Researchers in the UK and the United States have conducted a study demonstrating the significant impact that contact tracing has on the evolution of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

Thiemo Fetzer from the University of Warwick and Thomas Graeber from Harvard Business School say that despite the many challenges faced in contact tracing, this non-pharmaceutical intervention has a significant effect on the progression of the pandemic.

The team assessed the effectiveness of contact tracing within the context of a data processing error that occurred in the UK contact tracing system earlier this year (2020).

The findings suggest that subsequent delays in the referral of confirmed cases to contact tracing has likely propelled the spread of COVID-19 in England.

The researchers say their most conservative estimates suggest that failure of timely contact tracing as a result of the error was directly associated with more than 125,000 additional infections and more than 1,500 additional COVID-19-related deaths.

“We document robust and quantitatively large effects of contact tracing on the evolution of the pandemic,” writes the team.

A pre-print version of the paper is available on the medRxiv* server, while the article undergoes peer review.

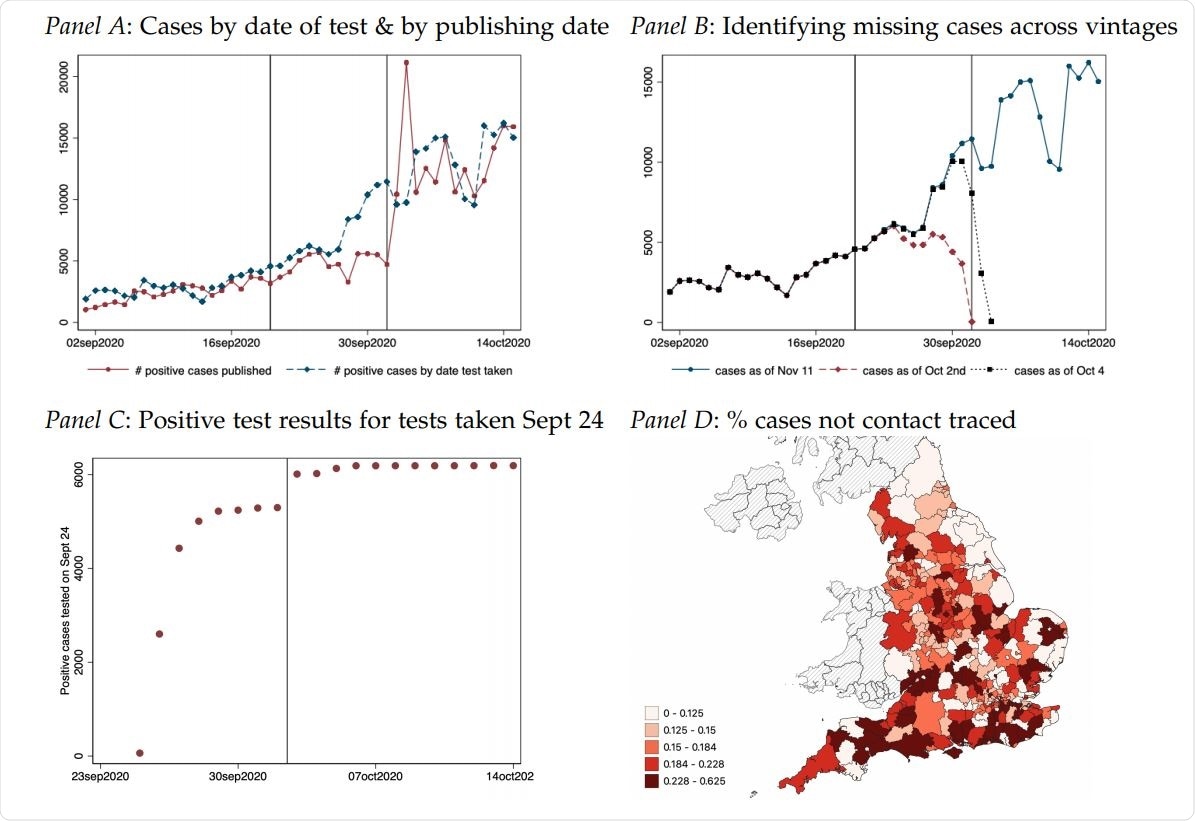

Panel A plots the number of positive cases based on the date that case results are published as well as the number of positive cases based on the date that the test was taken (not when the result was made public). There is a notable divergence between positive results published and positive test results from Sept 20 to Oct 2 capturing the delayed referral of positive cases to contact tracing. Panel B documents the number of cases by date on which a test was taken for three different versions of the dataset: Nov 11, Oct 4 and Oct 2nd. The data for Oct 4 includes a large set of the missing positive cases that were not reported in the Oct 2 data version resulting in large upward revisions. These revisions capture cases that were not referred to contact tracing until Oct 3 or 4th the earliest. Panel C illustrates this using data for all tests taken on Sept 24. Over time the reported value of positive COVID-19 cases converges to the true value as all test results get processed. Usually, 5 days after a test is taken at least 95% of all test results have been published. Between October 2 and October 3 the case count for Sept 24 jumps by around 715 cases or 12% of all cases due to the Excel glitch. Panel D illustrates the geographic distribution of the fraction of cases tested from Sept 20 to Sept 27 that were not referred to contact tracing until Oct 3 or Oct 4.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Effective contact tracing is challenging to implement

Contact tracing systems have been of paramount importance in the public health response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The relative success some countries have had in controlling the pandemic has repeatedly been attributed to the effectiveness of contact tracing systems.

Contact tracing involves contacting people who have tested positive for infection and asking them to submit information on their recent, close contacts. Contact tracers then attempt to get in touch with each of the contacts and encourage them to self-isolate for a certain period of time.

However, contact tracing systems are challenging to implement and concerns have emerged regarding their effectiveness. Successful implementation relies on contact tracers skills, who are often recruited at short notice and may not be adequately trained.

Furthermore, even when contact tracing is successfully implemented, it can still fail if the system does not elicit the intended behavioral responses.

For example, infected people may be unwilling to provide tracers with accurate information about their contacts, possibly because they distrust the process, are afraid of scams or have other privacy and security concerns.

“An even more pressing problem is that contacts may not believe contact tracers. This can lead to non-adherence to self-isolation, undermining the very purpose of contact tracing,” writes the team.

However, the effectiveness of contact tracing is notoriously difficult to assess due to a lack of naturally occurring, exogenous variation, say the researchers. The existing literature is, therefore, mainly based on correlational evidence.

Correlational evidence is subject to the concern that variation in the level of contact tracing across time or geographical areas is correlated with other variations unrelated to contact tracing, such as changes in other public health measures or local populations differing in their adherence to self-isolation.

What did the researchers do?

The researchers exploited a unique quasi-experiment in England that generated variation in the intensity of COVID-19 contact tracing.

On October 3rd, UK authorities announced that due to a data processing error involving an Excel spreadsheet, 15,841 cases of COVID-19 were not immediately referred to the contact tracing system between September 25th and October 2nd.

“Different areas in England were affected to very different degrees by the late referrals to contact tracing originating in the data glitch, providing our source of exogenous variation to determine the effectiveness of contact tracing,” explains the team.

The researchers conducted a series of analyses to test their assumption that the subsequent local affectedness was not related to any other factors that determined the previous spread of COVID-19.

What did they find?

The analyses confirmed that the local impact of the data error was unrelated to a wide range of area characteristics such as demographic makeup and recent trends in exposure to COVID-19.

Areas that were more affected by the missed referrals experienced a drastic increase in the number of new cases, COVID-19 related deaths and the number of people testing positive. The authors attribute these outcomes to the effect the missed referrals had on the pandemic’s growth.

There was also a higher number of cases in the aftermath of the data correction, suggesting a decline in the performance of the contact tracing system.

Strong evidence for the effectiveness of contact tracing

The researchers estimated that the specific failure of timely contact tracing following the data glitch was associated with somewhere between 126,836 and 185,188 additional cases and between 1,521 and 2,049 additional COVID-19-related deaths.

“Our findings provide strong quasi-experimental evidence for the effectiveness of contact tracing,” they write.

“In the context under consideration, the non-timely referral to contact tracing due to a data blunder has likely propelled England to a different stage of COVID-19 spread at the onset of a second pandemic wave,” concludes the team.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources