The researchers say the results highlight the unpredictable dynamics that characterized the earliest days of the pandemic.

By the time the virus had been identified, it had already firmly established itself in Wuhan. This is a pattern that could have played out across the globe, given that the virus was repeatedly introduced but only occasionally took hold, says the team.

“This brief period of time suggests that this pandemic, like potential future ones with similar characteristics, permitted only a narrow window for preemptive intervention,” write the researchers.

Wertheim and the team say their findings show that claims suggesting SARS-CoV-2 was present in sewage systems outside of China before November and that international spread occurred around late November or early December should be viewed with skepticism.

Testing wastewater may be the best approach

However, the virus may be detectable in wastewater from Hubei province, should archived samples for early-to-mid November 2019 exist, they add.

“This approach may present the best chance of early detection of future, similar pandemics during the early phase of spread where we estimate very low numbers of infections,” advises the team.

Identifying the animal reservoir or potential intermediate host of SARS-CoV-2 could also help determine the period, location, and circumstances surrounding the original infection in humans.

However, in the meantime, coalescent-based approaches allow researchers to look back beyond the tMRCA, towards the earliest days of the pandemic, say the researchers

“Although there was a pre-tMRCA fuse to the COVID-19 pandemic, it was almost certainly very short,” they conclude.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources