Researchers in the United Kingdom have set up a “living” systematic review in response to the rapidly emerging evidence-base for “long COVID” – the term used to refer to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) symptoms that persist for longer than would usually be expected.

Some people who develop COVID-19 experience symptoms that persist for weeks or even months beyond the two to six weeks it typically takes for people to recover. These individuals sometimes develop medical complications that may have long-lasting health effects.

However, “a precise case definition of long COVID is problematic because, currently, there is little consensus on the exact range, prevalence, and duration of symptoms in post-acute COVID-19,” says Charitini Stavropoulou from the University of London and colleagues.

Now, the team has set up a “living” systematic review that seeks to capture evidence on the frequency, profile, and duration of persistent COVID-19 symptoms and to continually update this evidence-base as new research emerges. Updates may be made for up to two years from the date of the original publication presented here.

This initial version provides a comprehensive summary of the evidence currently published, which, so far, is of limited quality and vulnerable to bias, say the authors.

The current evidence reflects a lack of control groups, inconsistent data collection methods, and poor external validity, says the team. Furthermore, few studies were conducted in the primary care setting, no studies were focused on children, and no studies were conducted in low- and middle-income countries.

Stavropoulou and colleagues identify areas where further research is urgently needed, starting with the need for robust, controlled, prospective cohort studies, covering different settings and population subgroups, with data collected and recorded in a standardized way.

A pre-print version of the paper is available on the medRxiv* server while the article undergoes peer review.

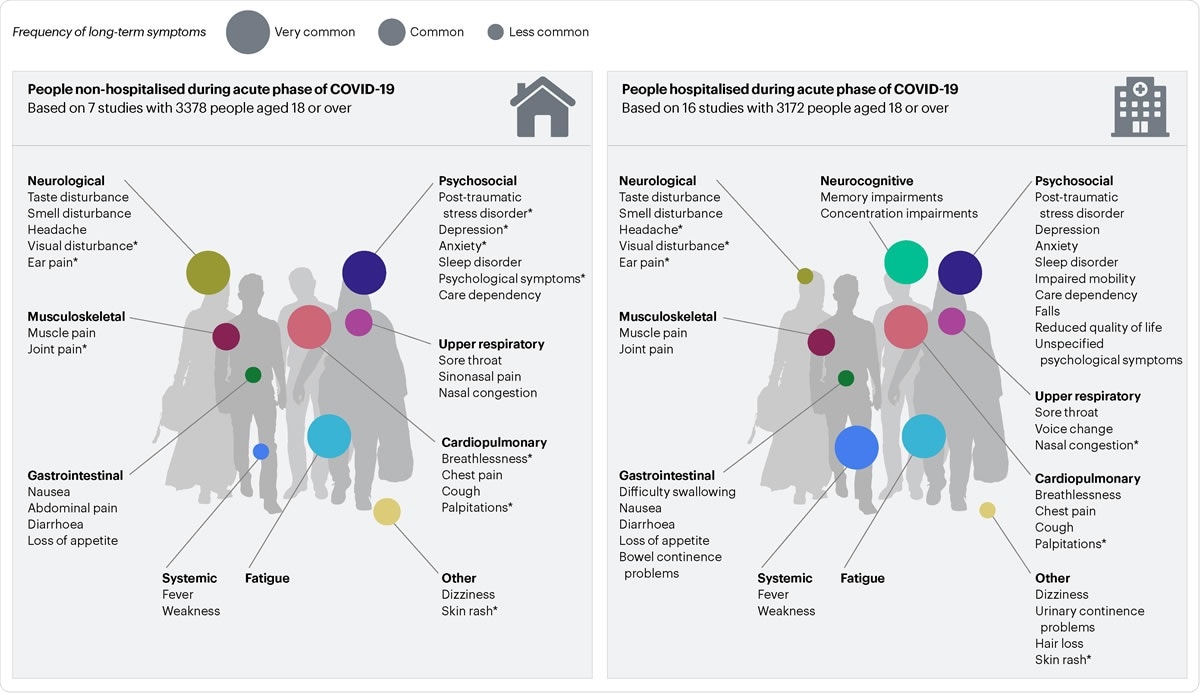

Long Covid symptoms

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

What did the researchers do?

The team of researchers from the University of London, University of Oxford, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, University of Bristol, Long Covid Support and Queen Elizabeth Hospital searched Medline and CINAHL (EBSCO), Global Health (Ovid), WHO Global Research Database on COVID-19, LitCOVID, and Google Scholar up to the 28th September 2020 for studies reporting on long-term symptoms and complications among people with confirmed or suspected COVID-19.

The team only selected studies that included more than 100 participants and reported outcomes from 21 days following onset of COVID-19 symptoms or at any time post-hospital discharge. Studies investigating both hospitalized and non-hospitalized individuals were included.

The researchers identified 1,553 studies, of which 100 met the inclusion criteria. Of these, 28 studies qualified for data extraction and risk of bias assessment. Sixteen of the studies were cohort studies; ten were cross-sectional and two were case series.

Overall, the analysis covered 9,442 individuals (aged 18 years or older) from 13 countries and the longest mean follow-up period was 111 days from hospital discharge.

What did the study find?

The diverse range of persistent symptoms reported, including systemic, cardiopulmonary, gastrointestinal, neurological, and psychosocial, across both hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients suggest a complex and heterogenous condition, says Stavropoulou and colleagues.

“It is currently unclear whether that heterogeneity is a true effect or generated by the varied methods by which it has been studied,” they write.

The quality of the evidence-base for the clinical spectrum of “long COVID” was low and vulnerable to bias.

Few studies were designed as prevalence studies and symptoms were generally only reported by a small number of participants, without control groups, thereby limiting the ability to establish causality.

For example, psychosocial symptoms such as anxiety and depression could be related to viral infection or to other factors such as social distancing measures and media reporting. Furthermore, the studies significantly varied in their design, setting, length of follow-up, and approaches to ascertaining symptom data.

The team also found that evidence among certain populations and settings was lacking. For example, data on non-hospitalized patients were limited and no studies focused on children, despite anecdotal evidence suggesting that long-term COVID-19 symptoms also affect pediatric populations.

Furthermore, most (17) of the studies were set in Europe; six were set in Asia; two in North America, one in South America, and one in the Middle East. None of the studies were set in a low-middle income country.

The studies also demonstrated limited external validity, says Stavropoulou and colleagues

The findings have identified research gaps

The researchers say the findings have identified several research gaps that should help to inform future research priorities.

For example, “the available data do not allow a direct attribution of multifactorial symptoms solely to COVID-19,” says the team. “Larger prospective studies with matched control groups are needed to clearly establish causal links.”

Validated COVID-19 research tools are also needed to standardize data collection and reduce variability in reporting.

“There is a clear need for robust, controlled, prospective cohort studies, including different at-risk populations and settings, incorporating appropriate investigations, collected and recorded in a standardized way.”

The researchers add that since this publication is a living systematic review, future updates will be made as new themes emerge. Search terms and inclusion criteria will also be updated in line with new evidence, research priorities and policy needs.

“The LSR [living systematic review] will be updated periodically… in order to provide relevant up to date information for clinicians, patients, researchers, policymakers, and health-service commissioners,” they write. “Version changes will be identified, and previous reports will be archived.”

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources